Filtered By: Scitech

SciTech

Whale poop shapes marine ecosystems

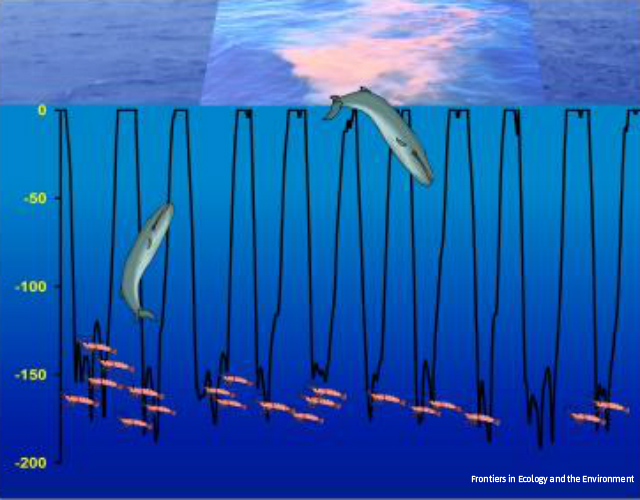

Huge blue whales plunge to 500 feet or deeper and feed on tiny krill. Then they return to the surface—and poop. This 'whale pump' provides many nutrients, in the form of feces, to support plankton growth. It's one of many examples of how whales maintain the health of oceans described in a new scientific paper by the University of Vermont's Joe Roman and nine other whale biologists from around the globe.

Scientists are finding out that with great poop comes great responsibility.

Great whales, despite their enormous sizes, have been hunted to such small numbers and are so difficult to study that their impact on the marine environment has largely been overlooked—until now.

Great whales, despite their enormous sizes, have been hunted to such small numbers and are so difficult to study that their impact on the marine environment has largely been overlooked—until now.

After tallying and consolidating several decades of research, an international team of scientists has concluded that the great whales are in fact "marine ecosystem engineers" with large impacts on marine ecology through their effects on nutrient transfer via their poop and urine and carbon inputs when their carcasses sink to the deep sea.

The great whales also influence the ocean's physical engineering when they plow through sediments in search of food and the ocean's food web interactions because they are both predator and prey. The team is composed of scientists from the University of Vermont, University of California-Santa Cruz, M Expertise Marine, University of Hawaii (Manoa and Honolulu), Harvard University, University of Tasmania, University of Maine, Gulf of Maine Research Institute, and Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research.

The "great whales", a group that includes the biggest animals to have ever lived (yes, some of them are bigger than dinosaurs), include all of the baleen whales (suborder Mysticeti) and the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus).

These whales feed on fish, krill, plankton, and squid at depth then return to surface waters where they poop and pee. This "whale pump" delivers nitrogen and iron to waters that are nutrient-limited, triggering an increase in algal growth. More algae means more food for other animals. The whales also transfer nutrients from their high-latitude, high-nutrient feeding grounds to their low-latitude, low-nutrient calving grounds. Whales typically fast during the calving period.

Whale carcasses are also so big, there are deep sea animals that specialize in living on whale carcasses. When whale carcasses sink to the deep ocean, they provide a massive pulse of carbon, protein, and fats to an area that is typically nutrient-poor. These "whale falls" also provide habitats for the different animals that live there. A distinct ecological succession takes place, first with scavenging animals like sharks and hagfishes eating the soft tissues, then other animals taking advantage of the nutrient-rich sediments, then the bacteria decomposing the remaining skeleton.

However, commercial whaling has drastically reduced the populations of great whales worldwide by at least 66% and total whale biomass by an estimated 85%. The numbers for many species are even more extreme: current populations of blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) are only 1% of their historical numbers. "This decline has likely altered the structure and function of the oceans," says lead author Joe Roman.

Great whales make big targets and predators like the killer whale (Orcinus orca) take advantage. But with the decline in great whales, killer whales shifted to smaller animals such as seals, sea lions, and sea otters. With the loss of sea otters came an increase in their sea urchin prey, and these sea urchins devastated coastal kelp forests.

The loss of kelp led to a decrease in coastal fish populations. With the loss of the whales also came the decrease in the "great whale conveyor belt" of nutrients and whale falls.

"Our models show that the earliest human-caused extinctions in the sea may have been whale fall invertebrates, species that evolved and adapted to whale falls," Roman said. "These species would have disappeared before we had a chance to discover them."

The loss of kelp led to a decrease in coastal fish populations. With the loss of the whales also came the decrease in the "great whale conveyor belt" of nutrients and whale falls.

"Our models show that the earliest human-caused extinctions in the sea may have been whale fall invertebrates, species that evolved and adapted to whale falls," Roman said. "These species would have disappeared before we had a chance to discover them."

But all is not lost. With the ban on commercial whaling, the recovery of some great whale populations is underway. "The continued recovery of great whales may help to buffer marine ecosystems from destabilizing stresses," the team of scientists writes.

"As long-lived species, they enhance the predictability and stability of marine ecosystems," Roman said. Marine ecosystems are threatened by climate change, which includes increased ocean temperatures and ocean acidification. — TJD, GMA News

"As long-lived species, they enhance the predictability and stability of marine ecosystems," Roman said. Marine ecosystems are threatened by climate change, which includes increased ocean temperatures and ocean acidification. — TJD, GMA News

Macy Añonuevo earned her MS Marine Science degree from the University of the Philippines. She is a published science and travel writer and was a finalist in the 2013 World Responsible Tourism Awards under the Best Photography for Responsible Tourism category. Her writings and photographs may be found at www.theislandergirl.com.

More Videos

Most Popular