Dining on memory, Part II

Part 2 of 2

Read: Dining on memory, Part I

“Food is political,” Amy Besa declared as we dipped into a salad of radish, mango and carrot slivers just like home but perked by sweetish salt like nothing I’d ever tasted. This was river and sea water blended in a well, three times distilled over fire and purified under the sun the old Zambales way. It was “salt of the earth” as a philosophy you could taste.

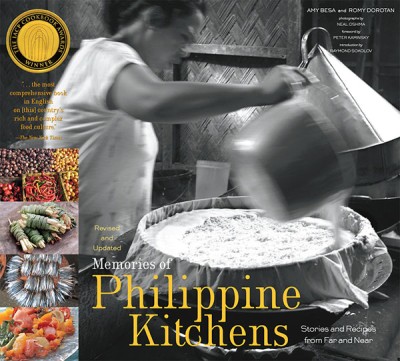

Amy learned this little-known fact along with major insights on the refinements of the ancient Filipino way as she researched for “Memories of Philippine Kitchens.” Long settled in New York—running Cendrillon with Romy Dorotan in SoHo, at home with him in Flatbush—she returned to the Philippines for the first time in 18 years in 1990. Now she would return every four years, finding out more and more about culinary subcultures all over our islands.

Back in New York, Marisa Bulzone, senior editor at Stewart, Tabori & Chang came to visit Cendrillon one day, saying STC was thinking of a Filipino cookbook. She wanted a taste. “But as soon as Romy put a fish sinigang before her, Marisa said she doesn’t eat seafood. So I told her to taste the broth for its essence. Romy and I caucused to see what else we could give her and then when I turned back to ask what she would prefer.

“I was surprised to see that her bowl was EMPTY! She said she loved it,” Amy recalls. Marisa had just discovered Romy’s light touch on seafood, uncannily capturing textures and nuances from ingredients sourced from near and far.

When Marisa brought the president of STC, ready for a deal, New York Magazine had already named Cendrillon the best new Asian resto in 1997. It also counted among New York restaurants known for integrity underlined by Romy’s stint in Alice Waters country with natural food, never ever in cans. With market studies showing the large Filipino population in the US, STC wanted a basic Filipino cookbook with recipes, photos and sidebars.

A contract was signed but Amy, ever the original, “had other ideas.” What luck that Marisa, assigned her editor, “let me do what I wanted.” Possessed by the project, Amy started asking her customers about their heirloom recipes. In typical Pinoy networking genius one thing led to another “virally.”

By 2003, she was happily traveling the islands, pursuing insights from her previous food trips. Feeling like a visiting foreigner welcomed like a homecoming daughter, she found “Filipinos very generous and hospitable. I totally fell in love with my people, culture and food when I was doing this book. Lots of times, I would end up in tears, discovering beautiful undiscovered gems in our culture, especially amongst poor people.”

A gap with her political activist past was closing. “Many rural folk underestimate and undervalue their food and cooking heritage simply because they think they’re ‘poor’ – not much cash flow, unstable livelihoods. What they don’t understand is that they’re rich in natural resources if their environment is still lush and full of plants and animals in forests and fields.”

After two months of travel with photographer Neal Oshima, she brought six shopping bags of interview tapes home to New York. Now she was stumped. Our islands share many tastes but we say it in different tongues! “I could not hire anybody else as some of the interviews were in five languages besides English: Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilonggo, Ilokano, Bicolano.”

She wound up transcribing each and every tape with an interpreter. That took another six months. “My brain was fried after that but it helped. That was how a lot of ideas, concepts and intellectual formulations about the food, culture and history came together.”

It was passion all the way. “Irosin in Sorsogon was particularly emotional for me. Romy could not come; someone had to run the resto. All his food memories he’d been telling me since we met were cooked for us. To actually see and eat all those food memories was really an emotional experience – touching the past, reliving and documenting with photos, interviews and, finally, the book.

“Even more touching, 17 guys cooked. They researched the food themselves. Most of all, the food was a revelation – all delicious yet unknown to the rest of Filipinos. How many know kinagang, tinutungan, pinakro, cassava puto, kinalingking, kinalu-ko? I called Romy that night, weeping. I had totally fallen in love with our food and people in a deeper sense. Nothing could ever top that experience.”

Passion and deepening knowledge rewarded Marisa Bulzone “with a book she considered the crowning glory of her career at STC,” Amy recalls. She wasn’t alone. “Memories” won the Jane Grigson Award for Scholarship and Quality of Writing from the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP).

The first edition in 2006 reached 7th printing; at 2000 copies per printing, that was 14,000 books sold. In 2011, the STC publishing team told Amy their sales department in London advised them to do a second edition. It was one of their reliable bestsellers, defying the normal arc of sales that go down after release.”

Back home National Bookstore struck an exclusive deal with STC, likewise “always listing ‘Memories’ among its bestsellers.” The second edition in 2012, with minor changes like a Purple Yam chapter replacing the chapter on Cendrillon, has 4000 copies sold in bookstores so far. Sales are also brisk in Purple Yam Malate, where diners like me can’t resist its heirloom recipes and their mini-histories.

Amy has reason to be proud: “This was a validation of the goals we set for ourselves – to ‘reimagine’ Filipino food in terms of flavors and ingredients, not in dishes. First we look at what grows in our environment then we taste. If it’s good, we make it into a dish, traditional or reimagined.”

She’s equally proud of her kitchen team – Rap Cristobal, Noah Villaluz, Bryan Tim Ong, Tak Yee Lee, graduates of the College of St. Benilde, all under 24. Their “skills, talent and reinvigorated palate” have rewarded her and Romy’s trust. He guides them from Brooklyn via Facebook.

And so the young run Purple Yam’s new booth at the populist Mall of Asia, as they did in Aura, Global City last Christmas. Many diners who’ve tasted PY’s paninis, baked goodies and ice cream in Malate, Aura and MOA keep coming. It’s magnetic.

When the young at the booth explain Purple Yam’s “food philosophy - natural, homemade, no artificial flavors, preservatives, people are automatically won over. Our ice creams are very popular; they see that it’s pure dairy and fruit - no stabilizers, preservatives, artificial flavorings, food coloring,” says Amy. “Our prices are low. My intention is to hit as many markets we can just to share with as many people as possible the good news that our food is first class, absolutely delicious, at par with any cuisine in the world!”

Amy’s already thinking about her next book with “flavor profiles of the Philippines – geography-based but beyond physical boundaries. I will be chasing a different set of memories – flavors and our palate locked in the deepest recesses of our heirloom rice grains and whatever precious plants and fruits that grow in our environment.”

She uses a French vintner’s word to point to exciting possibilities --“terroir” meaning “the special characteristics that the geography, geology and climate of a place interact with plant genetics, expressed in agricultural plants.”

This she relates to an insight from Filipino scholar Michael Purugganan – the concept of “’cultural preference’ from his study on the evolution of glutinous rice, which he says are not varieties, but mutations of these varieties.

When the early Asians were domesticating rice, they selected only varieties and the mutated ones they LIKED for re-planting. Those they did not care for are gone from our reach. These grains exist today because our forefathers liked them enough to re-plant them for future generations.

“Heirlooms are grains that have basically intact DNA, passed on from one generation to another. What commercial rices we eat are all hybrids. This new book will go beyond rice but rice will be a central point,” Amy says from the center of her world of meaning.

Visions dance of PY’s black paella with heirloom rice – Balatinao and Lasbakan from Benguet, Red Unoy from Ifugao – doused with gata with young eggplants in just the right stage between fresh and boiled, perfect with those fat crab claws and shrimps “still wriggling” that morning.

Then there’s bibingka from the flour of pounded heirloom dinorado grains from Arakan Valley, North Cotabato – and perhaps libations with tapuy made from heirloom rice fermented with that special bubud yeast made by every family for its own brand of tapuy.

Can’t wait for this new feast of food and ancestral memory! — BM, GMA News