ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

My first flood

BY LAUREL FANTAUZZO

I knew something was up when the tricycle and jeepney drivers outside Saint Joseph’s all uniformly shook their heads at me in one massive, wet show of disapproval. “Savemore Sikatuna po?” I kept saying. They looked away, clicked their tongues, and said, “Baha.”

I knew what that word meant. It had been raining for days, but I had decided to venture out to a meeting in Ortigas from Quezon City anyway, tired of following the rain on Twitter and Facebook. I had watched Ondoy with terrible dread from the States in 2009, but I didn’t know, until now, how much of a flood was lived indoors and online for Manileños of means; how every smartphone, laptop, tablet, and cell phone was put to use for everyone to talk about the storm.

When I went online, I saw that there were suddenly no other subjects besides the rain. Here were tweets saying what streets were neck deep, knee deep, hip deep. Here were the maddening declarations that God had sent the storm to punish the Philippines for supporting birth control. Here was my friend Petra snapping back.

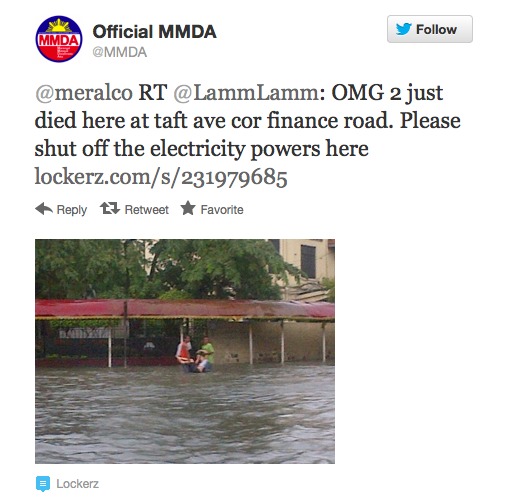

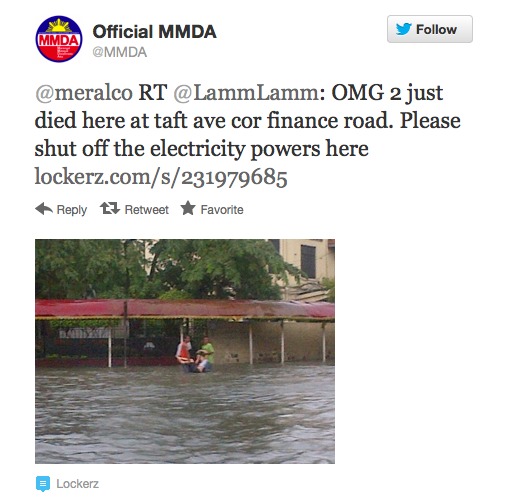

Here was a tweet that made me gasp and cover my mouth; the grainy cell phone photo of two drenched men bearing a dead drenched man, inert and helpless between them, electrocuted at the corner of Taft and Finance Road.

Here was Taft Avenue, turned again into River Taft. Here were my Philippine-born cousins warning me not to go outside. Here were the tweeted coordinates of residents stuck on the roofs of their submerged homes, awaiting rescue. Here were the worried status updates from my Fil-Am friends in the States, in Uzbekistan, Britain, Canada, posting photo galleries from the BBC and CNN, wondering how they could help.  Here was a knee-deep wedding.

Here was a knee-deep wedding.

Here was a knee-deep wedding.

Here was a knee-deep wedding. After hours of scrolling and scrolling at my laptop, I grew restless with the exhortations not to go outside. Twitter told me that the political organization Akbayan was collecting relief goods and summoning volunteers. That was within walking distance of my house. I walked in rubber shoes. I carried a backpack full of old clothes to donate. I helped pour rice into bags for flood victims in Marikina. I made sandwiches. I hopped newly hard-boiled eggs from hand to hand, putting them into crates.

At night I climbed into the back of an open-air cargo truck with other volunteers, on my way to Malanday Elementary School in Marikina. The drive, with traffic, took an hour or so. But now, few drivers were out in this. A dozen or so of us sat in the truck bed, a large rainbow umbrella and a rigged tarp as our shelter. We moved quietly through the strangely empty streets of Quezon City, the volunteers laughing every once in a while.

When we arrived at Malanday Elementary School, elderly men waited in wheelchairs far from the truck. Able-bodied evacuees of all ages pressed forward in a makeshift line, until Akbayan volunteers called for them to go back to the classrooms. The sandwiches and eggs would be delivered to them. The evacuees dispersed.

I stepped down from the truck. Small boys brushed against my pockets and looked up at me and my camera. I followed Akbayan workers as they handed out hard-boiled eggs and sandwiches filled with mayonnaise.

Families curled asleep inside classrooms, near blackboards and lesson plans. Or they sprawled in the corridors, along basketball courts, under aluminum overhangs. The school’s garden had flooded. Rain tore against every roof. Evacuees walked up and down the school stairs, holding huge black inner tubes still inflated.

“Ilan bata?” Akbayan workers asked, and placed hard-boiled eggs and plastic-wrapped sandwiches in the hands of mothers. Bicycles, metal tubs of taho, and small wagons rested on the outdoor balcony halls of the school—each a small symbol of a family’s whole fortune. Groups of teenaged boys lit cigarettes and called, “’Te. ’Te,” hoping for an extra sandwich. Evacuees caught sleep where they could; bent over a small desk, curled and pressed against a wall, on the floor with their arms flung over their eyes.

There was an air of routine in the school. These residents had done this before. It was an annual ritual. But what recourse did they have? Where else could they go? And so the rainy season exodus, and the eggs, and the sandwiches, and the eventual rebuilding of their tenuous shelters, after the deluge. No one will talk about them a week or so after this storm.

I didn’t like the sense of resignation. I didn’t like accepting this as true for huge swaths of the population; that I have the privilege of avoiding downed power lines and a swollen river and annual exile to the concrete floor or cement basketball court of an elementary school, while mothers my age reach for whatever eggs outsiders will bring them.

On our way back to Akbayan headquarters, the truck’s rainbow umbrella blew away suddenly, ripped up by a sudden blast of wet wind. We whooped and laughed, startled. I covered my camera with my jacket. From the open air bed, I could see the bloated river we were passing over. The gray slate water sloshed against the bottom of the bridge we were passing over. In a few hours the bridge would be submerged.

I went home and stayed home for a day after that, until the sun came out.

The sun. It was time for errands, and a meeting in Ortigas. I dropped off my laundry near Savemore Sikatuna. The MRT and LRT trains were still running, bless them, so I walked to Anonas and took one to Ortigas.

When I exited the Ortigas train station, the rain began again. I wore sneakers with socks and pants, which grew darkly drenched. My umbrella turned inside out. When my meeting was done, I forgot my other Ortigas errands and went back to the train.

Now, upon my return to Anonas, outside Saint Joseph’s church, the tricycle and jeepney drivers refused me to take me down the street I took every day. If I wanted to go home, I would have to walk. I wanted to go home. The storm was tiring. So I walked.

I wasn’t prepared for the vastness of the baha. I had never seen Anonas so uncrowded before. I had never realized how wide it was. The traffic, the vendors, the commuters, had been replaced by water, water, water. The water was gray. The water was like a gray field. Some children were playing in it, leaping in and out with the exuberance I’d seen at every summer community pool in the States. It doesn’t matter the conditions or their station in life, I thought. Children everywhere will always find a way to play in the street.

But this was baha, with all of its undercurrents, its stray lines, its opaque surface. Neck-deep, I noted, at Anonas and Tindalo, and yet a man still pushed his bicycle gamely forward in the flood. Waist-deep, I thought, as I pushed forward myself, wrecking my pants, trying not to think of power lines, thinking this was what I needed to do get home, so I would do it. The water was cool. Pre-teen girls in shorts and white T-shirts clutched their tsinelas around their wrists, laughed, and walked barefoot in the water around me.

I paused for a moment at the Anonas tailor’s shop. Inside it was quiet and normal, bolts of cloth leaning here and there in a mad rainbow, as always. I had noted the tall step before. The tailor had built the floor of his shop high enough beyond the floodwaters, used to it by now. He nodded, smiled at me, and kept sewing. “Baha, di ba?” he said. “Oo talaga,” I said.

It was a normal workday. A black cat slept nearby. I nodded. I felt wet and silly. I said goodbye, and went back out into the flood.

I sloshed toward Jollibee. My Laundromat was flooded, all of the clothes placed on high shelves, the owners used to this too.

I pushed toward the tricycle station near Savemore Sikatuna. I tipped my driver well. When I got home, I realized what I had done. I washed my legs thrice, with three different kinds of soap, thinking baha, baha, baha. Take doxycycline, my friends exhorted me. I had never seen that word before. I decided to stay home for a while.

In the morning the floodwaters would be gone from Anonas, strangely disappeared, as if they had never happened in the first place. Traffic would return. My laundry would get done. I will think of my friend Petra again, what she imagined as God’s only message to Filipino: “Clean your gutters.”

For now I logged back onto Twitter and Facebook. I scrolled down my feed. There were sketches by Paulo Alcazaren, explaining in a few moments why Manila floods so quickly now, and what could be done. There were tweets wondering what other countries the Philippines could use as a model for flood recovery. Indonesia? Malaysia?

I remembered that a few nights ago there was something about the force of the rain that penetrated my sleep. I’d fallen asleep easily at the start of the night, since the storm had no name; not Ondoy, not Pedring, not my name. If it was nameless, I assumed, it was likely harmless. Its effects would pass with no memory. Because what would people call it, anyway?

But the sound of the rain took up residence in my dreams. I heard it arriving and arriving, so relentless it replaced all other sounds, so relentless the water seemed to replace the air itself. When I woke, it roared.

I felt like the rain had been trying to tell me something all night. I thought I knew what it was now. I am a godlike storm.

I scrolled down now on my own Twitter feed. I found the quote I’d tweeted weeks before.

“There’s the storm, the Filipino’s god of all gods, which has somehow become the great paradoxical equalizer,” Lav Diaz said. The storm is the deity to which every Filipino must bow. Filipinos cannot deny the godlike storm. Wherever they are in the world. Whatever station in life they occupy.

I closed my laptop and looked out at the yard, all the plants bowed with rain. I thought about what I’d like to tell the storm. Give the country time. It’s trying.

I thought about what I’d seen over and over again on my Facebook and Twitter feeds, written by friends who loved the Philippines. In the motherland, and outside the motherland. If there was a collective people’s prayer to a storm, this was likely it. I repeated it now. Please. Be kind. –KG, GMA News

Tags: habagatflood2012, flood

More Videos

Most Popular