ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Art review: The daring of confessional art in 'Curved House'

Text and photos by KATRINA STUART SANTIAGO

The precariousness of confession is its promise: of a revelation, one that is grand because unexpected, one that will shock if not awe the listener, because what it can only be about is something we collectively silence. The admission as such banks on a truth that will be believable because possible, if not familiar. But what of the limits of confession, in as much as truth might only be revealed through words? What happens when it is art that functions as confessional, and art making becomes the confession?

This question informs the group exhibit of women artists entitled “Curved House,” which tasked itself with two intertwined difficult projects: to speak of the things we silence about the home on one hand, to pay tribute to Louise Bourgeois on the other. The former is a challenge more than anything else to render that which is not only personal but might also necessarily be painful or embarrassing or shameful through art making. The latter is about Bourgeois being the mother of confessional art, who did art as symbols by default of her real relationships.

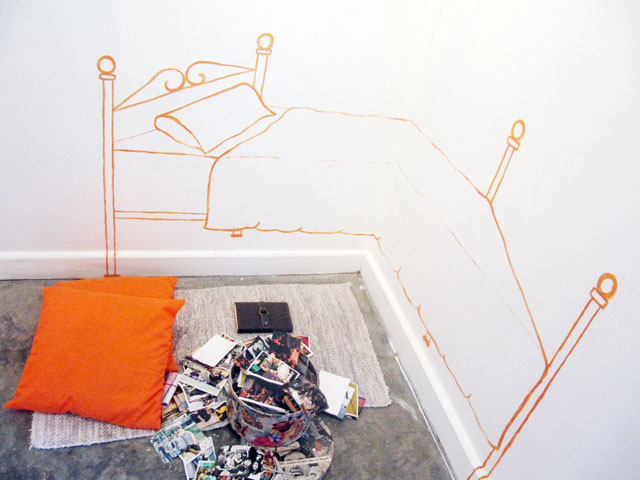

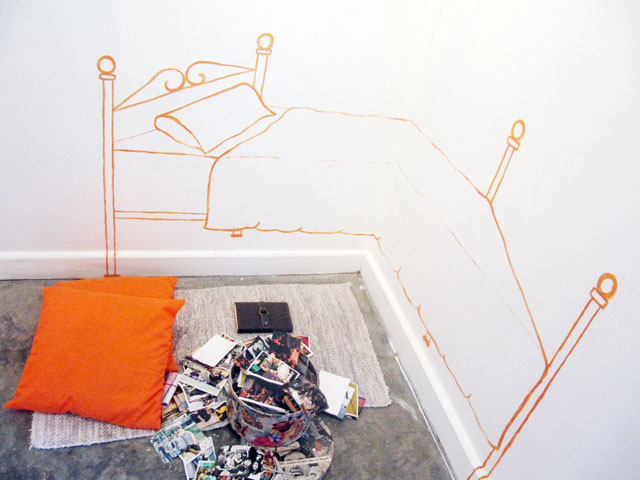

AJ Tolentino's "Ghost Looking In"

Uncomfortable with the question: what inspired you to make this piece of art? “Curved House” could only be a grand display of confessions about the home, the relationships within it, the crises contingent upon the woman’s roles in its making. In a nation where the creation of the home is a necessary engagement with the Pinoy Church and its rules, where marriages don’t end no matter how oppressive, where we are all expected to be obedient wives, and mothers who do not let our children go, therein lies confessions that might be personal, but can only speak to the collective. At least a collective of women that makes this the most uncanny of articulations: a collective confession? Maybe.

“Curved House” as such is that one space that is ours, the space created from the silences that abound in the homes women inhabit, the roles we fall into by default within the space. There is an almost grave silence in the many spaces of this gallery, within and beyond its walls, and you leave with a lump in your throat, one that’s more powerful than it seems.

The home's absence, instability

You are welcomed into the main gallery by AJ Tolentino’s “Ghost Looking In” with a flimsy drawing of a bed on the wall, (dis)connected from the carpet and pillows on the floor. Photos from a hatbox are scattered, like someone had just gone through memory and decidedly left them lying there for anyone to see. The absence here is eerie, the presence in photos makes it even more so. This play with absence and presence is also in Kiri Dalena’s “House,” a video loop of the façade of a shanty, the rest of its parts ravaged by the storm and flashfloods in Iligan. Here is what home becomes, in a time and space of loss, when the weight of one surviving wall is in the fact of its being but vestige, of people and family, the lone curtain that blows in the wind the most eerie reminder of movement and life.

Lia Torralba's "Trans-Plant"

Outside the main gallery, these silences and their weight, and the flimsiness of memory, are in three other works. Mimi Tecson’s “Rocking the Cradle” is a bright red structure atop one of cement post that frames a section of the garden. More like four different towers standing together, strings in red, yellow, green emerge are tied to it on one end, the gallery compound’s walls on the other. The effect is playful, with the strings hanging loose even as they attach to the house in a pattern, and it reminds of the instabilities that nurturing lives off, the kind of freedom we allow away from home, the ties that bind which are numerous and complex. Ling Quisumbing Ramilo and Tecson's "Once Upon a Time" is an installation on and against one of the garden’s larger trees, of what looks like a house made from found objects: long thin rods on which it stands, an old cabinet with frosted doors, a roof that looks like a house by itself. From within, a light shines brightly, and beneath the structure hangs what look like fruit made of colored jacks from the jackstones we used to play as children. On the other side of the tree, more jacks form the strangest of a vine-like growth on the tree, beneath which is nestled a tiny cabinet that holds an old key. The playfulness here is clear, the brightness a contrast to the bare minimum that the installation works with, all of it a statement on childhood memory under lock and key, of the brightness now held within structures we do not control, which stand on the most unstable of grounds.

Multiple women, memories

“Mana Mana” also by Quisumbing Ramilo meanwhile works precisely with the stability of generations, memories of women kept in chests filled with forgetting and remembering, one on top of another, from the biggest chest to the smallest one. A ladder stands to one side of it, speaking of the possibility of reaching for what’s on top of the pile, as it can only be about never knowing what it contains. Women, too, are in Kat Medina’s “Here Headless” within the gallery, a painting of three women’s bodies, backs turned, without faces, in spaces of home familiar—a wall here, a bed there. One head seems to be up in flames, another body is on a bed about to be attacked by a serpent, another is distant as if the one who walked away, if not the tiniest shadow of our ability at doing so.

Three faces meanwhile make up Eden Ocampo’s "Three Faces of Woman," white masks on what looks like a macramé installation hanging from the gallery’s ceiling. Sadly, from below, all you can really see is the haunting quiet of expressionless lips and empty eyes, and not much else. What successfully deals with the double-edged sword of stark whiteness though is Cathy Lasam’s “Buslo,” a woven piece that recreates the traditional crib for children, but which here is reconfigured with the sharpest of loose ends, dangerously jutting out from the structure itself. The dynamic between protecting the young, and the mother hurting herself, is what strikes you about this piece, as does its whiteness.

This double-edged sword in the roles that we play, these stories that women keep about themselves within the home, is also in Karen Flores’ “Impasse.” A white door that opens to a wooden wall filled with plastic insects and toys, the heart pillow on which a wedding ring might be carried, beneath which is the word “ran.” The power of this installation is in its seeming symmetry from afar, that false sense of order revealed only by coming up close. The dead end of false impressions, about marriage on the one hand, this particular confession on the other, is its power.

Ling Quisumbing Ramilo and Mimi Tecson's "Once Upon a Time"

Tribute to, conversations with, Bourgeois

Which is to say let’s have spiders and insects, some phalluses too, why the hell not. The larger works engage you in ways that are surprising if only because they depend on such intertextuality. Josephine Turalba's installation of "Need Crave and Obsession" is a spider creature that is both fearsome and decadent, bejeweled and in brass, its body in red, its head in intricate gold. The dynamic of attack and wealth is what’s in this installation, and the richness of it is palpable. As it is in Turalba’s two works on the wall, “Sacral Knot” and “Paraois Eternal,” both mixed media works that look like paeans to sameness and difference, as it is about being bound to certainty, being forced to go with the flow. The same might be said of her "Winds of Change" and "Lies and Lies" alongside Ari Turalba’s "Do-Minions," on the opposite wall of the same space, where flight is what resonates, and movement is default. All of Turalba’s work hanging on walls were this surprisingly brilliant and decadent-looking abstractions, that stood out against much of what was hanging on this room’s walls. This is especially true for Ambie Abano’s work, the largest installation of a drawing of a spider web against one wall, on either side of which are drawings of spiders that represent the artist and Bourgeois. But there was no way to read the string of words on which these spiders hung, and one is left with not much but a sad backdrop of a spider here.

On the contrary, Agnes Arellano’s 12 small sculptures were central to this room, as it was to this exhibit. Both a tribute and a conversation with Bourgeois, as it could only be Arellano’s own confession(s), “New Army for Fillette” takes from the former’s original work “Fillette,” a playful rendering of the penis, as un-scary and more importantly un-sacred, if not almost funny. Arellano outdoes herself in this army of sculptures that reveal the strangest of evolutionary processes from penis, to female or male, to birds. Yet the strangeness is outdone by the seeming logic in this process, the slowness with which it happens, from one to another, until it becomes person, until it is animal.

As tribute that works from what might be Bourgeois’ tradition, Arellano expectedly outdoes every other work in this curved house. As a conversation with Bourgeois, it is the fitting counterpoint to the air-conditioned hall to the left of the main gallery. Here, it is the quiet and the emptiness that strikes you, until you realize that it is here that the real and more dynamic conversations with Bourgeois are being had by the other women of this exhibit.

The hall that haunts

Bree Sim’s two installations, “It Is Understood I” and “It Is Understood II” play with the delicateness of living, and the concreteness of need and want. The first installation is half of quail egg shells, standing on very narrow legs on a bed of uncooked rice. At the center of each shell is the tiniest of pearls, evoking a sense of balance, but even more so a sense of precariousness. The second installation is a plate formed from cement, set against a pair of mismatched and tarnished utensils, heavy in their weight, yet the things they carry seem so much larger than that. Con Cabrera, Karen Flores and Rica Estrada's "Thus, Fixed" is also a motley collection of seemingly random old things: an antique watch, mismatched earrings, a glass votive candle holder, a necklace with the oldest of pendants. All easy to lose, all useless with age, all heavy with the weight of the memory it carries, the hands that held it.

At the end of the room is Rica Estrada, Lian Ladia, and Sidd Perez's "Runaway Girl," a zine on becoming artist on the one hand, conversations with Bourgeois on the other. It deserves a review all by itself, powerful and humorous as it is, very clearly placing the artist as it does in a space of smallness if not powerlessness. It is meanwhile Marika Constantino’s "the need for love and tenderness..." that might be the one work in all of this exhibit that dares take desire by the horns, and runs with it. A series of five abstract works in black and red, it is only distance that will allow you sense of what Constantino is doing here: where love is equated with two bodies intertwined, no beginning and no end, bound by one desire. The wonder in Constantino’s work is also its surprise: the space between spectator and work, the abstraction becoming concrete, the humor and strangeness that must be taken into consideration.

Dang Sering’s installation of chairs and paintings in “Conversations with a Crone” are as whimsical a tribute to Bourgeois, as light as a conversation with her, might be. Here, Sering’s ability at creating her smallness, her distance, works despite what seems like a premise of equality off-hand. Her slight of hand is in the details of tiny spiders crawling from the floor up to the paintings, pale blue insects crawling in random fashion, like conversations quiet and without direction. Against moss also randomly placed on the chair, on the wall, it is earth and sameness that resonates here.

And it is sameness, it is sisterhood, that one can only take from curved house. Where there is difference, yes, but there is no need for understanding or tolerance, because differences just are. These do not mean we are any less bound to each other by the spaces we inhabit, nor does it mean we must cancel each other out. It just means that in spaces turned confessionals, art that speaks of the personal made public, there is a version of us, a space for each one of us, there. Somewhere. –KG, GMA News

"Curved House" was curated by Con Cabrera and exhibited at the Blanc Compound in Mandaluyong in July 2012.

Katrina Stuart Santiago writes the essay in its various permutations, from pop culture criticism to art reviews, scholarly papers to creative non-fiction, all always and necessarily bound by Third World Philippines, its tragedies and successes, even more so its silences. She blogs at http://www.radikalchick.com. The views expressed in this article are solely her own.

More Videos

Most Popular