ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Picasso at The Met, in retrospect

By KATRINA STUART SANTIAGO

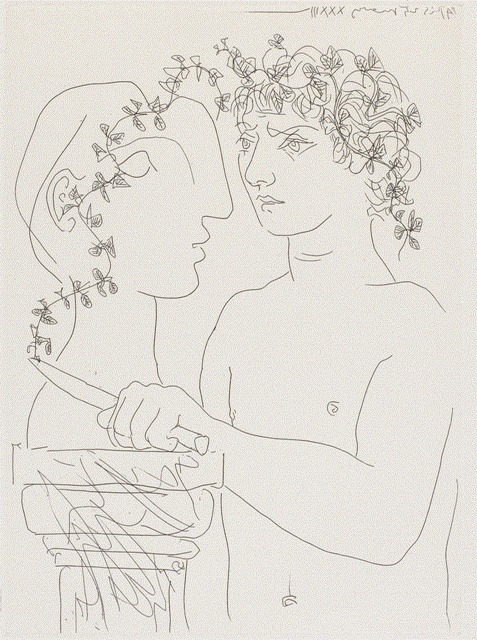

Pablo Picasso Joven escultor trabajando, 25 marzo 1933 FUNDACION MAPFRE’s Collections © Sucesión Pablo Picasso. VEGAP. Madrid, 2011 (Young Sculptor at Work)

It was with discomfort that I listened to the speeches that would close the Pablo Picasso exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum: they were thanking members of the media who had helped create a buzz around the exhibit after all. I had kept putting off the trip to The Metropolitan Museum for it, even as I insisted that others see it. In fact, there was a conscious refusal to see Picasso, because seeing it would make me want to write about it which, I always feel, is time and space that might be used to talk about local art and culture – and there were plenty of those happening at around the same time that the “Suite Vollard," an exhibit of the artist's copper etchings, opened.

Not surprisingly, the Met had a record number of visitors in the span of time that the Picasso exhibit was up, a measure of an exhibit-going, not necessarily art buying, market. But too it is a measure of how our museums can hold world class exhibits – the kinds that happen elsewhere in Asia, too, something we should be able to take pride in. Though it might do the Met well to be open on Sundays and have the same schedule as the National Museum, if only to encourage more of us to make the trip to Manila museums instead of going to the malls.

Having admitted to a snub of sorts, borne of nothing but the arguable notion of priorities, on its last days I would go to The Met twice to see “Suite Vollard,” which should not be misconstrued as a measure of my regret. In fact if anything, it should be a measure only of its value as an international exhibit.

Along with the promise of some music from Master Cellist Renato Lucas, and the drama of a farewell to Picasso, the by-invitation-only closing ceremony gathered less of a crowd than expected. But the point would still be the exhibit, set against red walls, the drama only heightened by what seemed to be excitement – if not giddiness – in the air. To say goodbye to Picasso means the possibility of having him back.

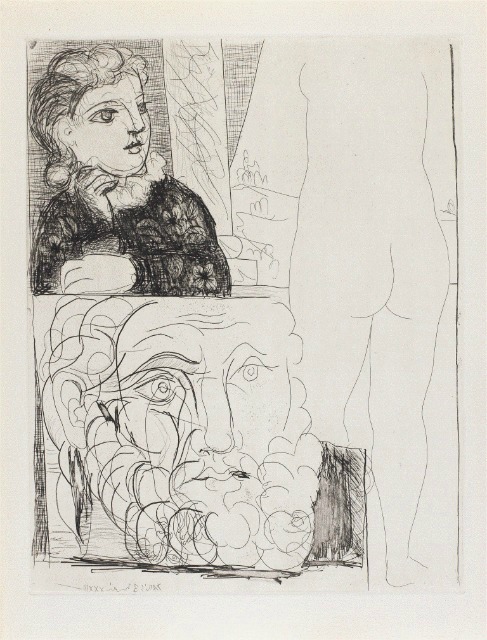

Pablo Picasso Mujer acodada, escultura de espaldas y cabeza barbuda, 3 mayo 1933 FUNDACION MAPFRE’s Collections © Sucesión Pablo Picasso. VEGAP. Madrid, 2011 (Woman Leaning on Her Elbow, Sculpture Viewed from Behind and Bearded Head)

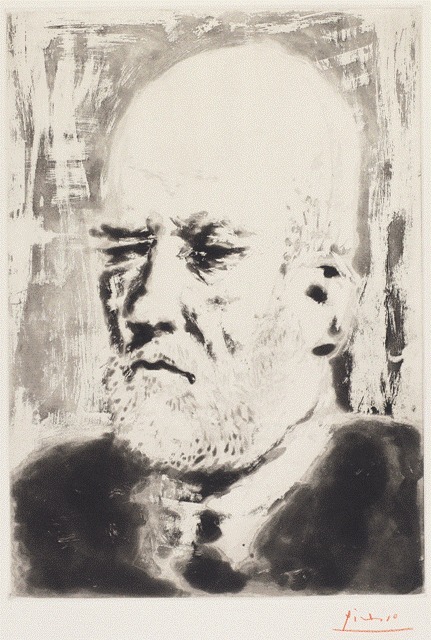

There is reason for the optimism. The “Suite Vollard” may not be as famous as Picasso’s cubist work, or those now labeled part of his Blue or Rose periods, but that is precisely why it is extraordinary work. Let go of preconceived notions of what a Picasso work must look like, let go even of its consideration as his tribute to classicism, and what you have is an aesthetic that is nothing but black on white, in etchings and aquatint and drypoint. From afar and collectively, it seems more bare than you’d expect. Of course up close the brilliance is in the details, the differences among repeated images about the minor shifts in perspective, the addition of one thing, another person, a window in the background, flowers on the windowsill, into the mix.

The introduction to the collection safely falls under “Miscellaneous,” under which the more disparate – therefore more interesting – images fall. Here were images of the circus, of women in contemplation, of women’s bodies being uncovered by fawn in one plate, man in another. Here some of Picasso’s images fall back on cubism as aesthetic, others reveal how Picasso’s sense of the human body is one that has breadth and scope and possibility, where sensuality is in the pose and posture, where sex is necessary undertone.

The 46 plates that make up the “Sculptor’s Studio” requires an amount of patience if the expectation is a grand narrative instead of the simplest of love affairs between artist and model and sculpture (a head, a body, all always familiar). It is said that this was Picasso’s tribute to his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter as his model and inspiration, yet more than the realities upon which this is grounded, what resonates is how the artist appears here, not just as drawn vis-à-vis the model in various poses, but as the artist beyond the canvas, as the one who draws. Here is Picasso’s presence as artist, rendering the model in what could have been an infinite set of poses, only limited by how she might be imagined, how she could be rendered by a hand that is enamored with her. She could do no wrong, be no wrong.

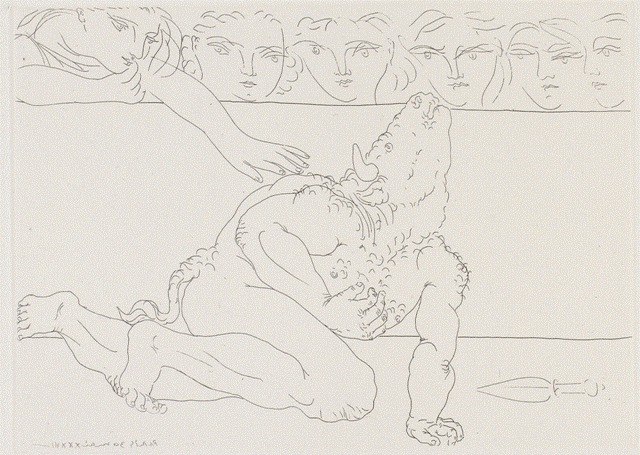

Pablo Picasso Minotauro moribundo, 30 mayo 1933 FUNDACION MAPFRE’s Collections © Sucesión Pablo Picasso. VEGAP. Madrid, 2011 (Dying Minotaur)

But this love affair between artist and model, its overriding calm and quiet countenance, naked bodies and sensual poses notwithstanding, is only made more interesting by the kind of sex and body – monsters and claws – in the etchings that make up the “Minotaur” series. It is said that the artist is turned into Minotaur here, though what seems more crucial is the fact that the Minotaur in place of man is more human than superhuman, more real than supernatural. As such it is the visceral reaction to the images that is destabilized, where the instinctive reaction to monstrosity is jarred by the normalization of its presence with the woman, where the sensual is heightened by the ironic tenderness of monstrous hands, kind eyes, tenderness.

Pablo Picasso Retrato de Vollard II, ca. 1937 FUNDACION MAPFRE’s Collections © Sucesión Pablo Picasso. VEGAP. Madrid, 2011 (Portrait of Vollard II)

It is also this rendering of the visceral as questionable that happens on the level of spectatorship with the series entitled the “Battle of Love” made up of etchings all entitled “Violación” (“Rape”). Here it is the artist’s hand that falls heavier or lighter as it renders the act of sex, presumed to be at its most violent, across a set of five images that look the same. But are different. The lighter strokes allow for the imagination of the act to be more about bodies intertwined, limbs disappearing into one another, the woman’s face neither in agony nor in ecstasy, the man’s posture not necessarily about power. The heavier strokes almost an implosion on paper, of the power struggle that is in the act of sex, where the rape need not be about the woman alone, as it could be about the man, too, body versus body, sex and nothing else.

Here might be Picasso’s gift, in its mere presence in Third-World Philippines in the year 2011. When it happens on the same year that Catholicism rendered the local art scene impotent if not castrated, on the same year that the powers-that-be of arts and culture revealed itself to bow down to fanatic religiosity and conservatism, we can only be also told of how we fail – we fail – at standing up to art and its imagination of life, not as we know it, but as it might be, must be, and actually is.

No matter that we might disagree with this imagining, no matter that it is not according to our own ideals. As Picasso has said, “Art is a lie that makes us realize truth.” And until we are able to go beyond the lie, towards finding that truth, there is not much hope for art where we are. Picasso and the Met’s fab welcome and goodbye notwithstanding. –KG, GMA News

Sources:

“Pablo Picasso: Statement to Marius De Zayas." 1923. Original source: 'Picasso Speaks,' The Arts, New York, May 1923, pp. 315-26; reprinted in Alfred Barr: Picasso, New York 1946, pp. 270-1. Available online: http://www.learn.columbia.edu/monographs/picmon/pdf/art_hum_reading_49.pdf

Suite Vollard Pablo Picasso. Fundacion Mapfre, Fundacion Santiago and the Metropolitan Museum Manila, 2011.

Harding, Eleonor. “The muse and her minotaur: 100 rare Picasso etchings documenting love affair are donated to British Museum.” 29 Nov 2011. Daily Mail online. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2067668/Picasso-prints-100-seen-Pablo-etchings-donated-British-Museum.html

Kinsman, Jane. “Picasso & The Vollard Suite.” The National Gallery of Australia website. http://nga.gov.au/exhibitions/Picasso/index.html

More Videos

Most Popular