ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

The personal stories of EDSA 1986

By LIAN NAMI BUAN, GMA News

People Power is firmly entrenched in our collective consciousness, a singular historical event of almost mythical proportions. But to those who were there, it will always be much more than that: it is a personal memory, a part of who they are and what they have since become.

These are some of their stories.

Fe Tomines, 21 years old at the time, was working at the Manila Peninsula Hotel in Makati. She worked a day at the hotel before putting on her yellow jumper and deciding to take part in the revolution. Joined by friends, she walked the distance from Makati to Ortigas along EDSA to join the hundreds who stood defiantly against the military tanks.

Over at Camp Crame, six-year-old Rhona Albarece sat atop the grill gates overlooking then AFP Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Fidel Ramos and his men. She had come with her family all the way from Bukidnon. She didn't quite understand what was going on, much less the urgency in her parents's voices when they asked her and her sister to spread themselves amongst the crowd.

“Sinabihan kami na maghiwa-hiwalay para kapag may nangyaring patayan, magkakahiwalay kami,” Rhona recounted.

But, fortunately, the family was reunited at the end of the day.

Rhona was just one among thousands of children who witnessed what some are now calling the Philippines’ proudest and greatest moment.

Just four years old at the time, Sherylou Tadeo thought that her whole clan was headed for a family reunion. “Sabi ng mom ko pupunta daw kami sa EDSA para sa amin kasi mahal niya kami,” she told GMA News Online, “hindi ako natakot kasi parang concert, at may mga yellow papers na umuulan at naglalaro lang ako sa paligid.”

Now in her late 20s, she looks back on EDSA 1 as a shining moment in history but doubts that she would allow her two children to participate in such an uprising should it ever happen again.  “Iba noon, we were fighting for freedom then. Ngayon, gagawin na lahat ng politiko makuha lang ang inaasam nila,” she notes.

“Iba noon, we were fighting for freedom then. Ngayon, gagawin na lahat ng politiko makuha lang ang inaasam nila,” she notes.

Romeo Medrano doesn't remember a thing about EDSA '86. He was, after all, just a one-year-old toddler sporting a yellow ribbon on his head, carried aloft by his mother in the crowd.

He knows this because of a faded picture immortalizing that moment, a personal memento which he now proudly keeps close to heart. His brother was there too, in a manner of speaking: Alvin, now 26 years old on the 26th anniversary, considers himself a part of EDSA even if only from the inside of his mother’s womb.

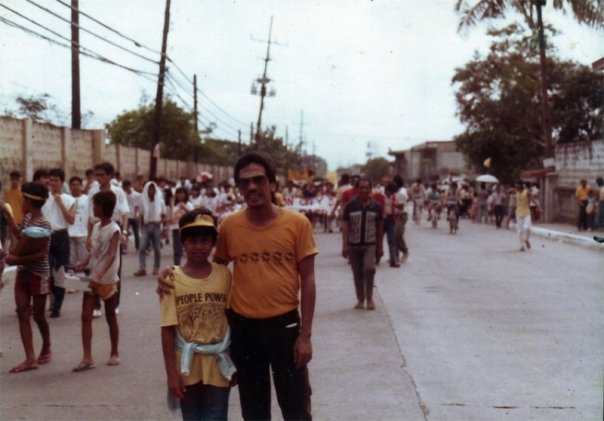

At 13 years old, Alvin Gonda was already into politics. Many years of Martial Law had left a bad taste in his father's mouth, steeling his resolve to see Marcos out of power. And so, father and son threw their full support behind Cory's bid for the presidency.

Alvin told GMA News Online that, as a teen, he was scared at first to join the EDSA rally. But as he walked among the commingled rich and poor, he found family in the company of strangers. He sported a yellow shirt and, with his father and brother, walked through EDSA carrying pro-Cory signs.

Right then and there, he promised to support the Aquino family for always. More than two decades later, he's still true to his promise: he was part of a graphic design team that volunteered for Noynoy Aquino' presidential campaign in 2010.

On the day of the snap elections on February 7, then 18-year-old Peter Paul Mendoza, headed a group called the Bansang Nagkaisa sa Diwa at Layunin (Bandila). Though still just a student at the University of Santo Tomas, he and his group served as watchdogs at the polls. On February 23, as the throng in EDSA reached its peak, he and his friends joined the march. Nothing could weaken their resolve —not even being sprayed with teargas as they approached Santolan.

“Natakot kami ngunit buo ang loob naming maibalik ang demokrasya sa bansa.”

But now, years later, GMA News Online asked him a question he must have heard many times before: Was EDSA worth it?

Peter answers with a flat-out “No.” “Some of the politicians who joined had their vested interests and the economy became erratic,” he told us, “But until now, we're still praying for a rebound.”

Jerome Malic lived around Camp Crame in 1986. He was 19 and an active member of his church, Christ's Commission Fellowship. As threats of violence loom over the impending revolution, his grandparents gave him the go signal to join as “they were relieved that finally, people were courageous enough to stand against dictatorship.” He recalled seeing Enrile and Ramos in person and told GMA News Online, “it was a peaceful revolution, we were very safe and we had fun.”

German Dean Sr., then a member of the Philippine Constabulary, says he was never a rebel soldier. “Nor did I side with Marcos; we were just peacemakers at the time.”

As far as he was concerned, he was just doing his job.

German was scared to be caught in the crossfire, literal or proverbial, but he stood by his duty. Safety had to be ensured and peace maintained, he reasoned. The Constabulary had their work cut out for them. The photo German keeps is one with other members of the Constabulary, grinning for the camera with no trace of violence nor distraught. German is now 53 years old and still serves with the Philippine National Police.

Their stories. Our history.

All these people don't consider themselves catalysts of change, and they certainly don't think of themselves as masterminds of a new tomorrow. Certainly, their names aren't in the history books. But simply being there to witness it all, no matter how big or little the role they played, is a story worth telling in itself.

And today, we tell their stories. Because theirs is a flame that helps keep the fire of EDSA alive. — TJD, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular