ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

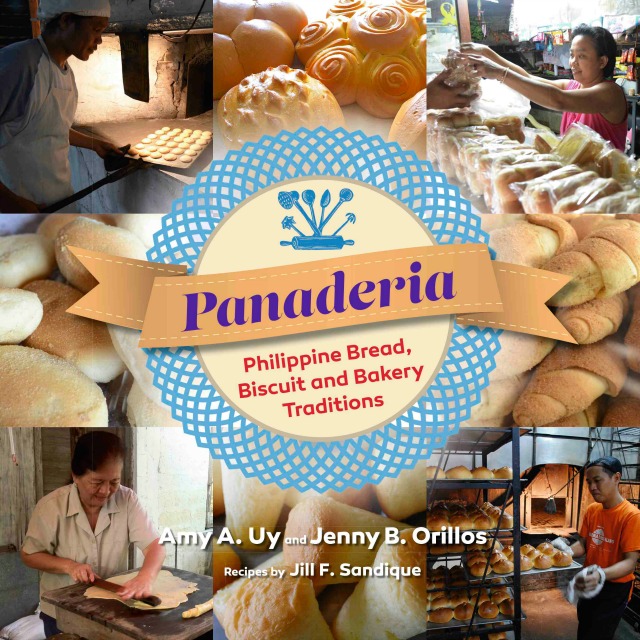

That bread called ‘lipstick’ and so much more in ‘Panaderia’

By KAREN GALARPE, GMA News

'Panaderia' authors Amy Uy and Jenny Orillos traveled all over the country to research their book. In photo: the bakers of United Bakery in Catbalogan, Samar. All photos courtesy of Amy A. Uy

Amy Uy's favorite, meanwhile, is the egg pan de sal, a tiny version of the daily bread we Filipinos love to dunk in kapeng barako or tsokolate eh. “Loaded with egg yolks and margarine, it's so good. I can finish a pack of this is one sitting,” she said, adding it goes well with a slice of kesong puti.

Her other favorite is the Pasuquin biscocho of Pasuquin Bakery in Ilocos Norte, particularly the soft one. “It is pillow-like and has a slightly sweet taste with hints of anise. You can roll out the bread and just spread cheese pimiento on it and roll it back. It's quite a treat, especially with a cold bottle of soda on a very hot day!” she said.

And travel the two did, as they worked over a span of three years documenting the country's many bread products for the book “Panaderia: Philippine Bread, Biscuit and Bakery Traditions.” Name it, they have tried it, from the familiar pugon-baked pan de sal to Batangas' bonete, Iloilo's teren-teren and Cebu's king roll. Then there were the minasa of Bulacan, the masa podrida of Bulacan, Pampanga and Ilocos Sur, and the pan de cana and roscas de Barugo of Leyte. And they discovered there were just so many other baked goodies that are truly Filipino right in our midst.

Here's our bread (and book) talk with Amy and Jenny:

Q: What is the concept of your book? What need does it address?

AMY: “Panaderia” is about the breadmaking traditions of the Philippines. It brings readers inside some of the oldest neighborhood bakeries or “panaderia” around the country to see how they work and what part they have played in the evolution of our bread culture.

JENNY: We have 19 recipes of breads and one on chiffon cake developed by our pastry chef Jill Sandique. The topic is often taken for granted that we don't often see breads as a prism with which we can explore our cultural identity as Filipinos. Many of the breads are vanishing from the panaderia. Even the components of the panaderia like the pugon are no longer being done. We wanted to preserve them at least in the book to remind us of our rich culinary heritage.

Q: How would you assess our Philippine bakery traditions?

The creative team (from left): Book designer Ige Ramos, authors Jenny Orillos and Amy Uy, editor Micky Fenix, and photographer Pie David.

It is something that has become part of who we are as Filipinos, along with the long list of breads that have come out of corner bakeries since the time the Spaniards introduced breadmaking in the country.

We Filipinos have embraced and developed our own bread culture and traditions from baking celebratory breads like ensaymada and torta for special occasions to baking intricately-designed biscuits like the Sanikulas which have ties to our religious beliefs. And then there are the long-observed habits like the “painit” of the Visayans, that of taking something warm such as bread with coffee to calm the stomach or to tide them over till the next meal. Or that of eating bread with noodles like camachile with pancit luglog, binanle with pancit Marilao, pan de agua with lomi, cheese bread with pancit miki, and so on.

There are so many traditions tied to eating different types of breads that we hope can be preserved. Some of them are still very much in place but more so in the provinces than in Manila.

JENNY: Our bakery traditions are still very much thriving thanks to the handful of panaderia that still use the pugon (wood-burning oven). You see, the pugon and the traditional making of breads—especially the pan de sal—is interconnected. Without the pugon, we would have none of the pan de sal with that hint of smoky aroma. Our recipe developer, chef Jill Sandique, said it best: "The breath of the oven from the aroma of the wood burned is imbibed by the bread itself, giving the bread its distinctive flavor."

Likewise, we still have the salty or less sweet pan de sal—just like how our grandparents had them—in some bakeries like in Panaderia ni Pa-a, JBRC Bakery in Iloilo, and a bakery in Digos City. This is the hallmark which we consider traditional, and as long as we still clamor for it, we keep our bakery traditions alive.

Q: Name some of the breads you discovered during the course of doing this book.

The Panaderia Dimas-alang in Pasig, nearly a century old, still uses a pugon.

In Bacolod, there is a similar pairing: pan de siosa, soft plain bread rolls that come stuck together, and is good with the salty and rich Lapaz batchoy.

Also in Batangas, the bonete (bonnet-like bread) is very popular but rendered in various ways across the country. In Cavite, it is called bowling, while in Bulacan it is known as boleng. Some are cone-shaped and soft, others are short and dense, others look like floppy hats. The thing that makes it noteworthy is that it has a savory taste, owing to the use of pork lard.

JENNY: When we were in Pampanga, we were amazed at the different kinds of pan de sal a bakery made there. One was the "regular" one, another was made with pork lard, and a special one they call magapok or crumbly, because the texture is indeed crumbly and a bit dry. It's made almost the same way as regular pan de sal except that it is baked immediately instead of the longer rising time.

Then there's the bonete, which is shaped like a hat; and the king roll of Cebu and Leyte, shaped with the silhouette of a croissant. The Cebu king roll is flavored with anise. There were also a lot of wonderful biscuits like the minasa of Bulacan, pan de cana and roscas de Barugo of Leyte, and the masa podrida which is shaped in different ways in Bulacan, Pampanga and Ilocos Sur.

Q: Do you think we will one day have a certain baked product that will put us in the international arena, like the French baguette, the Austrian croissant, or India's naan bread?

AMY: I'm hoping that that would be the pan de sal as that is probably the most universally favored among our local breads and found in all parts of the country. While eating pan de sal is associated with the "masa", it also graces the dining tables of the middle to upper income classes. Paired with adobo and kesong puti, menudo, chicken galantina, and other fillings, or just a simple spread like margarine, liver spread or peanut butter, the pan de sal is versatile as a snack or as a meal in itself.

However, bakeries would need to go back to the days when pan de sal was the size of a fist and not as sweet and soft as they are today. The standard for making pan de sal must be set and observed just as it is for the French baguette.

A recent issue of Saveur magazine carried a recipe of pan de sal. And that's a hint that among our local breads, it is what best represents the country.

JENNY: We already have the pan de sal that is associated with us internationally. Romy Dorotan of Purple Yam serves it in his restaurant that uses ube flour to give it a whimsical purple tint. He and Amy Besa published a recipe in their book “Memories of Philippine Kitchens.”

Pan de sal has its own unique way of being made so I'm confident it can stand up to its own in terms of baking traditions. We hope what we outlined for pan de sal-making in the book can serve as a guide to the proper way of making it even outside of the country. — BM, GMA News

“Panaderia: Philippine Bread, Biscuit and Bakery Traditions” was launched on May 17, 2015 at Powerbooks in Greenbelt 4 in Makati City. The 264-page softbound book comes with 20 bread recipes done by chef Jill Sandique. The book is published by Anvil Publishing and sells for P595 in National Bookstore and Powerbooks branches.

More Videos

Most Popular