ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

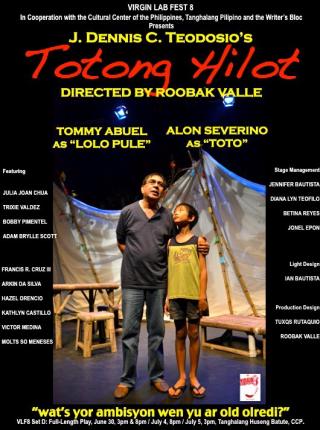

Theater review: The undoing of childhood in 'Totong Hilot'

By KATRINA STUART SANTIAGO

It is provincial Bulacan, it is poverty and children. It is a coming-of-age story. It is a story you’ve seen before.

Except that it isn’t, if only because there are nuances in “Totong Hilot” that force an amount of discomfort in the spectator, for the good and bad of it, if not the too melodramatic for comfort. And then there was, strangely enough, an amount of laughter too, though maybe the production didn’t expect that.

A story of a little boy named Toto (Alon Severino) who insists he wants to be like his Lolo Pule (Tommy Abuel), the town’s resident hilot, it was difficult not to carry a set of expectations about this play, children’s story as it seemed in the beginning. Toto’s tone after all is innocent, his conversations with his playmates even more so, his Lolo comfortably familiar. Along with a stage that was well conceptualized, a set that had its moments, origami hanging on trees, it was everything one would expect of children’s theater.

Tommy Abuel as Lolo Pule demonstrates his healing power after his apo Toto falls from an aratilis tree. GMA News

And then it hits you that this narrative is layered with crisis upon crisis, those that are silenced, those that wreak havoc on family, those premised on the evils of current society. Then you find that it is a painful childhood that’s being written here, where the coming of age is not a matter of the natural usual process, but a fact of being embroiled in discourses larger than what the child can or is expected to handle.

So while it begins with innocent ambitions and naïve dreaming, from Toto and his three friends, the play steadily changes in tone and levels up the complexity. What with the adults in this story, those who are removed from the concerns of their children even as they struggle with poverty and the need to provide for family, and those who are as evil as they come. These the children suffer through without quite knowing it, not until they are at the point of unraveling, if not just ennui.

Totong Hilot is not just a coming-of-age story.

Because there is too much here they do not understand. The folk narratives that surround the inheritance of the power to hilot, the discourse of development and science versus rural poverty and folk healing. The arrival of family from America and its existence as necessary counterpoint to the poverty at home, the deep-seated issues of sisterhood and love that rise to the surface in the midst of need. The neighbor who has lost all hope, the imaginary friend who fights with you, the stranger who promises the world.

It seems to be all too much, but in fact it seems like something “Totong Hilot” should be able to handle and play around with—it felt like something it set itself up for. Which is to say of course that there were some hitches in its telling, ones borne of layering the narrative with more than it needed in the task of staging it.

Using those shadows, for example, barely made sense throughout the story, up until it was used to literally reveal what happens to Toto’s playmates Hiyas and Ning-Ning. Which it didn’t need to tell us really, given the manner in which the uncle was portrayed, given the kind of foreshadowing this already allowed. There was also the fact of the older Toto functioning as both imaginary friend and future, and later narrator. Which might work were he not also the one portraying shifts in setting by, uh, literally lifting parts of this set. Now this wouldn’t be a problem, this wasn’t a problem for the other members of the cast, but that might be because they were actually part of the narrative, and not some imaginary member of it. Then too it might be because the older Toto was moving in and out of the narrative too often, sometimes too swiftly across the stage, and yet he would still have the time and wherewithal to move pieces of the set from one end to another. By the second half of the narrative, the audience could not but laugh at his presence.

Which was a shame because much of the poetry in this story would come from him. You know this from the beginning, but it is revealed the moment you hit the ending and find that the unraveling is his to tell. It’s at this point that you realize, ah, there was a point to his lightness, his seeming calm, from the beginning. His was the gift of foresight, and it all makes sense.

As “Totong Hilot” actually does, hitches notwithstanding. Of course it fell into some clichés, as with the crisis of sisterhood between Lolo Pule’s daughters, or the problem with money in this impoverished context. At the same time you know that what might seem cliché to us is just truth to so many others, and you forgive the story that. Also because it begins and ends, and it tries, to work with aspects of this state of affairs that are new and interesting still.

And then there was also just the acting, the complexities in “Totong Hilot” in the hands of a cast that was competent, both children and adults, alongside a giant such as Abuel. Particularly, Kathlyn Castillo and Hazel Orencio carried the weight of their individual crises and their sisterhood well, even as it could’ve been dealt with more swiftly. Castillo plays the role of the one who went away, the one who wants to be bigger and better this time around, with the right amount of distance and caring it needs. A convention of the balikbayan for sure, but she plays it distinctly without missing a beat.

Toto (Alon Severino) with his dying Lolo Pule (Tommy Abuel), the hilot who inspired Toto's ambition to take after him. GMA News

Francis Cruz III as the older Toto rolls with the punches here, carrying as he does much of that set for most the play. But by the time it ends, this older Toto too is revealed to hold much of what matters in his hands, if not in his words. A lesser actor would’ve been unable to make the audience forget the funny in what he was doing for most the play; Cruz was able to close this story with you tearing up like anything.

Credit for which must go to the leads of this play, particularly those kids, and especially Severino, who is kid through and through, but at the more crucial moments carries the emotional baggage of his character like an adult would. Believable anger is more difficult than tears for children in theater, and it is with the former that Severino actually seems older than he is, going at it for most of the narrative, and losing it altogether in the end. When he appears with Abuel in the final scene, it’s like a Cruz-Severino tag-team making sure you will cry.

Which brings us back to Lolo Pule and Abuel, one and the same, but different. There is something brilliant about age onstage, because it is not what we see on television, because it is without the trappings of wanting to look young(er) than we actually are. But more than that there is such power in Lolo Pule’s mere presence here, as a grandfather in the center of family and poverty, as the last vestige of folk healing, as the core of a grandson’s dreaming. There is wisdom here, the one that comes with age, but also more than that there is kindness, the kind that with Abuel’s portrayal seems to be part and parcel of having hands that heal. The kind that asks for little in return, the kind of healing that happens as a matter of belief.

Which is really what’s being said by “Totong Hilot” about hands that heal, as the same hands that bring family together, and ultimately reinvigorates the light that permeates not from happiness or wealth, but quietly and succinctly, from contentment. –KG, GMA News

"Totong Hilot" is written by Jose Dennis C. Teodosio and directed by Roobak Valle as part of Set D of Virgin Labfest 8, the one full-length play for this festival. "Totong Hilot" will be staged two more times, on July 4 at 8 p.m. and July 5 at 3 p.m., at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

More Videos

Most Popular