ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Scitech

SciTech

These dinosaur-era crabs were just 'eyeballs with legs'

By MIKAEL ANGELO FRANCISCO

Here’s a "crabby" carnivore you really wouldn’t want to anger, lest he unleash a whole lot of prehistoric weirdness upon you.

Around 435 million years ago, Thylacares brandonensis swam through the seas of the Silurian period, hunting prey with short, spiny limbs and crushing them before devouring them. Named after the Brandon Bridge Formation near Waukesha, Wisconsin where it was found, T. brandonensis is the oldest known ancestor of the thylacocephalans, an extinct species of mysterious and rather bizarre-looking sea creatures from the Jurassic period.

Claw (grand)daddy

Findings on the newly discovered species were recently published in BMC Evolutionary Biology. “This new research extends the range of this enigmatic group of fossil arthropods back to the Silurian, some 435 million years ago, and provides evidence that they belong among the crustaceans, the modern group that includes lobsters, shrimps and crabs,” says Derek Briggs, G. Evelyn Hutchinson Professor of Geology and Geophysics at Yale University and study co-author.

Because of thylacocephalans’ strange morphology – a large, nearly full-body carapace resembling a shield, a trunk only visible from the rear, bulbous compound eyes, and long appendages for hunting – scientists were unsure as to how to classify the members of the Thylacocephala group. This led to the creatures, which had been extinct for 84 million years, being mistakenly identified as shrimp larvae or barnacles.

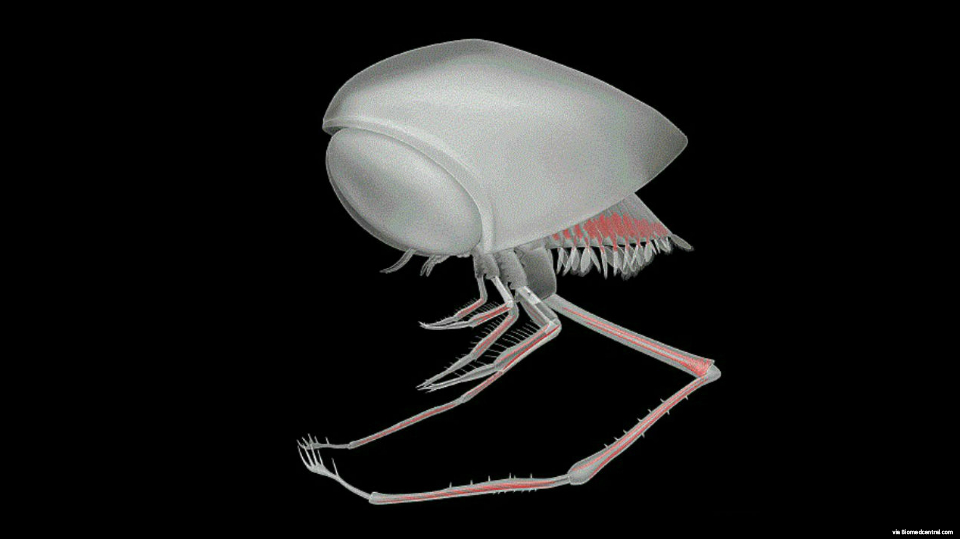

The unique morphology of thylacocephalans is perhaps best reflected in Clausocaris lithographica (pictured below), a 150-million-year-old thylacocephalan from the Jurassic period. Discovered in Solnhofen, Germany, C. lithographica has been described by researchers as an “eyeball with legs” due to its rather odd physical features.

These strange features led experts to conclude that thylacocephalans were predators that either took an active role as mobile hunters or employed stealth tactics to ambush and reel in their prey – behavior that researchers believe T. brandonensis exhibited as well.

"T. brandonensis was probably an actively hunting predator, which caught the prey with its front claws and crushed it into smaller pieces with the protrusions nearer its mouthparts,” according to Carolin Haug, a research associate from the University of Munich and co-author of the paper.

"This early, Silurian, example of Thylacocephala is in many ways much less extreme than the more recent Jurassic species,” explains Haug. “It still has normal-sized eyes in contrast to the very enlarged ones that came later, and shorter front claws in T. brandonensis compared to the extremely elongated ones in more recent Jurassic representatives."

Krill-ing any doubt

Thanks to state-of-the-art imaging techniques, scientists were able to reconstruct T. brandonensis’ muscular structure in 3D. Indeed, T. brandonensis’ morphology appears to be a primitive version of later thylacocephalans’, suggesting that their one-of-a-kind body structure – different from virtually any other arthropod – evolved further over time.

Moreover, the spines found on the fossilized appendages match those found on many crustaceans, strengthening the possible link between thylacocephalans and today’s crabs, shrimps, and lobsters.

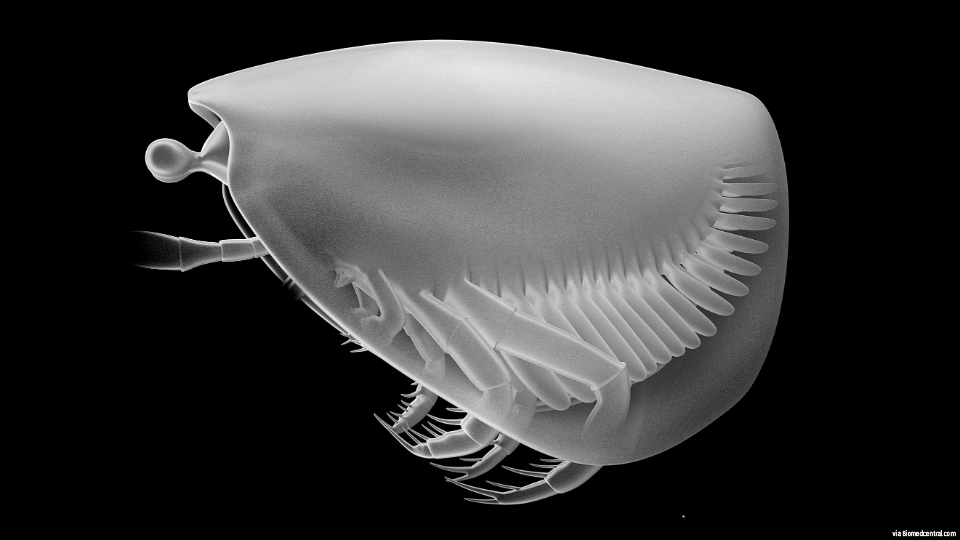

Interestingly, T. brandonensis’ appendages and muscle structure also lend credence to the theory that thylacocephalans constitute a “sister group” to Remipedia, sightless crustaceans that reside in saltwater-filled caves and resemble millipedes (such as Speleonectes tanumekes, pictured above).

Meanwhile, the rest of the world can finally stop wondering if thylacocephalans were actually born out of the unholy union of a Beholder and a Martian Tripod. — TJD, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular