ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Scitech

SciTech

This blood-sucking Jurassic parasite is straight out of 'Star Wars'

By MIKAEL ANGELO FRANCISCO

Now here’s something you don’t see every day—come to think of it, it’s actually something the world hasn’t seen in about 165 million years: an ectoparasitic insect that can scare the jetpack off Boba Fett himself.

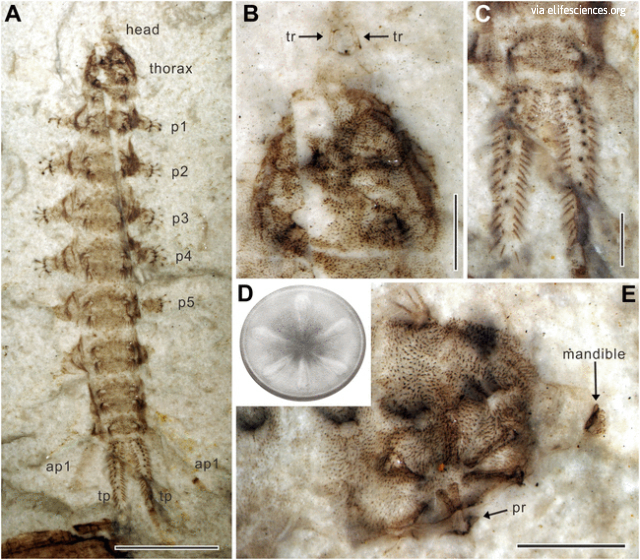

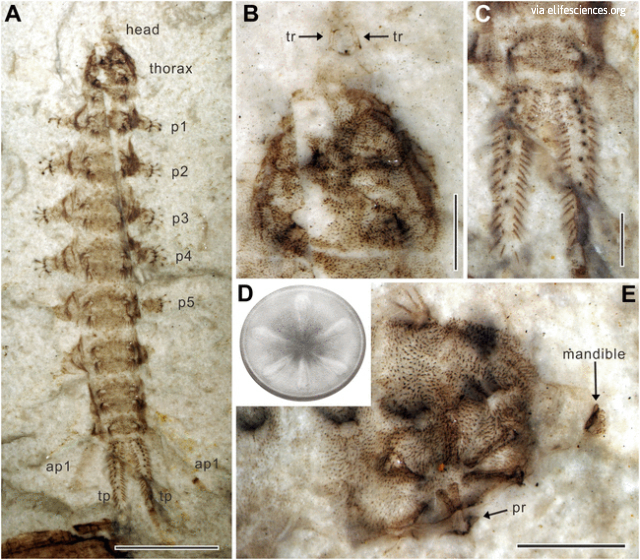

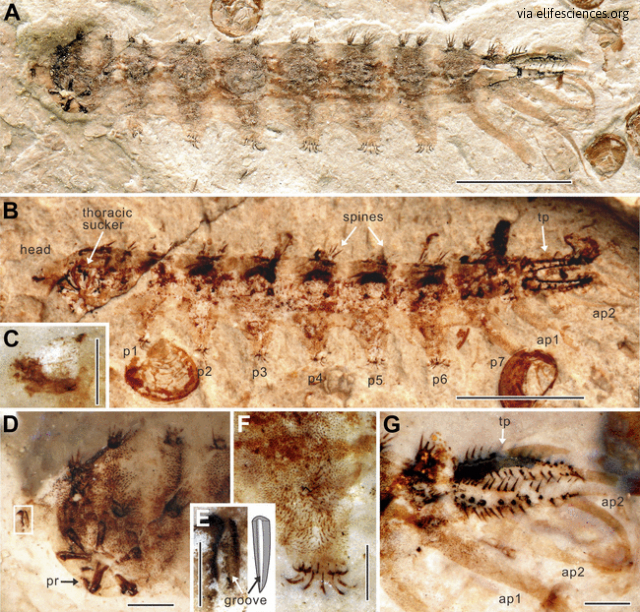

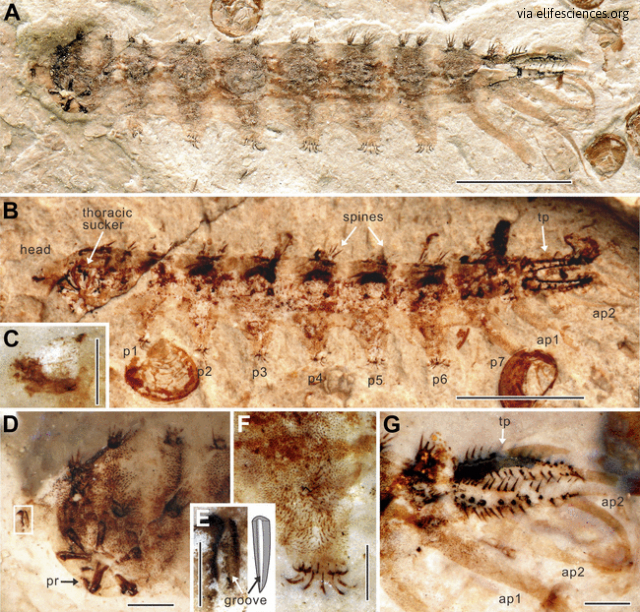

Qiyia jurassica, named after the Chinese word for “bizaare” and the geologic time period the fossil belonged to, was a parasitic larva that dwelled in the freshwater lakes of what would eventually become Inner Mongolia. This two-centimeter terror feasted upon passing salamanders, sucking the blood out of the amphibians through an anatomy reminiscent of the fearsome Sarlacc from the “Star Wars” films.

A small, segmented, salamander-sticking sucker

A team of international researchers from the University of Bonn in Germany, the Linyi University and the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology in China, the USA’s University of Kansas, and the Natural History Museum in London, England published a paper in the journal eLife, discussing their findings in further detail.

Though it did not really bury itself in underwater sands and wait for prey to fall into its mouth, the underside of Qiyia jurassica’s thorax (mid-body) somewhat resembled a Sarlacc pit, with a circular sucking plate and mouthparts built to pierce the thin skin under salamanders’ gills (where plenty of blood vessels tend to be located). It also had a relatively tiny head, and its abdomen (hind-body) was segmented and had legs like a caterpillar’s.

"No insect exists today with a comparable body shape", says Dr. Bo Wang, co-author of the study and a researcher from the University of Bonn.

Saved by the mudstone

Recently, thousands of fossilized salamanders, as well as about 300,000 “diverse and exceptionally preserved” insect fossils, were discovered in Middle Jurassic Daohugou beds near Ningcheng, China. While Dr. Wang affirms that fossilized salamander finds were virtually “unlimited,” no fossil fish were found in these Jurassic-era freshwater lakes. The absence of predatory fish most likely allowed the fly larvae to thrive.

"The extreme adaptations in the design of Qiyia jurassica show the extent to which organisms can specialise in the course of evolution", says Prof. Jes Rust, who hails from the University of Bonn’s Steinmann Institute.

As a result of the fine-grained mudstone where the creatures lay for millions of years, the fossils of the ectoparasitic larvae were preserved remarkably well. “The finer the sediment, the better the details are reproduced in the fossils,” explains Dr Torsten Wappler, study co-author from the Steinmann Institute. Additionally, the conditions in the groundwater prevented bacteria from thoroughly decomposing the fossils.

However, the scientists currently do not have enough data to picture what Qiyia jurassica would have looked like after metamorphosing into its adult stage, or to speculate about how it could have lived and survived as a full-grown insect.

Suckers, not killers

According to the researchers, the parasites probably did not kill the salamanders through their parasitic activities. As Dr Wappler illustrates, "a parasite only sometimes kills its host when it has achieved its goal, for example, reproduction or feeding.”

Still, one can’t help but wonder if the conversations between victimized Jurassic salamanders who survived brushes with Qiyia jurassica sounded like this:

— TJD, GMA News

Tags: starwars, qiyiajurassica

More Videos

Most Popular