Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

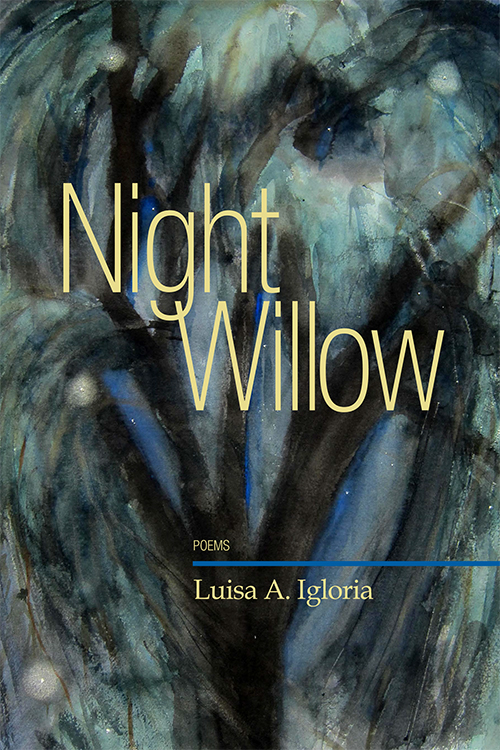

Book review: The poet’s reverent mind in Luisa Igloria’s ‘Night Willow’

By RINA ANGELA CORPUS

Photo from LuisaIgloria.com

This collection of self-reflexive poetic narratives is filled with a descriptive sensitivity and a reverence for one’s being-in-the-world—from furtive glances into emotion-rich imagery, to deeper groundedness into the more diurnal scenarios of life.

Either way, reading Igloria’s new work is a joyful excursion, as if a momentary yet refreshing walk along the shores of a cool ocean, reminding us of the beauty of stepping away from the busyness of a maddening world; and we are suddenly gifted with a much-needed respite from the often tumultuous scenarios in the sea of life.

For what else is the uniqueness of poetry if not its depth, its way of looking inwards closely into the self, and in that way to keenly reflect on how one might really feel for one’s life and the larger world? And what else is prose if not a skilled exposition into life’s moments and imageries? A magical balance between these two—an economy of words and a skillful expansion through the narrative form—is what finds new voice in Igloria’s prose poems.

For instance, take the poet’s quiet acceptance of life as she observes an Oriental movement exercise in the park in “Night Willow”: In their shade, early mornings, an elderly Chinese man came to lead/ T’ai Chi exercises: single whip, warding off, cloud hands, wild horse/ spreading man. Shoes made no sound on the grass.

Her silent watchfulness of this scene then concludes with a tone of surrender to the often unfathomable vicissitudes of life: Dear mystery: daily, night after night, I think you’re testing me. I/ won’t fight with you anymore.

The sign of passing seasons and an awareness of the gifts that they occasion become a point of sudden awakening that brings the author to an attention to what she must wear in “Compass”: Here, on the first warm day/ of spring, I slip on flip-flops and cotton voile. I’ve snipped the/ leather buttons off an old cardigan, saving them for some unknown/ occasion in which I might revive their charm.

Like a lay Buddhist in awe of the simple and natural wonders of life, the poet is in awe of the changing seasons, watching it as if it were a person gracefully changing old skin, signaling newness in life: I read about ascetics and what they chose to renounce. Sometimes I think I want that. Sometimes I want to be both the mountains emerging from their heavy robes of ice and snow, and the stream they feed below, rushing and teeming with color and new life.

In “Blueprint”, meantime, the poet invokes the ancient and numinous mysteries of feng shui to navigate the more practical task of refurbishing of a house: Rooms and hallways must open and close on auspicious spaces, in order not to create voids. Windows must/ open not only to the sun and rain but also to winds of fortune..../In how many languages could we recite th emore than 99 names of God?

But while US-based since the 1990s, we find Igloria still invoking the persistently vivid memories of life in her homeland, as in “In Passing”, where she reminisces, point by point, scenes from her life in the tropics. Here she recalls with fondness the objects of sleeping rituals in the province: She misses nights sleeping under white mosquito netting, the edges tucked around the mattress; the smell of starched, woven cotton.

In “Charmed Life” she also remembers local vegetation and the spirits that her old hometown in the mountains is known for: Where it is coolest under the sayote patch and the bayabas trees.../I want to know; or if, high up in the tress, the spirits watch, waiting to spill their basketful of charms as we pass.

Then there is her reckoning of life as a form of personal heroism in “Index”, as she invokes a vernacular term for “warrior” in her native Ilokano: In old stories, the elders speak of warriors with heart: nakem; of growing wise as growing in heart. Perhaps, what they mean is that capacity not only to survive what gusts in to level us all.

Igloria equally recalls with an astounding sense of detail the yearly folk Catholic devotion for the Black Nazarene in Quiapo, Manila in “Dark Body,” as she names the faceless men that make up the crowd that ardently fulfill their piety for this image of the black Christ: Carpenter, boat-builder, cop and cobbler; plumber, electrician out of work, not yet/ sober tuba-drinker; husband, overseas worker, skirt-chaser, wife-/beater. They’ve all come to touch this visage of coal, this visage of /charred ship lumber...Some have lost a finger, crushed a rib, a clavicle. For miracle, what does it/ matter that one might be trampled?

In a country deeply mired in a of poverty of the spirit, there is a similar undying devotion to a certain saint for the lost as shown in “Santa Milagrita”: The traffic never stops at her wayside shrine: bring me back/ my lover, my daughter, my mother, that life of promised ease. Here, in exchange, all these glittering anatomies: fingers, arms, legs; an eye, an ear – parts we would lop off gladly; if only, if only.

Besides religious themes, Igloria tackles significant historical moments as in “September 1972”, where she reminds us of the beginning of Martial Law. Here, she cleverly threads a rosary of words popularly coined at that time which marked that dark decade in Philippine history: That evening, more rumors. Then radio and TV blackouts, and/ sirens at six and at nine. Not that clarion of the Angelus, but signals/ for the first of many curfews and the squall ahead....At home, in the streets where people cast furtive glances/ at each other, we learned bits of new vocabulary: martial law,/ suspension, writ of habeas corpus/ rally, molotov cocktail, salvage,/ subversive, detain.

Amidst life’s inconsistencies, Igloria makes sense of its disarming grace by paying attention to the munificent signals from the universe, where kindness and its kin virtues continue to throb with life.

In describing the awe-inspiring nightscape in “Landscape, with Things Falling from the Sky”, she puts to fore the unparalleled generosity that she gathers from the sky’s all-encompassing embrace, which is very like the mind of a poet, who is called to develop a more ascendant view of things, in order to bring the world closer to its original sense of reverence for the miracle that life truly is: A galaxy/ is only a dark umbrella someone opens so rain can streak the grass. When all the water’s gone, the ribs shine dull silver. In the spaces far/ between are stars. — VC, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular