ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Scitech

SciTech

New kind of magnetism revealed in 'Herbersmithite' rock

By SHAIRA F. PANELA, GMA News

It is green, blue green, and emerald green, brittle, glassy, and magnetic, much to the surprise of scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Unlike the two known types of magnetism ferromagnetism and antiferromagnetism, this weird rock called herbertsmithite demonstrates a "fundamentally new kind of magnetic behavior."

The rock is named after--you guessed it --Dr. Herbert Smith, mineralogist from the National History Museum, London, England.

Ferromagnetism is the more popular type of magnetism; think bar magnets, and compass needles. The other one, antiferromagnetism, is when the poles of two different matter cancel each other out; check out the red head of your computer's hard disk.

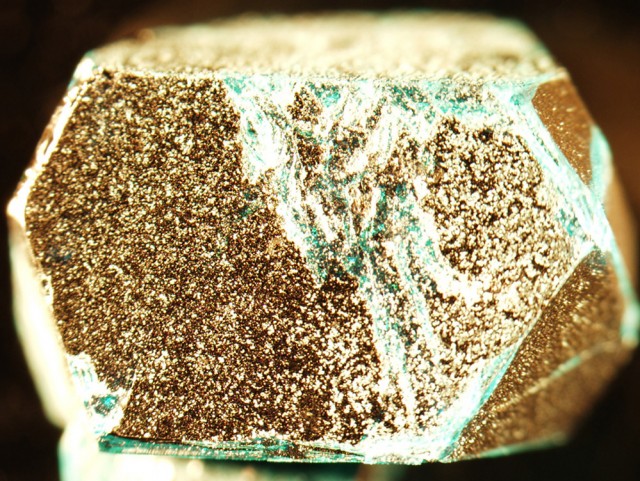

MIT physicists grew this pure crystal of herbertsmithite in their laboratory. This sample, which took 10 months to grow, is 7 mm long (just over a quarter-inch) and weighs 0.2 grams. (Tianheng Han)

“We’re showing that there is a third fundamental state for magnetism,” MIT physics professor Young Lee told "MIT News."

In Dec. 20 issue of the journal Nature, Lee and his team's study "Fractionalized excitations in the spin-liquid state of a kagome-lattice antiferromagnet," proved the existence of a new state called "quantum spin liquid" (QSL) where "spooky" fluctuations (as per Einstein's opinion of QSL) prevent the spin order of electrons.

It is really a solid crystal but its magnetic state is "liquid."

It is really a solid crystal but its magnetic state is "liquid."

Magnetism is a result of a specific order of movements of electrons within atoms called spin. Electrons usually align to form a pattern. But QSL materials are rather peculiar.

"Rather than aligning in a stable, repetitive up-down pattern as they do in most magnetic solids at low temperatures, the electrons in a spin liquid are frustrated by mutual interactions from settling into a permanent alignment, so the electron spins constantly change direction, even at temperatures close to absolute zero," the "Science Daily" reported.

“Tthere is a strong interaction between them, and due to quantum effects, they don’t lock in place,” Lee told "MIT News."

To come out with this result, Lee and his team had to grow a tiny herbertsmithite for 10 months, and analyze it through firing beams of neutrons at it.

With much difficulty, the MIT scientists were able to prove that herbertsmithite is indeed a QSL.

"This is one of the strongest experimental data sets out there that [does] this. What used to just be in theorists’ models is a real physical system," Lee said.

Theories about QSL's existence have been known since Philip Anderson proposed it in 1987, but there hasn't been enough evidence to prove it until MIT's breakthrough study.

“That’s a fundamental theoretical prediction for spin liquids that we are seeing in a clear and detailed way for the first time," Lee said.

However, Lee believes that it would still require a long time before this research can be put to practical use.

"MIT News" reported that this "very fundamental research" can lead to advances in communication or data storage. But he cautioned that “We have to get a more comprehensive understanding of the big picture.”

“There is no theory that describes everything that we’re seeing," Lee concluded. – KDM, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular