Zooming back in time

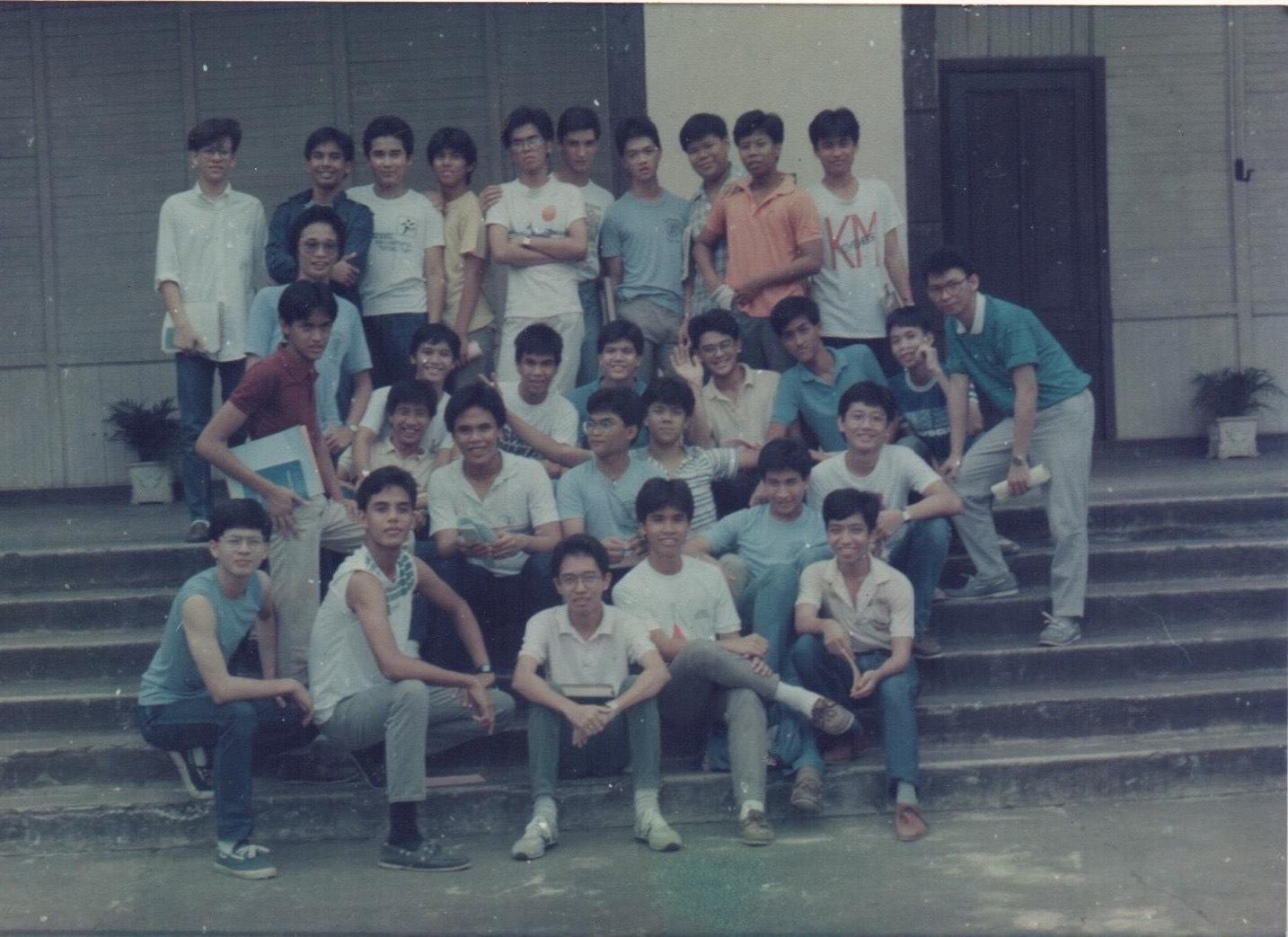

After not seeing most of them for 37 years, I recognized them all, imagining them still seated in front of me without their middle age disguises, fidgeting in chairs that had been built for younger teens.

I was their English teacher in their last year of high school, invited the other day to attend a memorial service on Zoom for their classmate Dindo who died before Christmas in Las Vegas where he had been living for years.

After I popped into the Zoom gallery, the ribbing began about the thousands of vocabulary words I made them memorize in the 10 months I was their mentor-tormentor. I nostalgically quizzed them again on the word “pernicious”; one of them teased a classmate about living out the meaning of “promiscuous,” while a few laughingly remembered that “obnoxious” fit some of them. When one cheekily confessed that he had cheated on a test right under my nose, I played along and threatened to report him to the current Prefect of Discipline, only to be wryly reminded by one of the lawyers in the class of the statute of limitations.

It was a lively moment when we relived our youth, when I was a teacher a year removed from college which they were on the cusp of entering. A few years is a large age gap when you’re that young, but our ages now make us practically of the same generation. The guy named Rookie who was seated in the center row no longer looks like a rookie, not with his salt-and-pepper hair, but his commanding voice was the same one that told his classmates nearly four decades ago to shut up and show me some respect during one rambunctious interlude.

Overall, I told them, they were a respectful, talented bunch who obviously had bright futures. They were also boys becoming men during a turbulent time in the country’s history. I taught them from 1984 to 1985, that crucial, tension-filled period between the assassination of Ninoy Aquino in 1983 and the EDSA revolt in 1986 that drove Marcos from power.

The Ateneo High School is at the end of a long road in a secluded corner of a sprawling, gated campus that also contains the university, residence halls, and the grade school. It was easy to feel insulated in that serene environment from the turmoil in the outside world.

Something happened as they neared graduation that made the stormy world come crashing into their consciousness. For much of the year, few of them knew that their English teacher was living a kind of double life – on our idyllic campus he was trying to be an indio Mr. Chips character, drilling his students on grammar and introducing them to Nick Joaquin; but off campus he was an angry young activist, documenting protest rallies and spending his weekends visiting political prisoners. In January 1985, I was arrested while photographing the violent dispersal of a student barricade. Falsely accused of leading the protest, I ended up in solitary confinement in Fort Bonifacio.

I was finally let out of my cell for a court hearing in Quezon City where I was facing charges of sedition and illegal assembly. As my guards led me out of the van, loud cheers filled the air. I looked up and saw all my students on a long balcony of the court building watching me enter, chanting my name, and making the whole place sound like a varsity basketball game. Their other teachers had allowed them to skip class to give me moral support.

I was released shortly after that when the charges were dismissed, and when I returned to school much of the class time was spent answering questions about my experience and the national situation.

Now as I looked at these guys with grownup children, I belatedly apologized with a laugh for the weeks of absence from teaching that my activism caused. But we all knew that that shared experience helped make their last year of high school a true education in the wider meaning of the word.

Their late classmate Dindo of course was not there to reminisce with us, but maybe he was, as he was the reason we were all there in the first place, his suave photo occasionally flashed on the screen. I told his family he looked much better as a family man than he did as a lanky adolescent.

I was delighted to learn that Dindo (using the name Dean Hernando) went on to a literary career overseas, with three novels and a book of screenplays all sold on Amazon. I need to comb through them, partly to see if he ever used “pernicious” or any of the other words I wrote on the blackboard.