'Let's eat, Lola'

On a recent post on my Facebook page suggesting the strategic addition of a comma to a certain expensively formulated tourism slogan, a cousin of mine made a mischievous comment.

“Let’s eat, Lola.” Then cousin Gina made us imagine omitting the comma, followed by laughing emojis.

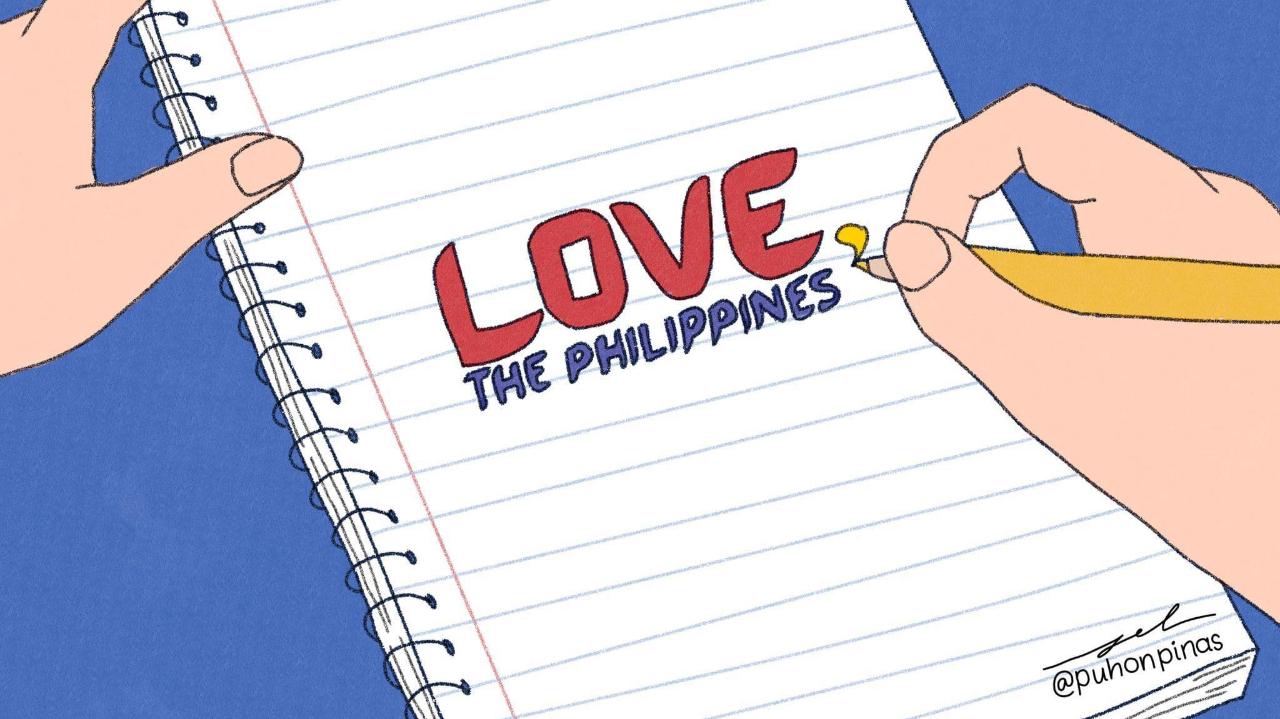

Amid all the reactions to the newly unveiled “Love the Philippines” tagline were some salvos about the underappreciated prince of punctuation, the comma, which I and others have proposed be inserted after the word “Love,” thereby transforming the slogan from what sounds like an imperious order to the tender closing of a letter.

The online crowd has taken over. Like this idea for a graphic someone posted on my page:

“That hurt so good. Keeping memories. Love, the Philippines” — over an image of a tourist getting a traditional tattoo.

A few of my former students in my high school English class nearly 40 years ago chimed in with their own memories of the lessons devoted to the “power of punctuation.” Most took pride in remembering, but the now-50-something class clown Alan couldn’t help but comment, “Kung wala kang punctuation, hindi ka makaka-enrol.”

This unexpected hullabaloo about a possibly game-changing comma made me look for my copy of the best-selling manual on punctuation, “Eats, shoots and leaves,” with a panda on the cover removing the comma. It’s written by the British critic Lynne Truss, who actually once hosted a radio show all about punctuation.

Punctuation for most of us is something we don’t think about unless it’s missing or grossly out of place, like in the title of Lynne Truss’s book. But for writers and their editors, it can be the stuff of feuds. Truss recalls the years-long bickering over commas between the famed writer James Thurber, who hated them, and his esteemed editor Harold Ross, who adored them.

She covers the whole range of functions of commas as the Swiss-army knife of grammar: the comma as both separator and joiner, a bracketing device when used in pairs, and a tool for making lists.

Of course, she also contemplates one of the grammar world’s fault lines, the Oxford comma, as in that last comma in the sentence, “The Philippine flag colors are red, white, blue, and yellow.” Despite the heated argument about its utility, that final comma is optional and a question of style if writing for a publication. The only rule is consistency.

Comma errors are so common, the only predictable thing about commas, it seems, is their unpredictability.

“The fun of commas,” Truss writes, “is the semantic havoc they can create when either wrongly inserted (‘What is this thing called, love?’) or carelessly omitted (‘He shot himself as a child,’ when what is meant is, ‘He shot, himself, as a child.’)”

That takes us back to “Love the Philippines,” which in its current construction was not a mistake. Inserting that abbreviated squiggle after “Love” would not be a huge change graphically. But in meaning, “sea change” might not be too much of an exaggeration. The reactions to the modest proposal already show that it could engage the crowd in creative ways. But then again, retaining the original slogan could also engage any subversive with a sharpie or digital paintbrush intent on adding that small flourish.

Ahh, but hashtags are inhospitable to commas, say naysayers. How do you hashtag a slogan with a comma?!

If you’re in a disruptive mood anyway, one can consider a pilosopo solution: #LovecommathePhilippines. —JCB, GMA Integrated News