Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

'I would rather die on my feet with honor': A Ninoy Aquino timeline, 1968-1983

Thirty years ago, Senator Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino Jr. stepped off a plane and into the firing line of an assassin. It was the end of a life lived in courage, and the beginning of the end for a powerful dictatorship.

Below, a timeline of the events from Ninoy's days as a young senator—and already a thorn in Marcos's side—until his death.

1968

Some say that Ferdinand Marcos made up his mind to impose martial law in 1968 when Ninoy, rich landowner, former mayor of Concepcion, former governor of Tarlac, and newly-elected senator (despite attempts by Marcos to have him disqualified for not meeting the age requirement and alleged communist-coddling)—proved a threat to his leadership.

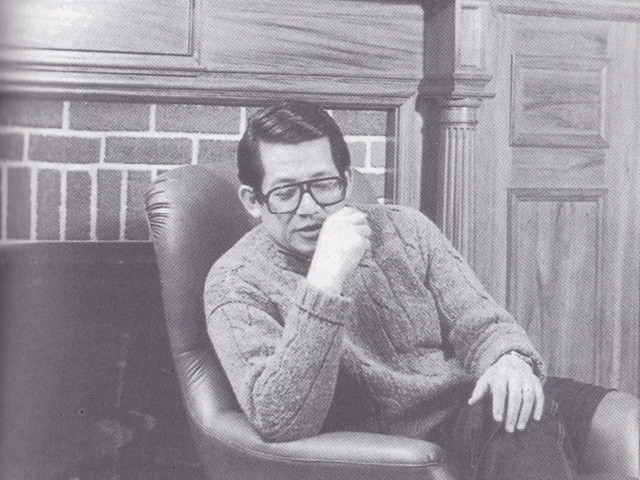

The young Senator Aquino in 1967.

In Ninoy’s maiden speech on the Senate floor, he mounted a political assault on Marcos, charging that the President plotted to make a “garrison state” of the Philippines.

Marcos, sensing the senator’s eye on Malacañang, resolved then, it is said, to frustrate the immensely popular Ninoy and punish his old-rich, high-society feudal-lord backers (who persisted in snubbing Marcos’s wife Imelda, a poor Romualdez) by perpetuating himself, the leading new rich, in power.

1969

Others say that Marcos made up his mind about Martial Law in 1969. While he had just won a second presidential term amidst allegations of vote-buying, military terrorism, graft and corruption, he was faced with armed insurgents on two fronts—in Mindanao, Nur Misuari’s Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) sought to free Muslim Mindanao from Christian domination; in Luzon, Jose Ma. Sison’s Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) sought to free the country from the evils of colonialism, feudalism, and capitalism.

The CPP’s military arm, the New People’s Army (NPA), was led by former Huk Bernabe Buscayno, a.k.a. Ka Dante, known to be a friend of Ninoy’s. Rumor, subsequently confirmed, had it that the senator was instrumental in bringing Sison and Ka Dante together.

January 30, 1970

Still others say that it was with the outbreak of the First Quarter Storm in the first month of Marcos’ second term, when military troopers daily and violently dispersed student demonstrations, and Marcos let float the scheme to change the Constitution and shift from a presidential to parliamentary system to keep himself in power, that set him on the inexorable path to military rule.

1971

Events began to accelerate to anarchic proportions with bombings left and right, the largest of which was the Plaza Miranda bombing in 1971 that maimed several opposition stalwarts. The handiwork of Marcos, charged the Liberals; the handiwork of the communists and Ninoy, charged Marcos. He suspended the writ of habeas corpus and swamped the nation with disinformation that exaggerated the communist threat upon which he built his case for martial rule.

Whatever the true story, it is clear that the imposition of martial law was premeditated. Marcos anticipated and prepared for all contingencies, including the drafting of a new constitution in 1971 that would allow him to run for a third term and possibly rule for life.

September 13, 1972

A little more than a year after the Plaza Miranda bombing, Ninoy in a privilege speech exposed and denounced “Oplan Sagittarius,” allegedly the president’s game plan to place the national capital region under military control. On September 16, Marcos accused Ninoy of meeting with Communist Party leader Sison and plotting to overthrow the government.

Sept. 21, 1972: Marcos proclaims martial law.

Marcos signed Proclamation 1081, declaring a state of emergency and proclaiming martial rule, allegedly to prevent the communists from taking over the nation.

The proclamation was to be implemented only upon his clearance, and that clearance was given the next evening soon after the car of his Defense Minister, Juan Ponce Enrile—known as the architect and chief implementor of martial law—was reportedly ambushed and riddled with bullets.

No one was harmed, but it was enough to create an illusion of disorder and danger to the Republic.

The moment that the news was out via government TV Channel 4, Enrile received Marcos’s go-signal and the military swept into action, closing all privately owned newspapers and radio and television stations, and arresting the more virulent of Marcos critics in politics and media. Number one on the list was Ninoy.

September 21, 1972

Ninoy was at the Manila Hilton the night Martial Law was declared, attending a legislative committee meeting. The phone kept ringing—mostly friends in and out of the Marcos camp calling, urging him to run. But he stayed, and went quietly when the military came to pick him up past midnight. He was brought to Camp Crame, headquarters of the Philippine Constabulary, and presented to the chief, General Fidel Ramos, who was personally in charge of rounding up the initial high-visibility list of 400 alleged “subversives.”

Ninoy thought the people would rise up in anger and resist censorship, curfew, and the closing of Congress. He thought they would take to the streets in protest and demand the return of democracy and the freedom of all political detainees. But most of the brave ones of the protest movement were, like him, in jail. The few who managed to escape the military dragnet had either gone underground with the communists or escaped to America. Many more who stayed behind retreated into shells of silence, not just from fear of the dictator and his abusive military, but also thanks to clever propaganda that had the masses believing in the promise of a New Society, particularly the promise of land reform.

January 1973

KBL-organized “citizens assemblies” ratified the Marcos Constitution with a show of hands. A few months later, anti-Marcos groups, moderate and radical, quietly gathered under the umbrella of the communist National Democratic Front.

Ninoy and Senator Jose “Ka Pepe” Diokno, considered Marcos’s strongest opponents, suddenly disappeared from their prison cells in Fort Bonifacio; their wives had no idea where they were and whether they were still alive.

The foreign press picked up the story and focused anew on the Marcos regime’s continued violation of political detainees’ human rights. Not long after, Ninoy and Ka Pepe were returned to Fort Bonifacio, direct from Fort Magsaysay in Laur, Nueva Ecija where they had been stripped of clothes and personal effects and put in solitary confinement in small, poorly ventilated cells that were lit day and night.

August 1973

A military tribunal charged Ninoy with subversion, collusion with communist Ka Dante Buscayno in a 1957 murder, and illegal possession of firearms. Ninoy refused to participate in the trial which he denounced as an “unconscionable mockery of justice”: no military court would dare find him innocent. To defend himself would mean to recognize the authority of the court and, in effect, of the dictator.

“I would rather die on my feet with honor,” he said to the tribunal, “than live on bended knees in shame.” Witnesses burst into applause.

The trial was suspended for a year and a half.

1973-1975

Ninoy's detention cell. Gov.ph

They found out later that visits were tape-recorded, which reportedly is how his jailers found out that Ninoy had an intelligence network in the military that continued to report to him while in jail.

Ninoy was up to date on recent developments; he knew that Enrile kept dossiers on Imelda and her brothers, that Fabian Ver and Imelda were spying on Enrile, and that arms shipments were being received by Muslim guerrillas from sympathetic Arab countries.

March 31, 1975

The trial resumed. Ninoy went on a hunger strike in protest, to no avail. The trial proceeded even though it meant forcibly taking Ninoy to court. After a month, having lost 40 pounds, Ninoy was rushed to the Veterans Memorial Hospital. He seemed resigned to die, or waste away. But his wife, his mother, and his father confessor pleaded so hard, he made a deal with his Creator—if he survived 40 days of fasting, it would be a sign that he was meant to live, that he had unfinished business to take care of.

November 1976

Jimmy Carter was elected President of the United States. For the first time, the White House requested Malacañang Palace to release Ninoy and allow him to retire in America. Afraid that Carter would make a hero of Ninoy, Marcos and Imelda ignored the request. Carter did not press the issue; he was negotiating rent for Clark Air Base and Subic Naval Base way below the $1 billion that the previous administration had offered.

June 1977

The military proceeded with Ninoy’s trial even if the Supreme Court still had to decide on Ninoy’s petition that he be tried by a civilian court. On June 21, in response to his request, Ninoy was fetched from jail and brought to the Palace. According to witnesses, the Upsilon Sigma Phi brods chatted like old friends. Again, Ninoy pleaded that he be tried in a civilian court. If convicted, asked Marcos, would he ask for forgiveness? No, said Ninoy, I have done no wrong.

The trial continued.

November 25, 1977

Ninoy and Ka Dante were sentenced to die by firing squad for rebellion, murder, and illegal possession of firearms. The world howled in outrage. Marcos backed down and allowed Ninoy to elevate his case to the Supreme Court.

April 1978

Under pressure from the US government, Marcos had allowed Ninoy to head a new party, Lakas ng Bayan (LABAN) and from his prison cell to run for a seat in opposition to KBL’s frontrunner Imelda. A month before elections, Enrile went on TV and charged Ninoy of being both a communist and a CIA agent.

Ninoy demanded equal TV time and got it. It was his first appearance on public television in almost six years, and the nation was enthralled and shocked at how much weight the once chubby senator had lost. For people who voted him into the Senate in ’71 there was a poignant sense, long overdue, of how terribly he must have suffered, and continued to suffer, under Marcos rule. And yet the man had lost neither his ardor nor his bite and the people took little convincing that Enrile lied: Ninoy was neither a communist nor a CIA agent.

Except for that one TV appearance, Ninoy’s campaign was left to his wife Cory and seven-year-old Kris, whose rallying cry was, “Help my Daddy come home!”

April 6, 1978

On the eve of elections, Ninoy’s secret admirers responded under cover of darkness with the historic noise barrage. At 7 p.m. on the dot, they took to Manila’s streets yelling, “Laban!” and making the L sign, accompanied by car horns shrieking, pots and pans banging, whistles blowing, sirens wailing, church bells pealing, and alarm bells ringing, never mind if the dreaded military picked them all up.

This was the first time, five years into martial rule, that the people made their presence known, loud and clear.

The noise barrage did not win Ninoy the election that was marked by massive cheating, but it told him in no uncertain terms that there were Filipinos out there like him, anonymous but increasing in number, who were yearning for freedom. These people were not to surface for another five years.

January 1980

The first polls for mayors and governors were held; certain that the KBL would cheat, the Liberal Party, Ninoy’s LABAN, and the Left boycotted the elections.

March 1980

Ninoy suffered a heart attack due to blocked arteries.

May 8, 1980

Ninoy was allowed to fly to America for surgery. It was a dark time for many people, who felt abandoned, even betrayed. Until news from abroad, smuggled in and xeroxed for distribution, revived their spirits. All was not lost.

Ninoy in exile. Benigno S. Aquino Jr. Foundation

Three months into exile, Ninoy was back on track, making speeches, denouncing Marcos, Imelda, and Ver, and, against everyone’s advice, talking of going home.

Addressing the Asia Society in New York, he warned that if Marcos did not lift Martial Law, the situation in the Philippines would deteriorate, marked by “an escalation of rural insurgency” and “massive urban guerrilla warfare” that he intended to join.

In the same speech, Ninoy avowed that “the Filipino is worth dying for.”

August-October 1980

Within three weeks of Ninoy’s warning, the April 6th Liberation Movement set off its first bombs in Manila, followed by two more waves of explosions in mid-September and early October, topped on October 30 by the bombing of the convention of the American Society of Travel Agents just after Marcos delivered a speech assuring delegates of peace and order. Greatly embarrassed, Marcos sent Imelda to New York for talks with the opposition; Ninoy demanded the lifting of Martial Law and the holding of fair presidential elections.

1982

Marcos planned for his family to reign supreme and kept his illness a secret. The plan was for Imelda to take over, and then Ferdinand Jr.—with Ver’s support. Indeed, it was a matter of great concern for both Enrile and Ninoy. Enrile didn’t put it past Ver to preempt Imelda at the first opportunity, while Ninoy didn’t put it past the communists to preempt the legitimate opposition.

Against all advice Ninoy made plans to come home. The Marcoses reportedly freaked out; they had more than enough problems to deal with—they were running out of cash, opposition to the regime was mounting, media was finding its voice, even the presidential kidney was asking for a change. Ninoy they could do without.

Early 1983

The Defense Ministry admitted it was holding more than 500 “public order violators,” which included those imprisoned for national security crimes, such as subversion, insurrection, rebellion, and illegal possession of subversive documents or firearms; the Manila-based Task Force Detainees’ estimate, as of 1983, was 963.

May 1983

Imelda met with Ninoy in New York. Reporting a threat on his life, she advised that he put off his homecoming. But Ninoy sensed that Marcos was seriously ill, and in any case wanted to be home early enough to prepare for the 1984 Batasang Pambansa elections.

His mind was made up and his life was in God’s hands. If spared, he swore that he would, like Gandhi, continue the struggle to liberate the country through non-violent civil disobedience.

June 1983

Ninoy bid the US Congress goodbye.

Early August 1983

Ninoy was scheduled to come home on the 7th of August but a few days before, he received a telegram from Enrile that confirmed the threat on his life and advised him to put off his travel plans even just for a month.

August 1983

Before leaving Boston, Ninoy prepared a speech he meant to give upon arrival at the Manila International Airport (MIA). “According to Gandhi,” it said in part, “of all the responses of God and man to oppression, nothing is more effective than the sacrifice of the innocent.”

August 21, 1983

It had been three years since Ninoy first declared that the Filipino is worth dying for, and he proved it on the 21st of August 1983 when he came home, was escorted off the plane by Marcos’s military, and assassinated in broad daylight, allegedly by an ex-convict.

Ninoy never saw the yellow ribbons adorning trees and street posts; he didn’t hear the people, silent no longer, sing “Tie a Yellow Ribbon” in welcome. Yellow was the color of the movement and Radio Veritas the voice of the opposition. Veritas, owned and operated by the Catholic Church, was the only station that dared broadcast the assassination and relay the nation’s shock and dismay. No one doubted that Marcos was to blame, never mind who pulled the trigger. Even the elite minority was offended—if he could do it to Ninoy he could do it to them.

Relatives and friends release doves to mark Ninoy's 24th death anniversary in 2007.

They came in droves to the Aquino home on Times Street, Quezon City and quietly, bravely, lined up for a glimpse of his bloody remains and to bid their fallen hero goodbye.

On the day of the funeral, millions left their homes and workplaces to march and line the streets where Ninoy’s casket would pass, and they raised their fists, sang “Bayan Ko,” cried “Ninoy, hindi ka nag-iisa!” — BM, GMA News

This timeline was culled, lightly edited, and restructured by Katrina Stuart Santiago from the chapter “Roots of EDSA, Marcos Times” in the forthcoming book “EDSA Uno, A Narrative and Analysis with Notes on Dos and Tres” by Angela Stuart-Santiago.

More Videos

Most Popular