ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Philippine children’s literature sees boom in last two years

By MARK ANGELES

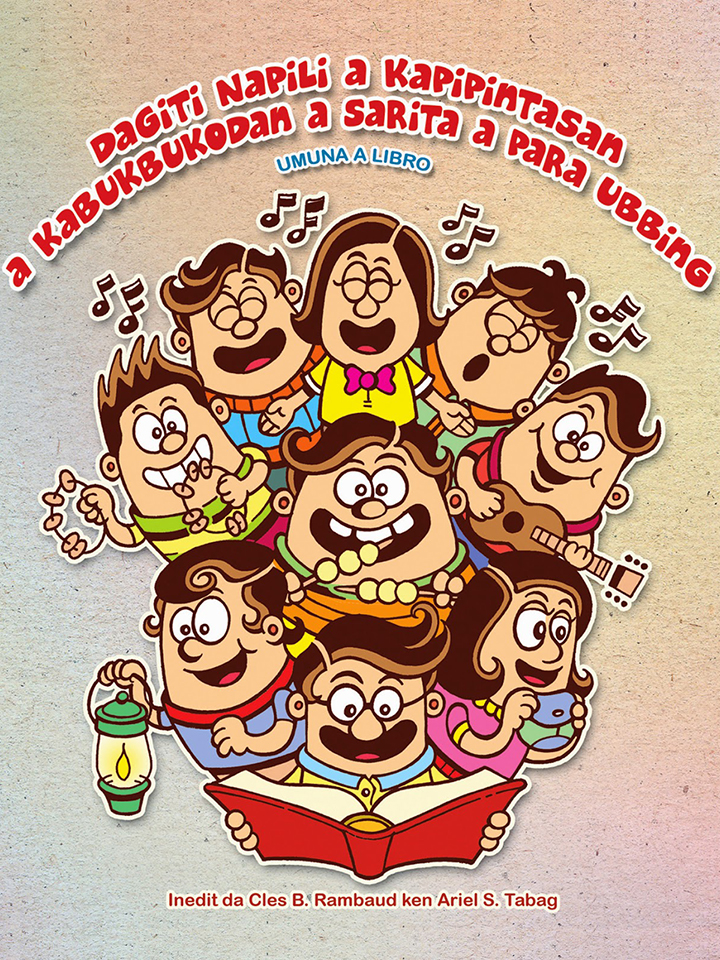

Photo courtesy of Bannawag Magazine

From storybooks to activity books, children’s stories written by Filipino writers are also now available for wider consumption online.

Bonifacio 150

In 2013, the 150th birth anniversary of Andres Bonifacio was celebrated by the Philippine Board on Books for Young People (PBBY) Salanga Prize calling for entries inspired by the life and works of the Supremo.

Michael Jude Tumamac won the grand prize with his story “Ngumiti si Andoy” while honorable mention was given to the author of this piece and April Jade Biglaen for their stories “Si Andoy, Batang Tondo” and “Ang Supremo at ang Kuweba,” respectively.

Tumamac’s story was published by Adarna House during the same year. The storybook, illustrated by Dominic Agsaway, won the 2014 Best Read for Kids Award at the third National Children's Book Awards.

This author’s winning piece is forthcoming under Lampara Books.

Also, Adarna House published the reference books “Ang Pamana ni Andres Bonifacio” by historian Encarnacion Emmanuel and “What Kids Should Know About Andres and the Katipunan” by Weng Cahiles.

Cahiles’s book, illustrated by Isa Natividad, also won the 2014 Best Read for Kids Award.

“Masaya ako na nakapag-ambag sa pagsi-set straight ng history at ng parte ni Boni doon. Lalo na tungkol sa debate sa pagiging unang pangulo nya. Pati na rin sa pagdi-debunk ng myths surrounding him regarding class origin, death, at iba pa,” Cahiles said.

Even the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) saw the impact of children’s literature in the country and jumped in. The November 2013 issue of Ulos, literary journal of ARMAS (Artista at Manunulat ng Sambayanan),the cultural arm of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), included a children’s story “Ang Bagong Alamat ng Bahay-Toro,” written by a certain Maria Catalonan.

Writing the regions

Attesting that children’s literature in the country is not Manila-centric, groups in Northern Luzon and the Visayas contributed their fare share of the harvest.

Just last month, the Ilocano writers association GUMIL Filipinas published the children’s story anthology “Dagiti Napili a Kapipintasan a Kabukbukodan a Sarita a Para Ubbing (Umuna a Libro).”

First of a series, this book collected the best children’s stories which included works by Anna Liza Gaspar (“Ni Anna Sadiay Ili ti Partas-Gasto”), Cles Rambaud (“Ni Ghian ken Dagiti Marmarna iti Bantay”), Godfrey Dancel (“Kukuak La Daytoyen”) , Martin Rochina (“Balay, Balay a Napintas”), and Mighty Rasing (“Ti Gurruod iti Buksit ni Dario”).

It was edited by Bannawag magazine editors Rambaud and Ariel Tabag.

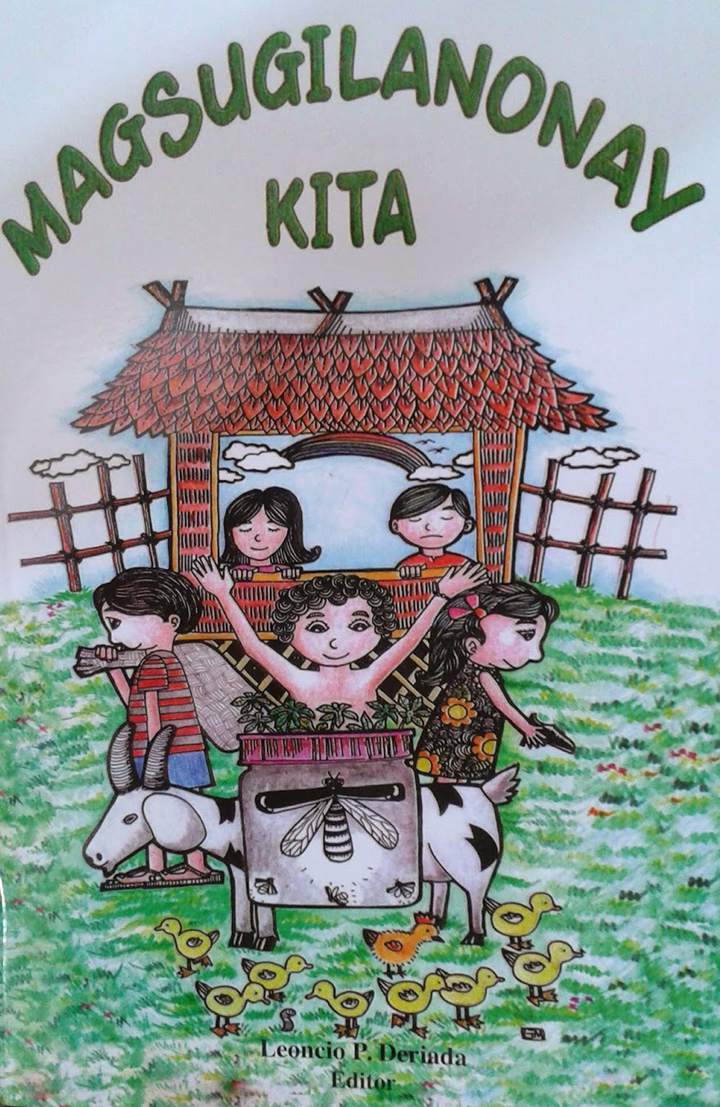

Photo courtesy of Tambubo Hiligaynon

The anthology, edited by Palanca Hall of Famer Leoncio Deriada, included the works of Alice Tan Gonzales (“Si Ani, ang Manugdala sang Kasanag”), John Barrios (“Si Tungko kag si Laon”), Jonny Bernas Pornel (“Gamot”), Dulce Maria Deriada (“Ang Kanding nga si Zebra”), Gil Montinola (“Si Pinay Pinasahi”), Norman Tagudinay Darap (“Igpat”), Eliodora Labos-Dimzon (“Ang Sako ni Mulo”), Agnes Espano-Dimzon (“Abi, Pakta Ninyo”), and Early Sol Gadong (“Ang Paborito nga Duag ni Denden”).

Montinola also did the illustrations.

Barrios published his Akeanon children’s book “Si Kilat ag si Daeugdog,” with a book version in Hiligaynon (“Kilat kag si Dalogdog”). While Balay Sugidanun published Gadong’s Kinaray-a children’s book “Si Bulan, Si Adlaw, kag Si Estrelya.”

And in support of the Department of Education’s mother tongue program, LG&M’s Chikiting Books published a series of dictionaries last year.

The series “Ang Aking Unang Diksiyonaryong Caton” comprises nineteen trilingual illustrated dictionaries including Sambal, Ivatan, Ibanag, Maguindanaon, Hiligaynon, Tausug-Bahasa Sug, Chavacano, Pampanga, Ilokano, Bikol, Pangasinan, Mëranaw, Waray-Waray, Sinugbuanong Binisaya, and Filipino.

Each book also comes with an alphabetical listing of mother tongue words with reverse look-ups in English and Filipino.

In 2013, Adarna House published “Piagsugpatan: Stories of the Mandaya” by Marcy Dans Lee. The first of a series, it was illustrated by the author, together with Conrad Raquel and Aldy Aguirre.

The next year, the company also published the Cebuano big books “Ang Kamatis ni Pilis” and “Ang Buotang Kabaw.”

Lampara Books published the Palanca-winning works “Ang Pangat, ang Lupang Ninuno at ang Ilog,” by Baguio Writers Guild chairperson Luz Maranan and “Ang Magic Bahag” by Cheeno Marlo Sayuno.

Groundbreakers

After receiving rejection from various mainstream publishers because of its lesbian content, Bernadette Neri’s “Ang Ikaklit sa Aming Hardin” finally saw print through independent publishing in 2012.

The story, which won first prize for maikling kuwentong pambata at the Palanca Awards in 2006, was illustrated by CJ de Silva.

In 2013, mainstream has opened its doors to gender sensitivity. Rhandee Garlitos’s “Ang Bonggang-Bonggang Batang Beki,” illustrated by Tokwa Peñaflorida, became a part of the Ginintuang Puso series of LG&M’s Chikiting Books.

Garlitos also wrote the story “Si Faisal at si Farida” to dispel xenophobia against our fellow Muslims.

In 2011, Southern Voices Press published “Jamin: Ang Batang Manggagawa,” written by Jamin Olarita, who at the age of nine became a child laborer at the Sasa port in Davao City. Jamin was eleven years old when she started writing her own story. The storybook was edited by Will Ortiz, Pia Garduce, and Joel Garduce.

In 2014, Eduardo Sarmiento, NDFP peace consultant, launched his book “Susmatanon: Mga Kwentong Pambata,” a compilation of children’s fiction written while in detention at the Philippine National Police (PNP) Custodial Center in Camp Crame.

Innovations in printing also reached the market. Hiyas by OMF Literature, for example, printed Grace Chong’s Palanca winning story “The White Shoes” on Kraft paper, symbolic of shoe boxes.

Flip side: Same plot, same themes

A story from Eduardo Sarmiento's "Susmatanon." Photo from Free ALL Political Prisoners Facebook page

Flip side: Same plot, same themes

Yet, it appears that the greater part of children’s literature churns the same plot and themes.

Madella Santiago, a social worker and chairperson of Salinlahi Alliance for Children's Concerns, shared, “Sadly, most literature for children are products of created illusion. Most children's story books narrate magic, rags to riches and happily ever after stories that teach children to rely and depend on what fate or destiny has to offer.”

She continued, “This created llusion influences children's lives until they become adults. Magic and ever afters do not depict social reality—in fact, they teach us to just accept society as it is and worse, to escape from the ugly reality of worsening poverty experienced by millions of Filipino people.”

This crisis also brought to the fore progressive children's literature, which portrays the real situation of a real world. “This type of literature should be propagated because it teaches us to go back to our roots, love our nation and do something to defend rights of children and communities.” Santiago said.

She explained, “There are storybooks about great leaders of indigenous communities and how they fought those who wanted to steal their ancestral land and other stories that teach morals of unity and collectively taking action—and this should be introduced and taught by parents and teachers to raise children's awareness and help mold them into responsible citizens.” — VC, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular