ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Scitech

SciTech

50-legged marine predator is ancient ancestor of flies, centipedes

By MICHAEL LOGARTA

Paleontologists have unearthed fossils of an ancient arthropod species that provides revelations about the genesis of Mandibulata – the most abundant and diverse animal group that includes ants, flies, centipedes, and crayfish.

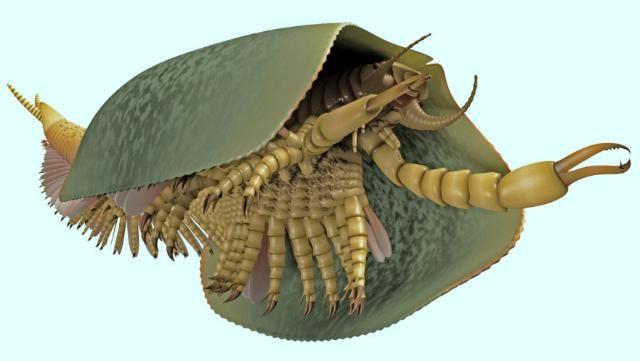

The arthropod species, known as Tokummia katalepsis, was discovered in the fossil deposit of Canada’s Marble Canyon in Burgress Shale, British Colombia. This large bivalved creature sheds light on early mandibulates’ anatomy.

“In spite of their colossal diversity today, the origin of mandibulates had largely remained a mystery,” stated Cédric Aria, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at China’s Nanjing Institute for Geology and Palaeontology.

“Before now we’ve had only sparse hints at what the first arthropods with mandibles could have looked like, and no idea of what could have been the other key characteristics that triggered the unrivaled diversification of that group.”

Tokummia katalepsis lived some 508 million years ago in the Cambrian period.

The animal made its home in tropical seas. Like today’s mantis shrimps or lobsters, it was a bottom-dweller. Measuring over 10cm (3 inches) long, it was also one of the Cambrian Explosion’s largest predators.

“This spectacular new predator, one of the largest and best preserved soft-bodied arthropods from Marble Canyon, joins the ranks of many unusual marine creatures that lived during the Cambrian Explosion, a period of rapid evolutionary change starting about half a billion years ago when most major animal groups first emerged in the fossil record,” explained Jean-Bernard Caron, a study co-author, University of Toronto associate professor, and Royal Ontario Museum invertebrate paleontology senior curator.

Body structure

After extensive examination of the fossil specimens, the researchers discovered that the Tokummia katalepsis boasts large serrated mandibles. It also has maxillipeds – specialized forward claws commonly found on modern mandibulates.

“The pincers of Tokummia katalepsis are large, yet also delicate and complex, reminding us of the shape of a can opener, with their couple of terminal teeth on one claw, and the other claw being curved towards them,” said Aria.

“But we think they might have been too fragile to be handling shelly animals, and might have been better adapted to the capture of sizable soft prey items, perhaps hiding away in mud.”

He added: “Once torn apart by the spiny limb bases under the trunk, the mandibles would have served as a revolutionary tool to cut the flesh into small, easily digestible pieces.”

The Tokummia katalepsis’ body consists of over 50 segments, all of them protected by a bivalved carapace – a wide, two-piece structure resembling a shell. This segmentation calls to mind myriapods, a group of animals consisting of millipedes, centipedes, and other such creatures.

“Tokummia katalepsis also lacks the typical second antenna found in crustaceans, which illustrates a very surprising convergence with such terrestrial mandibulates,” said Aria.

The creature also has subdivided limb bases featuring small projections known as endites, which are present in the larvae form of a number of modern crustaceans. Scientists today think these structures served as significant evolutionary innovations where mandibulates’ many legs, and the mandibles themselves, are concerned.

These fossils share similarities with those uncovered over a hundred years ago at Burgess Shale.

“Our study suggests that a number of other Burgess Shale fossils such as Branchiocaris, Canadaspis and Odaraia form with Tokummia katalepsis a group of crustacean-like arthropods that we can now place at the base of all mandibulates,” Aria stated.

The study was published in the journal Nature. — TJD, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular