ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Leloy Claudio talks narratives and nationhood at the launch of his first book

By REN AGUILA

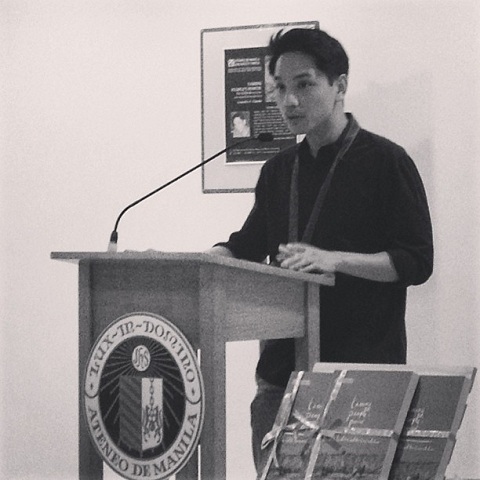

Ateneo professor Leloy Claudio speaks at the launch of his first book. Photo courtesy of Shinji Manlangit

“Around 2009, I was thinking about what to write, and initially, I wanted to write about the Seventies,” Claudio told GMA News Online, “just because the Seventies was an interesting period in Philippine history.” Part of him also wanted to revisit the story of his parents, who were activists fighting the Marcos dictatorship at that time, and the story of the Left, especially of the Communist Party.

But Corazon Aquino’s death prompted a re-thinking. “The way to really write about the Marcos era for me,” he said, “is to refract it through the lens of People Power, because [it] is such a strong mythology.” He added that Cory’s death for him marked a strong “tectonic shift” in Philippine politics because of “how we think about those symbols, and how people respond to it.”

The power of People Power

Claudio’s book explores how the narrative of People Power was shaped and how it influences contemporary politics. He also had in mind the story of Hacienda Luisita, a major area of concern that still generates tension even between Aquino and his social democratic allies. “It’s a historical book,” Claudio says, “but I hope its relevance is contemporary.”

He is critical of the way that the narrative of People Power has been used to justify elite dominance. “It has often been used to justify replacing corrupt leaders with leaders who are sometimes better but ultimately belong to the same political class,” he said, arguing that while it was good that Marcos was overthrown, the eventual replacement was someone from the landed elite. He notes that Hacienda Luisita, which a good part of his book deals with, is a symbol of that tension in the narrative.

In a sense, he argues that the contemporary anger over the pork barrel scam is part of the rejection of both this narrative and the competing narrative of the national-democratic Left. Neither are viable because, in many ways, they both represent homogenizing and (in the case of the latter) even totalitarian thinking. “A lot of [the anger surrounding the pork barrel scam] is because people are not happy with the existing alternatives,” he says, “[and] if you look at the people who went to the [August 26] rally, a lot of them were not just critical of the system…they were also critical of the people massing outside, the front organizations of the CPP who were putting up signs like ‘Oust Noynoy,’ etc., and nobody was paying attention to them!”

Claudio’s answer to the political crisis would surprise many who are aware of his left-wing politics: “What we need is a democracy that is responsive to present circumstances.” He believes the way forward is to strengthen liberal democracy, and not to rebuild society, as he puts it, either through a one-party Communist state or a restoration of the New Society Marcos promoted. This is a view, he admits, that many of his colleagues in the Left are angry with him for espousing. He adds that reforms to the electoral and political system which reduce the role of money in the electoral process, for instance—including removing “pork barrel”—would enable better leaders to be chosen. It also involves strengthening things like education, he believes.

No to homogeneity

At his book launch, the band known as the Strangeness played for the first time at the Ateneo de Manila. The Strangeness are notable for what Claudio calls “tito rock,” evoking the era which, as was said, fascinates him. “My interest in the Seventies is not just anchored in the activism,” he says, “but in a broader interest in the counter-culture that was vibrant then.” For him, few bands, including this one (who are his friends) capture that spirit well.

Claudio’s rejection of totalizing narratives—a postmodern view if ever there was one—extends to his own views on the Philippine musical culture of today. He finds music here exciting precisely in its diversity. “It’s not for me about the rise of a homogenous ‘OPM’ united under one nationalist banner,” he said, “because music was never like that; music was ‘letting a hundred flowers bloom.’” An ironic image for this avowed anti-Maoist, he admitted, but he added, “A hundred flowers are blooming, so if you find a particular flower that you like, appreciate it.”

In both culture and politics, Leloy Claudio aims to challenge totalizing narratives. It is this work that has won him both admiration and criticism, and at the same time a good deal of respect. But it is vital work for a society that is experiencing the bracing winds of change. — BM, GMA News

Leloy Claudio’s new book "Taming People’s Power: The EDSA Revolutions and their Contradictions" is now available at the Ateneo de Manila University Press and in bookstores.

More Videos

Most Popular