I am in Iowa, one of America’s swing states, but there was no need to court me today with robocalls or grim-soundtracked TV commercials or knocks on my apartment door. Not that any of it would have swayed me. I am gay, Fil-Am, mixed-race, twenty-eight, and a woman — the kind of voter a certain party, carrying the majority of the older white vote, might snort at and dismiss outright. No matter. I had already voted at the local Iowa City mall two weeks before, thanks to some well-organized, calm, early voting efforts in Iowa over the past month. If it doesn’t make sense to Filipinos that, regardless of the popular vote, the entire United States hones in on ballots cast in rural counties in Iowa and Ohio and Florida every four years—? Well. It doesn’t make sense to many Americans either. It is, crudely put, an attempt at balance and fairness: the votes of the popular masses are tempered by elected presidential electors, state by state. It is an imperfect system, as the two-party Democratic/Republican system is imperfect. I wouldn’t be surprised if both became open to revision within my lifetime. There were reports of voting irregularities in the swing states: poor, elderly black American voters told to go home for a piece of paperwork, the troubling use of provisional ballots in Ohio, electronic machines gone oddly haywire in favor of Mitt Romney. The UN thought voter fraud in the United States to be likely and troubling enough to send election monitors, which made some states feel nationalistically prickly. But with the dream of a better Philippines somewhere in my daily yearning, as it is for so many Fil-Ams here, I am conscious of what was absent in the United States today. There were no politicians brazenly offering cash, t-shirts, or favors in poor neighborhood for votes—though some might argue that American corporate donations to campaigns are equally corrupt. There will be no months-long wait for ballot results, the votes left to be tampered with or bought in the interim delay. The elected president is not the member of a century-old political dynasty or oligarchy; he is the mixed-race child of a modest family, and he required loans to attend university. Like I am, and I did. There were no horrifying massacres. There was no politician’s backhoe. Today I walked to two polling places nearby in Iowa: one was a sleepy center for senior citizens, and the other was the University of Iowa library. I saw no one harassed. I saw no beggars. I saw no huge lines, though they were present in New York, Ohio, Florida, and elsewhere. I saw no one’s vote refused. I saw no one with weapons. There appeared to be no need for weapons.

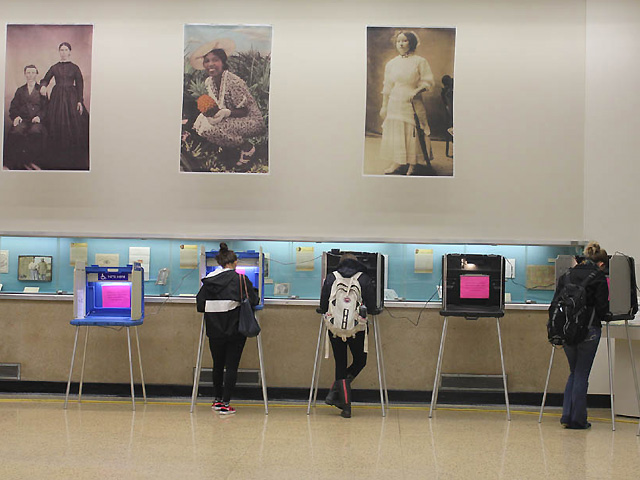

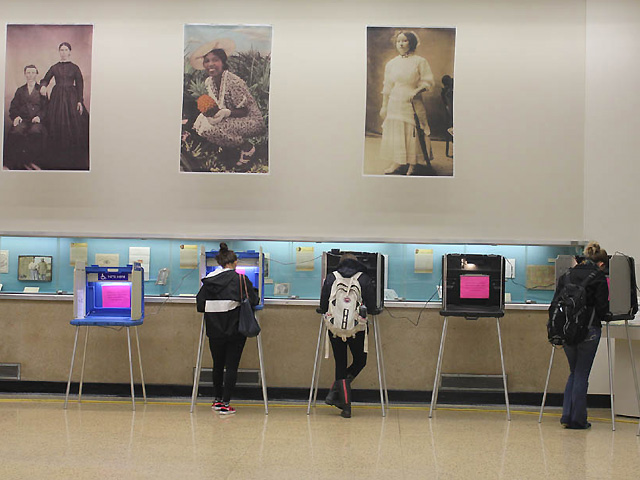

Women vote at the University of Iowa library. Above them is a library an exhibit called 'Pathways to Iowa: Migration Stories from the Iowa Women's Archives.' Laurel Fantauzzo

If my hardworking white father taught me anything about United States culture, it is this: Americans insist on self-sufficiency and efficiency, or the dream of efficiency. There is a shut-up-and-get-it-done-

yourself-ness, an insistence on clarity and quickness in the States psyche,

pakikisama be damned, that can make Americans seem bullying and impatient to Filipinos. But in the context of America, Americans often benefit. So merely hours after voting, nearly a hundred Iowans gather in a bar near the University of Iowa to hear the election results. The audience members—largely young white students—do not behave like the denizens of a divided swing state. They cheer unabashedly for Obama, for a Democratic Senate, for gay and lesbian rights, for the legalization of marijuana, and for women candidates. When CNN calls the election for Obama, they rise to their feet, scream, cheer, clap, and begin to order a drink specially called the O-Bomb. (There is no drink specially named after Mitt Romney). In the other parts of the country marked solidly red, other bars might be more grim, more filled with anger at the diverse country that re-elected the mixed-race American president, legalized marijuana in Colorado, and elected the first openly gay lesbian senator in Wisconsin. There are many Americas within America, just as there are many Philippines within the Philippines. But when they wake tomorrow, our citizens, Democrats or no, will be secure in their peaceful transfer of power. We anticipate no violent, attempted coup. Americans—comfortably oblivious to their historical role in violently shaping the Philippines for the most part—may spend their entire lives without living a developing nation’s troubling, civic evolution. But the Philippines will never be oblivious of America, and I don’t think that constant consciousness will change in my lifetime. From my lifelines to the motherland—my Facebook and Twitter feeds—I can see that my friends in the Philippines, are, for the most part, happy and relieved with America today. Gay and lesbian advocates in Quezon City wept with relief. “Bye, Mitt!” said my friend the Ateneo history professor. “Congrats, America, for not failing us!” said my friend the novelist who lives near Taft Avenue. “O” one friend typed happily, and simply. I scroll and scroll through my friends’ overseas commentary, while Iowans cheer and drink beside me. I’ll walk home from this bar’s huge CNN screen relieved that the country of my birth and citizenship is still capable of peaceful, democratic changes in government. When I step over the wet fliers on my doorstep and sleep in my apartment in Iowa, though, I don’t think I’ll feel quite at peace. I think I’ll dream of my hopeful friends in the archipelago. I think I’ll still yearn for my mother’s homeland, and the peace and order and equality it still pursues, and still deserves.

- GMA News