ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Topstories

News

It’s time to reconsider privatization in the PHL

By RICHARD JAVAD HEYDARIAN

Amid the uproar over Meralco’s proposed electricity price hike, it is increasingly clear how the Philippine government is hardly in a position to credibly supervise the power sector. Though I previously dedicated a piece to the macroeconomic implications of the electricity conundrum in the Philippines, I never considered the magnitude of our regulatory crisis.

Richard Javad Heydarian

In many ways, it seems that the government has barely sought to effectively prevent any potential intra-industry collusion in one of the most crucial pillars of our economy.

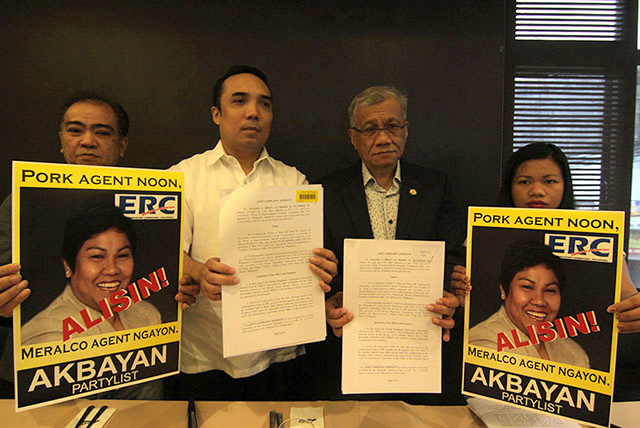

Recently, Zenaida Ducut, the head of the Philippine Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC), told an investigating panel in the Philippine Congress how her agency is hopelessly “undermanned”, whereby, quite shockingly, “insofar as our [electricity] spot market division is concerned, we [ERC] only have 4 personnel under our plantilla." Leaving a handful of bureaucrats to oversee the complex operations of the Wholesale Electricity Spot Market (WESM) is arguably tantamount to outright regulatory negligence.

No wonder, Ducut is forwarding a quite untenable argument that the ERC could not be held accountable for any potential collusion with the power industry players, since in the first place her agency was hardly even in a position to fully determine the legality of existing market operations.

Widespread regulatory deficit

Such blatant absence of credible supervision could very well be extended to other major industries, which were privatized in recent decades. For instance, critics have raised concerns over the oil industry, which has been dominated by a handful of major suppliers in recent years. More specifically, there is a concern over how the government seems to lack any direct means of cross-examining big companies’ price-determination mechanisms.

While price fluctuations in the global oil markets are generally used as a basis to justify corresponding increases in domestic petrol prices, critics claim that big companies have hardly subjected their accounting procedures to direct state supervision. Thus, there is no way for us to definitively ascertain the validity of any price adjustments.

After all, it is common knowledge among energy analysts that distributors don’t solely rely on spot markets for their supply, since future markets and storage facilities, among others things, allow industry players to hedge their bets against short-time price fluctuations in the global energy markets.

This means that the Philippines has effectively transferred to big private companies the control of two critical sectors, electricity and oil, without necessarily ensuring a modicum of regulatory supervision. The heavily privatized water sector is not short of its own critics, too. It is precisely for this reason that the Philippines should reconsider the wisdom of privatization, especially when there are no guarantees for the effective establishment of corresponding regulatory agencies.

There is nothing inherently wrong with market participation in the provision of goods and services, particularly when you have a long legacy of public mismanagement. Add to this the debt crisis that griped the post-EDSA Philippines, paving the way for a transition towards a market-oriented economy.

The perils of privatization

The 1990s, especially under the Ramos administration, saw a concerted effort at streamlining the state bureaucracy. The aim was to transform the Philippine state from a “social” state, one that is concerned with the provision of basic welfare to all citizens, to a “watchman” state, which is primarily focused on securing property rights and ensuring the smooth operation of markets.

Subsequently, state-owned enterprises were privatized, trade barriers were dramatically reduced, and the private sector was bequeathed with the responsibility to provide basic services such as power and water. The government also withdrew from the oil industry, allowing putative market forces to take over. The aim of the privatization schemes was to ensure efficiency (in supply) and affordability (in access) of public goods.

Soon, the government confined itself to palliative welfare schemes such as the Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) program. Relatively cheap to administer and increasingly popular, CCTs have become a centerpiece of 21st century welfare across much of Latin America. And other developing regions such as Asia have followed suit.

The problem, however, is that the privatization of public services has indubitably failed to deliver. Massive power shortages have put into question the supposed efficiency-gains of private sector ownership. With the Philippines having one of the most expensive electricity and oil prices in Asia, accessibility is obviously a major issue -- especially for electoral democracies such as ours.

Towards a “third way” governance

Exorbitant electricity costs – coupled with weak infrastructure – have (and continue to) discouraged greenfield investments from abroad. The CCT schemes, meanwhile, have allowed many developing countries, including the Philippines, to justify stagnant investments in critical sectors such as health and education, which have historically proven to be central to poverty-alleviation and the empowerment of the middle classes.

So, what are we to make of this?

It is important for the government to augment its regulatory institutions to ensure already-privatized sectors are abiding by the rule of law. But beyond that, as Congressman Walden Bello recently told me, what we need the most is to “encourage both partnership and a balance between government and the private sector, with checks on both by the civil society via the institutionalization of surveillance and consultation mechanisms."

If the Philippines seeks a credible shot at climbing the development ladder, we should profoundly reconsider our recent economic policies. What we need is nothing short of regulatory soul-searching and ensuring our entrepreneurial classes are given enough space to institute real market competition.

Richard Javad Heydarian teaches International Political Economy at Ateneo De Manila University (ADMU), and is a columnist for Huffington Post and Asia Times. He is the author of "How Capitalism Failed the Arab World: The Economic Roots and Precarious Future of the Arab Uprisings" (Zed, London). He can be reached at jrheydarian@gmail.com

More Videos

Most Popular