ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

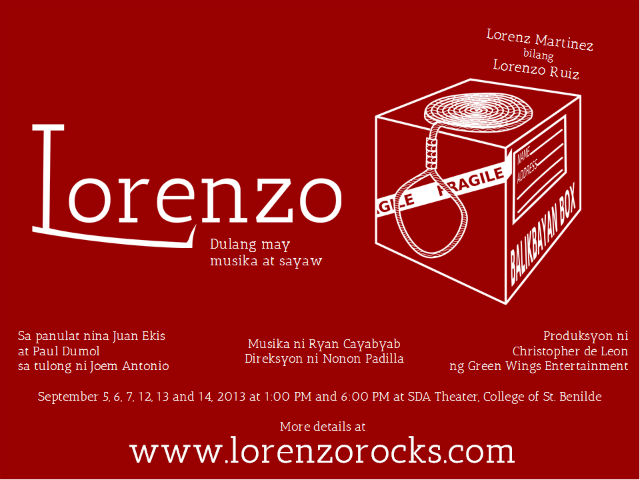

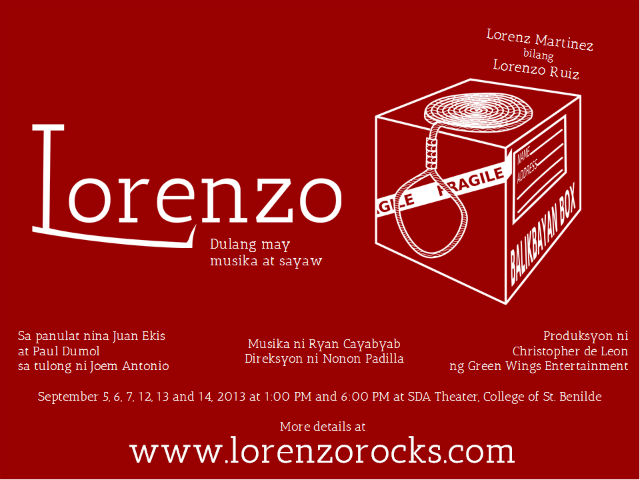

Theater review: When a play preaches: A look at 'Lorenzo'

By KATRINA STUART SANTIAGO

It’s not necessarily a bad thing. And certainly we might argue that all plays, if not all cultural texts, preach something, have as goal some lesson or other.

But there is much to be said about a play like “Lorenzo” which is already imbued with the lessons that are in the life of one Saint Lorenzo Ruiz.

The real story of St. Lorenzo Ruiz, the first Filipino saint beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1981, later elevated to sainthood in 1987, is sparse. All we know is that he was a layman, who had to leave a family in Manila when he was sent to Japan by the Dominican Order, for which he had been working as a scribe. Lorenzo left Manila in 1639; it is believed that he was sent away because he had committed a crime against the Spaniards.

The little of Lorenzo’s story that we know is the space that the musical “Lorenzo” navigates, toward teaching us all the lessons we must learn from his life, of sin and sacrifice, and conversion.

What this play believes

Or who. Which is obviously God and his grace, and that’s all well and good. At the same time there was a failure here to go beyond the white and black of good and evil, and as such the preaching trumped the play.

Which is to say that it certainly belabored the points it wanted to make. This is a three-act play about the martyrdom of Lorenzo Ruiz. That’s three acts about a man who we have very little information on, and whose crises this play really only reimagines.

“Paglalakbay sa Kamatayan” seemed like the perfect Act One, which revealed how Lorenzo left Manila, arrived in Japan, and was an outsider even to the Christian missionaries who were in hiding there. But “Ang Krimen Ni Lorenzo Ruiz” and “Ang Pasyon ni Lorenzo Ruiz,” Acts Two and Three respectively, could’ve been edited down to one final act. It could’ve taken us to the climax that is Lorenzo’s suffering and his death, without forcing us into every psychological crisis there is, not just in Lorenzo, but in the four other priests and missionaries who were in jail with him.

And let’s not forget Laurence (OJ Mariano) and his crises. An overseas Filipino worker in jail for killing his employer, Laurence is in fact the one in charge of the narrative about Lorenzo that unfolds on stage. Because he is the writer of the play within the play, that is, Laurence is watching the play he has written unfold in front of his eyes, at the same time that we are watching it.

Obviously the point was to show the parallelisms between Laurence’s and Lorenzo’s stories. Because Laurence is an OFW, away from nation as a matter of need, and all the way in the Middle East is convicted for killing his employer—a man who raped him. He is angry with God. What we know of Lorenzo’s story meanwhile, is flimsy at best, and we have no sense at all of what it was that he had done in Manila to warrant being sent away to Japan. It is not clear in any of the stories about Lorenzo that he ever got angry with God, or that he doubted it for one minute.

In this play Lorenzo’s silence is reason for a long-drawn discussion about what he had done. In Act Two the priests play a guessing game about it, and the conclusion was that he had killed a Spaniard because the latter had raped Lorenzo’s daughter. Or no, his son. Because according to this play that would be “Mas karimarimarim.”

I cringe.

What this play ends up doing

Is to portray Lorenzo Ruiz against the life of a convicted OFW Laurence, whose sins and story are clear. It is obvious here that the parallelism doesn’t hold, and yet “Lorenzo” will take you for a ride through its justification, and how.

By thinking it is already more complex that there is a writer of the musicale within the musicale. And yet it isn’t careful about making sure the interventions of Laurence on the unfolding story of Lorenzo are consistent, or rational. In fact, Laurence’s conversation with the Filipina reporter at the beginning of each act messes with the unfolding of Lorenzo’s story, what with Laurence already explaining what it is he sought to do in each part of the play.

That is, he says: In this act, I am Lorenzo; in this one, I am Lazaro. That is, Laurence explains why he has written about Lorenzo in this way, and at some point it seemed like the voice of the creators of this play themselves, making sure that it all makes sense to the audience what it is they are trying to do.

Except that what they were trying to do isn’t exactly what happens here. Because too, there was the use of Japanese pop culture references as intertext that seemed like half-hearted and thoughtless efforts at getting a young audience interested. Worse, I cringed at the seeming political incorrectness, the lack of a historical backbone for these portrayals, if not the grace to portray the contrabida beyond archetypes and stereotypes.

Granted that good and evil, Lorenzo and the Christian missionaries versus the Japanese authorities, could be black and white. But there can only be a need to contextualize whatever it is we deem as evil in the kind of time period in which it existed. The Edo Period was when Lorenzo was in Japan, and certainly there is enough information available about the complexity of that time in terms of Japanese politics and culture.

Certainly there was a need to be careful in portraying this time to have been about nothing but the suppression of Christianity and prosecution of Christians, because of course the other side of that coin was Confucianism that was at the heart of the Edo Period’s social structure, and which was a crucial part of its ideological backbone.

To have portrayed the Japanese as mere archetypes of evil was not only simplistic, it was also unjust. It also seemed like a cop out for a story that wanted to talk about the value of the life of Lorenzo, to have refused the more difficult conversation of two beliefs going up against each other.

What this play has

Is a lack of control.

That is, the Japanese references are too much and don’t really work, including the sudden appearance of a screen that projects comics illustrations of the possible crimes that Lorenzo committed in Manila – an effort at going all “Rashomon” on us. To say that it was an epic fail is an understatement.

Though maybe the biggest pop culture reference fail is that of the Voltes V that appears out of nowhere for reasons that are beyond one’s comprehension. And have I told you about how the rock ‘n’ roll would turn heavy metal, if not punk rock, the moment it was the Japanese singing and criticizing Christianity? How’s that for subliminal messages?

But maybe the only things worse than the portrayal of the Japanese here, as well as the thoughtless intertextuality, is the way in which we are made to imagine crisis and undoing, and the final conversion, to happen.

We are not allowed to imagine it. Because when they have Lorenzo struggling with his burden, they actually give him a burden. That is, they make him wear a bright orange human-shaped stuffed doll on his back, which the poor actor had to dance with, while he also danced with a human version of that doll, wearing the same orange outfit.

Because every moment that speaks of Lorenzo’s or Laurence’s conscience or innermost struggles came with a dance number. That is, dancers would walk in and dance to explain to us all what the characters are thinking. That the choreography had no rhyme or reason just made the presence of these dancers even more irrelevant; interpretative dance is just too … “That’s Entertainment” for comfort here.

All these made for a production that might have had as goal to teach a lesson or two, but really quite ended up with a long-drawn discussion about that lesson or two. It obviously does not make for good theater, and yet these two are not mutually exclusive.

There is a way to make theater work for the task of teaching a lesson or other, if not the lessons that are in the life of a religious icon, or which is in Catholicism and Christianity. Trumpets has proven it can be done. Without a doubt, this play had everything going for it: Ryan Cayabyab as composer and overall musical director, music and singing that was by most counts interesting enough, Mariano and Martinez in the leads, both of whom we have praised for their work in other productions. Along with a fantastic set and costumes, plus a live band, it seemed that money was of no object for “Lorenzo.”

Of course we know now that is not enough. And in the case of this musicale, it seemed to be its handicap as well, where the goal of preaching fell into the trap of spectacle, one that was out-of-control and just trying too hard to be cool.

That has to be a mortal sin in some theater bible somewhere. —KG, GMA News

“Lorenzo” was written by Paul A. Dumol and Juan Ekis with Joem Antonio, and was directed by Nonon Padilla. Compositions and musical direction by Ryan Cayabyab. It is a Green Wings Entertainment Network Inc. production, and has shows on September 6 and 7, and September 12-14 at the DLSU-CSB SDA Theater in Malate, Manila.

Katrina Stuart Santiago writes the essay in its various permutations, from pop culture criticism to art reviews, scholarly papers to creative non-fiction, all always and necessarily bound by Third World Philippines, its tragedies and successes, even more so its silences. She blogs at http://www.radikalchick.com. The views expressed in this article are solely her own.

More Videos

Most Popular