ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

The narratives beyond 'Ang Nawawala'

By Katrina Stuart Santiago

I took time to review any of the Cinemalaya 2012 movies for two reasons: (1) I thought that this year’s films, New Breed and Director’s Showcase, had many things going for them —including the fact of their diversity on the one hand, the noise that surrounded their screenings on the other— and (2) when monsoon rains can render 21 cities and provinces into states of calamity, then really, who even wants to write, much more read, movie reviews?

I also wanted to see the one that won for New Breed, just so I have a sense of where I stand, given a jury’s decision on these films. Today, I finally saw “Diablo” at the U.P. run of Cinemalaya. But that’s stuff for another review.

Right now it is reason number one that matters, because it is context for this review of “Ang Nawawala” by Marie Jamora. Truth told, I sat through this movie and thought: damn it, who are these people? What do they want from me? How can this be the movie that speaks to my generation? I sat through it and thought: good lord, why are they all speaking in English? Why are they all in vintage clothes? Why is that little girl called Promise? Why oh why was Marc Abaya in that wig?

One out of three

But I wanted to sit on “Ang Nawawala” as I did on all the Cinemalaya films I saw, because the days were long when I’d see three different films, and come home to tell my brother: one out of three was good. One out of three. That is no joke when you’re paying for P180-tickets, expensive mall parking, and/or gas to the Cultural Center of the Philippines in Manila. Then there’s the time wasted on films that are neither brilliant nor new.

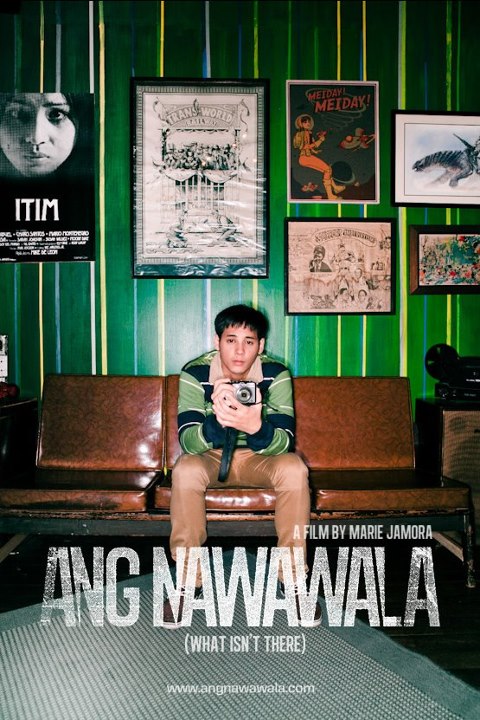

Poster from Ang Nawawala website

“Ang Nawawala” is not brilliant, but it certainly was new, and uncomfortably so. I needed distance from it, I needed the rest of the Cinemalaya films that I saw, to appreciate it for what it actually is: a film that got my exasperation, strapped as I was to my seat, because it was sold to speak of my generation (which is not its fault), and it dared to be unapologetic about this particular social class —which is all its fault, as it is its bravery.

Because when Philippine independent cinema has become a landscape of poverty and sex, danger and corruption, with a good dollop of religion, one does wonder from where the “new” will come. Here might be one answer: it is in stories like this one which we rarely see in the indie, but which remains new for local cinema in general because it is also a story that one wouldn’t see otherwise.This is no love story, no upper class bubble, that you would see in a commercial romantic-comedy after all, and therein lies our crisis with it as audience: if it will not survive commercial film making, why refuse “Ang Nawawala” the label of indie, why refuse it the fact of being so? Powerful conversations

Especially since it can only happen as an independent film, far more complex as it is than any rom-com you might see. For here is a boy in his early 20s, Gibson (Dominic Roco), who doesn’t speak because his twin died before his eyes at 10 years old. Here is a boy who falls in love with the first girl who doesn’t mind that he is voiceless. Here is a boy who renders a family quiet, highlighting the silences that do exist in long drawn bouts with grief. Here is a boy speaking to his twin, the residual guilt and self-pity transforming into conversations that are the most powerful ones in this movie, because they are the most real.

And yes, even that is a matter of insisting on conversations that are at the very least in Taglish, in both the imagined and real life of Gibson and his family. After all, even in upper class households, they would speak to their maids in Filipino, yes? After all, in real life, and in fact in the beginning of this film, Gibson’s mother (Dawn Zulueta) speaks to him in Filipino, but the film seems to forget that soon enough.

Because it is busy with other things, with accessorizing what is a familial crisis with layer upon layer of complexity: it is Christmas and New Year, it is a time of laughter and change, but the family has been like this for far too long, and they have aged in their grief, have stayed in that time when their little boy died. It is about the changed landscape of Manila, the cultural consumption that is also the creation of a particularly elite subjectivity that is being hipster, which remains undefined, even as it is all here: the interest in what’s vintage, the styling that seems out of place in Manila’s heat, i.e., wearing jackets while dancing and drinking to some rakenrol, the hand that always holds a camera. There is the requisite smoking of cigarettes and pot.

Complexity of silence This upper class landscape of course can only be made more complex by Gibson’s silence, and the character that arises despite, if not because of, it. He takes videos of people and places, instead of photos. He closes his eyes when he listens to music. He is shy about his work. He is your regular sensitive sad guy, whose crisis is this story’s unraveling. And you also understand how this social class, given this particular kind of youth it creates, particularly deals with this kind of emotional complexity. That is, it deals with them simply.

Closure happens through deletion. Change is borne of conversations with the self. This particular kind of youth is not so much superficial, as they are also in over their heads, dealing with the crisis of the present, with no worries about money, yes, but without much else. And so this movie does fall back on the clichés of love – romantic and familial and everything in between, and it falls back on an unraveling that is about a form of going home, literally and figuratively.

To some extent these resolutions ruined “Ang Nawawala” for me, failing as it did to see its own set-up complexities through to its logical lack of closure. In the movies and in real life, we would all know that closures aren’t all clean and shiny after all. For an indie film like “Ang Nawawala” the way for the crises to have been bigger and more believable as such would’ve been the refusal to even resolve it, to even tie things together. It might have succeeded had it settled for the silence of Gibson, as the world within the film had.

Real absence

And then there’s just the need for the film to have been more real. This coming home happens after three years of being away, yet Gibson is placed squarely and comfortably in the current terrain of popular culture, as if there was no time spent elsewhere. As if he was always here: his shelves had komiks published while he was away, his pot was ready to be rolled up and smoked the moment he entered his room. After three years? How?

Meanwhile, it is the world beyond the film and the discourse on local independent cinema that fascinates as well, given “Ang Nawawala.” I don’t know that we are still talking about it as a film, but what I do know is this: the appeal of this movie is precisely the fact that it is unlike the indie as we’ve come to know it in the past decade or so. Which is to say of course that this refusal to engage with the struggle of class altogether, just might be what it has going for it. We must trust that an audience will understand this as a limitation, even when it is enjoyable and familiar and fun, and everything in between.

Then too we must admit, that if we burst the bubble that is in “Ang Nawawala,” out will fall real people. How dare us say they are not worthy of starring in their own film. — TJD/KG, GMA News Katrina Stuart Santiago writes the essay in its various permutations, from pop culture criticism to art reviews, scholarly papers to creative non-fiction, all always and necessarily bound by Third World Philippines, its tragedies and successes, even more so its silences. She blogs at http://www.radikalchick.com. The views expressed in this article are solely her own.

More Videos

Most Popular