ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Caloocan public HS students challenged to read 20 books a year

By MEANN ORTIZ

Youth P.O.W.E.R. members participate in the end-of-season special activities. Photos by Debby Asuncion

Kalayaan National High School in Caloocan City has a population of almost 7,000 students. Located within the largest resettlement area in the country, the school has many students living below the poverty line.

It is a public school and could hardly turn any students away. As a result, each class could have as many as 75 students, each with varying abilities and skills. The conditions are barely conducive to compulsory studies, let alone an extra-curricular reading program.

Survey says…

The National Book Development Board’s 2012 Readership Survey shows some hopeful figures, like the increase in the number of Filipinos who start reading at a younger age, and that people are spending more time reading.

The survey also brings to light several factors that affect readership, most notably education, income, civil status, and the availability of reading materials. These factors are difficult to address comprehensively, so there is still a lot of work to be done if we are to raise a nation of readers.

Perhaps one of the most effective and yet difficult ways to try to overcome these readership obstacles is to establish a school reading program. It never hurts to start them young, right? It seems easy to implement on paper, but the reality is very different, especially if you’re working in a public school that has limited funding and very complex student demographics.

Readership is P.O.W.E.R.

For five years now, Kalayaan has been running a reading program called Youth P.O.W.E.R. (Promotes Opportunities for Worthwhile and Effective Reading), which encourages students to finish reading at least 20 books within a school year.

In 2007, reading program coordinator Debby Asuncion, along with her then first year high school students, helped to conceptualize and develop Youth P.O.W.E.R. as an enhancement program for independent readers and for those who finished remedial programs through the Department of Education’s Whole School Approach for Non-Readers and Struggling Readers. The program was also meant to develop English skills and to encourage students to “speak English without fear, without shame, and without guilt through storytelling.”

The program is supervised by the school’s English Department, but Asuncion says that they have made it a point to stress that the students own the program so that they will feel more invested in it. Members are in charge of registration, monitoring, and planning activities.

Participants gather for program orientation in a school hallway

Practical solutions

Asuncion admits that it’s been difficult to get people to join, let alone complete the program, so the school had to come up with various incentives for students.

Participants are issued a Youth P.O.W.E.R. membership card, which, Asuncion attests, also serves as a morale booster because possession of one indicates that you are part of a reading circle and have good reading ability. Certificates are also awarded to those who complete the Twenty Book Challenge (including teachers and family members who decide to participate), and medals are given to the top three students who have read the most books within the year. Program members can also earn extra class credits, as deemed appropriate by their respective teachers.

“The objectives and incentives are practical because it is what our school needs,” Asuncion says. “Students will not participate otherwise.”

Roadblocks and challenges

Aside from student participation, the program faces other challenges. The biggest hurdle is the lack of facilities to implement the program. This does not only pertain to physical facilities (reading circle meetings have been conducted along hallways or under the trees on campus), but also to the students’ tight class schedules, which do not allow for reading intervention activities. After-class activities are discouraged to prevent students from loitering without supervision, so participants have to find their own time to read.

There is also a lack of books available that students find interesting, or are appropriate for their reading skills. Asuncion notes that the school year when the program registered a record number of participants was also the year they received a big donation of new books that included many titles that the students actually liked. Let’s face it: reading a boring old book can only lessen the interest of an already struggling reader.

Library copies of popular books also tend to not stay long on the shelves, and most of the time when they are returned, they are no longer serviceable. And because the program relies mainly on donations and on a revolving fund from membership fees, Asuncion discloses that she has often had to use her own resources to buy used copies of popular new titles to keep the students interested.

“The books that I give the students are used,” she says. “I tell them that even if the books are dog-eared and torn, the text is still complete and the story is still the same.”

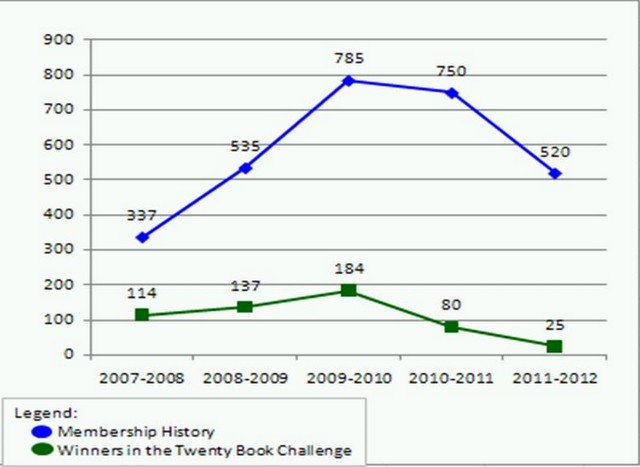

A chart shows membership and program completion statistics

Motivations and rewards

Even though implementing the program mostly seems like a huge struggle, Asuncion sees the value of continuing it whenever students succeed in completing the challenge, whenever she sees students reading books under the trees while waiting for their next activities, or hear stories from parents about their children saving up for books or checking out book stores when they go to the mall. She is also continuously motivated by the students who still cannot read or speak high school level English or even Filipino.

Asuncion hopes that school administrators and teachers can eventually find a way to make reading intervention activities and leisure reading programs mandatory. In the meantime, she is willing to work to make sure that her school’s program will continue with much-needed help from fellow reading advocates.

“I really want these students to be able to read books for fun, and I hope that will eventually lead into a habit,” she says. “I am distressed to see high school students with limited oral and reading skills, so I continue to motivate them to read and discuss the stories with them. The program works, and it will continue to work if people will support it.” –KG, GMA News

Youth P.O.W.E.R. is in need of more books to continue to support the reading program. Donations are welcome and may be sent through The Principal, Kalayaan National High School, Phase 10-B, Bagong Silang, Barangay 176, Caloocan City. Te. No.: (02) 962-8150

More Videos

Most Popular