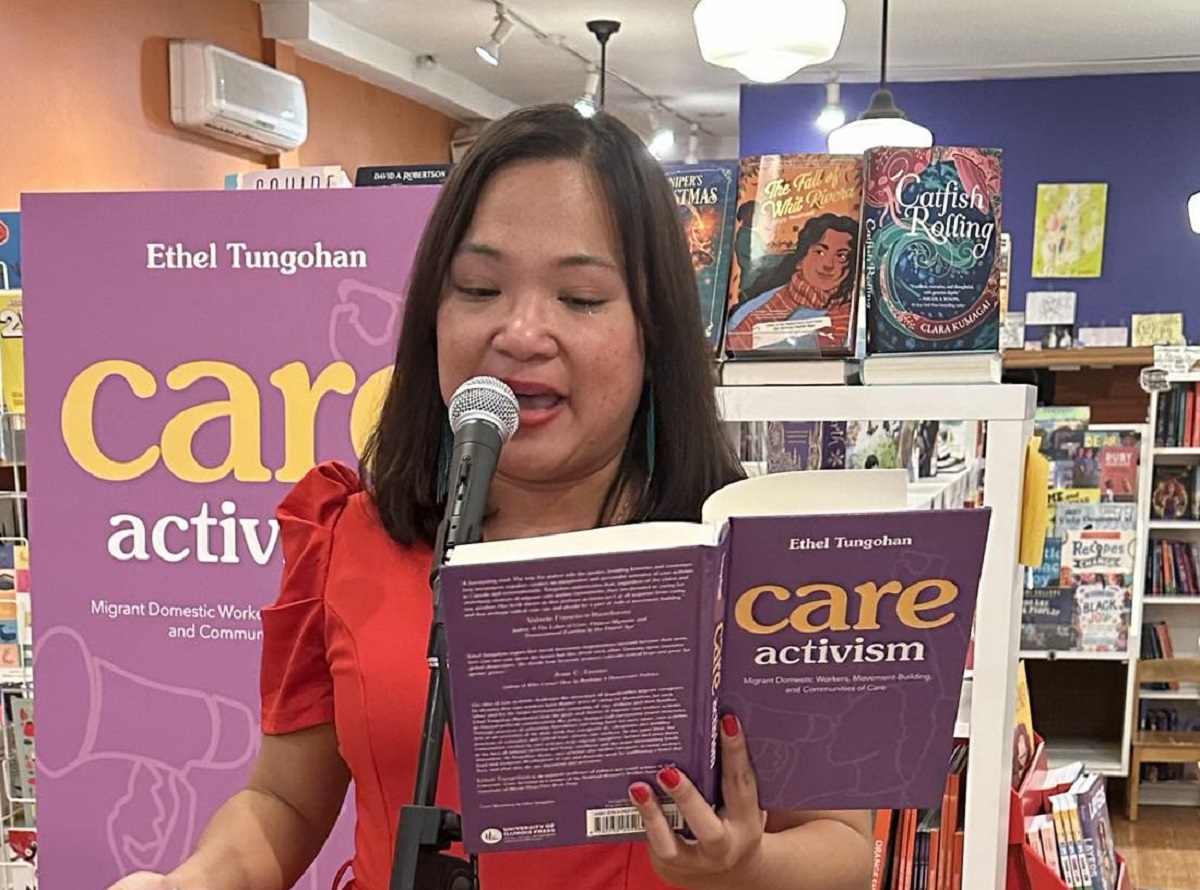

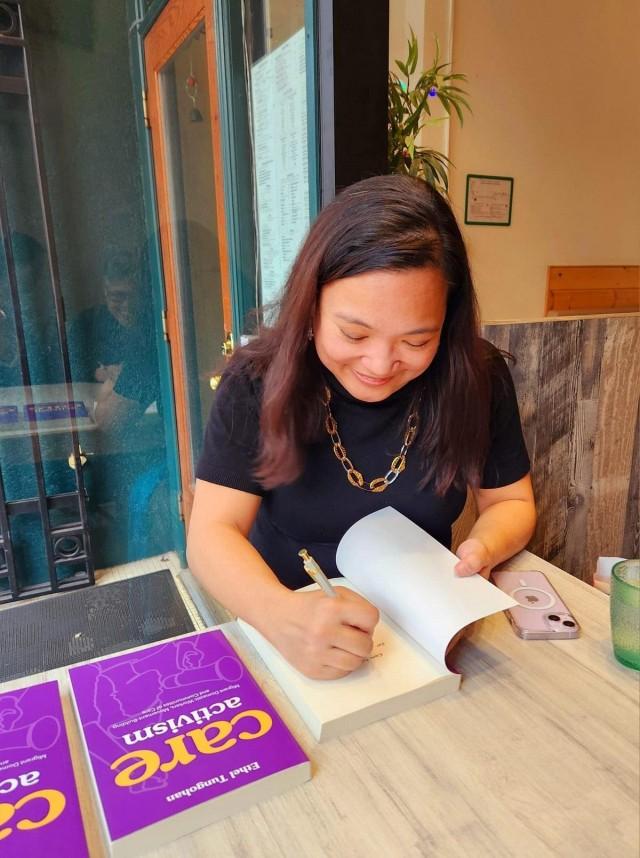

Fil-Canadian educator tackles caregivers' struggles in book

RED DEER, Alberta — Instead of despair and tragedy depicted by the mainstream media, caregivers' engagement in changing their plight is the centerpiece of a new book by esteemed Filipina-Canadian educator Prof. Ethel Tungohan.

Titled “Care Activism: Migrant Domestic Workers, Movement-Building, and Communities of Care,” the book, published in August 2023 by University of Illinois Press, tackles how care activists and migrant domestic workers’ movement in Canada play a key role in ushering important policy changes to meet the sector’s needs.

Rights advocates said the book also recognizes the often “invisible and undervalued” labor performed by migrant domestic workers.

Friendships, support

Tungohan, whose family immigrated to Canada from the Philippines in 1999, serves as the Canada Research Chair in Canadian Immigration Policy, Impacts and Activism at York University in Toronto, Ontario. She is also an Associate Professor of Politics at the university.

“It started as part of my PhD dissertation. After I won the 2014 National Women’s Studies Association First Book Prize, I received a book contract and started turning my dissertation into a book, which ended up becoming a love letter of sorts to migrant domestic worker activists and their families,” said Tungohan in an email interview with GMA News Online.

In Hong Kong where she resided before coming to Canada, Tungohan witnessed how friendships among caregivers created spaces that allowed them to support and uplift each other.

“They provided support for each other in ways that states like Canada and the Philippines and even other organizations cannot or will not,” a piece that was missing in the narratives surrounding domestic work, she said.

“As my book shows, it was actually migrant domestic workers who were behind key policies, such as the ability for caregivers to apply for Canadian citizenship. Prior to migrant domestic workers’ activism, migrant domestic workers were only given temporary contracts,” she added.

Policy changes

It took Tungohan a lengthy 12 years — from 2009 to 2021 — to complete her dissertation and later turn it into a book. The challenge during this time span was that policy changes pertaining to care work in Canada also kept occurring.

“In 2013, for example, there was a vitriolic response to the presence of temporary foreign workers in Canada, that led to the Live-in Caregiver Program being replaced by the Caregiver Program,” she explained.

“Since then, various ‘pilot’ programs have been passed. So keeping up to date with policies, and tracking how care activists responded, was a challenge,” she added.

In 2019, the federal government’s Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) came up with two new pilot programs for caregivers looking for work in Canada. The five-year programs, namely Home Child Care Provider Pilot and the Home Support Worker Pilot, which allowed caregivers and their family members to come to Canada, are set to expire in June 2024.

Also in February 2023, IRCC reduced the work-hour requirement for caregivers to apply for permanent residence from 24 months to 12 months of full-time work. This change was expected to impact 90% of PR applications in process.

On top of the policy changes within Canada, Tungohan also had to adopt in her book the changes in the political arena here and abroad.

“There were also momentous political upheavals taking place: the defeat of the Conservatives in Canada, the election of the Liberals, the election of Trump, the election of Duterte, the election of Bongbong Marcos, and COVID. I had to keep updating the book to reflect these changes. That meant having to rewrite parts of the book and revisit different arguments,” Tungohan said.

In completing her dissertation, Tungohan used “ethnographic research,” immersing herself in various migrant domestic worker communities.

Her research brought her across Canada, Philippines, Singapore, Hong Kong and in Geneva during the deliberations on the creation of a Convention on Domestic Work.

She also conducted some 136 one-on-one interviews with migrant domestic worker activists and attended countless events.

Resistance

Besides taking to the streets to protest, little acts of resistance that Tungohan called “micro-rebellions” were exercised by caregivers to resist their living and working conditions.

Strategies such as using humor and beauty pageants to quietly fight back against abusive employers and an indifferent policy landscape captured the creativity of domestic workers in finding ways to resist, noted Tungohan, an observation shared by migrant rights advocate Leny Rose Simbre, who lives in Toronto and chair of Migrante Ontario.

“[The] book sheds light on the often unnoticed labor of migrant domestic workers, emphasizing its pivotal role in the care economy,” Simbre said, adding that the book offers a resource for migrant justice advocates looking for a starting point.

“It underscores the importance of legislative reforms and labor protections to ensure fair treatment and working conditions for this vulnerable group,” she said.

For Tungohan, the work of care activists continues. When the federal government reviews its two pilot programs for caregivers before the June 17 deadline, the sector will require support from the community, she said.

“It is very important that our community support the campaign of coalitions such as the Migrants Rights Network, and ask for status upon arrival for caregivers as well as lobby for stronger labor protections,” said the mother of two girls. —KBK, GMA Integrated News