Art review: Mooning | moaning over the Mona Lisa

There is no reason to be excited by “The Mona Lisa Project.” It is exactly what we expect.

That is, this is a tribute-by-default to the Da Vinci original, the one that has become iconic for many reasons including Dan Brown’s use of it as central image in his first bestseller off the Robert Langdon series. The exhibit note meanwhile attempts to talk about the larger critical history borne out of, if not against, the “Mona Lisa” as a way of contextualizing the exhibit.

I don’t know that reminding us of Marcel Du Champ’s “L.H.O.O.Q.” (1919), where he drew on a postcard of the “Mona Lisa,” is the right way to go. That project after all is far more complex than just a bunch of works, too many of which seemed too similar to each other. It also didn’t help that the CCP gallery was just too small for the number of works on display.

The vision isn’t any larger than this space; in fact, it is but a collection Soler Santos gifted to his wife Mona. And yet one would wish that there was more here than just the revelation that most of our artists might engage in a project such as this in exactly the same way.

Expected erasures, versions

It might be said that the easiest thing to do with being told to work from something, if not with it, is to erase the original. This is not problematic per se, but in an exhibit like this, it just seems to be a disservice to the individual works. That is, it all just seems too the same, given how they tightly fit in the space.

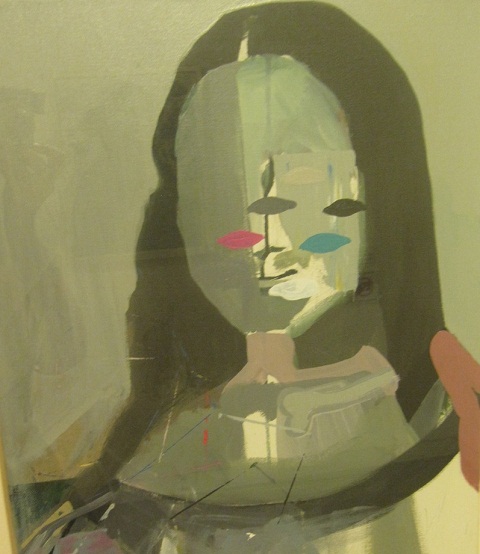

There is literal erasure of either the smile or the whole face, by shadows and drawings, few of them unexpected. These erasures as such were rendered by the exhibit the easiest thing to do, like telling a child to color over the page and not inside the lines. Worse, given the manner in which these works were placed beside each other, a whole section felt like a how-to-erase-the-Mona-Lisa lesson, not at all allowing each work to stand on its own, and not quite letting the whole set become something other than a collective erasure.

Here too, are countless reconfigurations, but sadly too many are no surprise. In these, the “Mona Lisa” is made into everything from monster to alien, one boob showing and hands cut off, fat and thin and everything in between. While many of these versions might be a surprise within a different set of works, say one that is not merely about the “Mona Lisa” but about a more complex project of tribute, in this particular context many of them disappear into the woodwork, and are nothing but the versions we expect.

The only thing worse was the lone work that drew the “Mona Lisa” in a different medium. But that was but one amidst all these works, and so it might have become the more distinct work, because unexpected.

The disappearing Mona

There were of course some successes, if one is to ignore the collective fail of too many in the exhibit, but too the conceptual vision that allowed for a real enjoyment, not of the “Mona Lisa” original, but of the work that was made from it.

MM Yu’s pile of pixelated photographs, in various colors, make for the imagination that it did come from a photo of an original Mona, magnified so many times, and cut up in pieces. It highlights both the fact of the original “Mona Lisa’s” integrity as image – it is said that what we see installed at the Louvre is not at all the original anymore; at the same time it highlights our belief in the reproduction, that is the captured image, and how true it is, despite the fact that technically and in reality it is but a bunch of pixels of a reproduction, far far from the original.

The two collages here also let go of the original Mona completely. And while Carina Santos’s work is done a disservice by its placement beyond eye level – particularly detailed as it seems – Sam Kiyoumarsi’s collage is in your face, and strangely enough, appealing. Kiyoumarsi’s puts together a woman from cut-outs, and fits this within the original frame of the “Mona Lisa.” This woman is Caucasian, with bright brown eyes, mouth taped and drawn with a red smile, and in a bikini, positioned awkwardly given the cutouts. Set against a lightbox, the backdrop looks like disconnected human ribs, if not flesh, creating a total picture that is eerily about a dismembering. Annie Cabigting meanwhile allows the original image to disappear by virtue of only recreating Mona’s hands. Put high up on a wall, it seems to look over the rest of the exhibit without eyes. Manok Ventura keeps those eyes, ones that don’t look over the exhibit, and instead are recreated within the frame of what looks like a map of landscapes. The less successful disappearances would be that one that just delivers an image of a flower, as it would be the digital work that merely put together images of an Indian sexy actress who uses the name Mona Lisa.

Annie Cabigting meanwhile allows the original image to disappear by virtue of only recreating Mona’s hands. Put high up on a wall, it seems to look over the rest of the exhibit without eyes. Manok Ventura keeps those eyes, ones that don’t look over the exhibit, and instead are recreated within the frame of what looks like a map of landscapes. The less successful disappearances would be that one that just delivers an image of a flower, as it would be the digital work that merely put together images of an Indian sexy actress who uses the name Mona Lisa.

The most successful disappearance of course would be the one work that takes it upon itself to literally reveal the act of losing the “Mona Lisa,” actually showing her erasure. Allan Balisi’s work is of a hand holding on to a drawing of the original Mona, with the other hand erasing the image within with cloth. In the end, Balisi’s work would be the most powerful statement against the erasures and disappearances of the “Mona Lisa” that are in much of these works. As such, it is also one of the more important works to see here.

Familiar hands, new Mona's here

And then there is a whole section here that you cannot but enjoy, if you are familiar with these artists’ works. Of course the latter is borne of how often they’ve exhibited, and the kind of place they’ve found within the landscape of contemporary artmaking; but also it is a tribute to their creativity that from afar you would know instantly: it is a Louie Cordero, a Zean Cabangis, a Dex Fernandez, a Romeo Lee, an Elaine Navas, a Dina Gadia.

Regardless of course of knowing to name these works from afar, is actually the fact that these are the works that will draw you in, if not call out to you. Lee’s Mona is the most anti-Mona of figures here, retaining as it does the general image, but working on it only with his own particular aesthetic of female figures: that is, literally larger than life. Navas’ impasto technique meanwhile creates an image of the “Mona Lisa” that looks sadder, yet in richer color and in seeming movement, her hands larger, and her face made more real.

Cordero brings his brand of grotesque pop art to his Mona, and the power is in the kind of control that disavows the original on the one hand, at the same time that it reminds us of it, even as there is barely the original here, save for the position the form takes. Cabangis reframes the Mona, cutting it at the hands, and placing it on top of the head; putting a frame askew over the face.

Fernandez’s skillful management of different media on that canvas is what works in the task of covering up not just the Mona but the rest of the canvas completely, and making her into the every woman, about to make spaghetti. Gadia’s mixed media work literally pokes a finger at her Mona’s eye, with the words “true confessions” across the image, reminding of how it is said that the mystery is in the original’s eyes, there is a glint it is said, as it does speak to you. And yet ultimately we know nothing about what it says.

And Chabet outdoes them all

Not surprisingly, the works that refuse to be bogged down by the “Mona Lisa” is what resonates here. There’s Don Dalmacio’s Mona, which keeps the original form of the head and few of the face’s features, as it reconfigures the whole picture via abstraction. It might be the latter that makes it unique compared to the rest of the works here, but also it is the light hand with which the abstraction is created, the choice of colors. In pastels and grays, with leaves and twigs, and the slight smile that remains, the effect is beautiful and fun, if not contemporary, without easily falling into the forms that are popular and digital.

There’s Don Dalmacio’s Mona, which keeps the original form of the head and few of the face’s features, as it reconfigures the whole picture via abstraction. It might be the latter that makes it unique compared to the rest of the works here, but also it is the light hand with which the abstraction is created, the choice of colors. In pastels and grays, with leaves and twigs, and the slight smile that remains, the effect is beautiful and fun, if not contemporary, without easily falling into the forms that are popular and digital.

Ryan Villamael’s reconfiguration also effectively makes the “Mona Lisa” more beautiful and contemporary, by virtue of a papercut that’s put over the original image, one that is both whimsical and flimsy, covering the image just enough to change her, and remind us of what we know the Mona Lisa to be: delicate and mysterious.

Yasmin Sison’s painting was also unique among these works, as it is the only one that effectively displaces the “Mona Lisa,” making it but part of the picture and not all of it. That is, this is an image of an unkempt room, with a bed and a dog, gray walls on which hang one “Mona Lisa” painting. Here the original work is nothing but secondary to the scene, and the scene is also far from being extraordinary.

Which is what Roberto Chabet’s contribution here ultimately works from: the refusal to engage with the “Mona Lisa” as extraordinary, and by virtue of that reconfiguring it as the commercial how-to product that teaches anyone how to paint. With the diptych of one white and one black outline of the original Mona, Chabet points to the fact of the Mona’s commercialization and the image’s contingent normalization as something that anyone can paint. At the same time, it speaks of how overrated an image such as this might be.

And in an exhibit that by default highlights the “Mona Lisa” as extraordinary – erasure, defacement, and all – Chabet’s can only be the most powerful work here. Also the most critical.

Which brings me back to this: in 21st century Manila, one wonders what is the point of such a large group exhibit such as this – large owing to the number of participating artists, of course. Because the “Mona Lisa” might be iconic and all, but it would seem that we might set our sights on something else, a different image to play with, and critique through our artmaking, particularly one that is grounded here?

Recently, Geraldine Javier’s “Curiosities” put up Fernando Amorsolo’s “A Filipina-Hindu Mestiza” (1947) and Jose Pereira’s “La Morena” (1946) at Vargas Museum. Would those two images make for an astounding tribute? Wouldn’t that kind of project be more relevant, more exciting to do for these times when we cannot even begin to talk about being woman in this country? Art then would be about engaging an audience in a discussion about art and creativity, and the kind of imagination it has about our own women.

Now that would be an exhibit that matters. -- YA, GMA News

“The Mona Lisa Project” runs until June16, 2013 at the Bulwagang Fernando Amorsolo (Small Gallery) of the Cultural Center of the Philippines Main Buildling, Roxas Boulevard, Pasay City.