It has been High Crimes and Misdemeanors Week. Of late it’s been difficult to find a Pinoy in the news that can be proudly held as a role model for kids. Last week, when you got to watch TV, you were assailed by the news of generals and their wives caught with their hands in the cookie jar, so to speak. No wonder then our ill-equipped foot soldiers couldn’t find Commander Bravo in Mindanao, the AFP fat-cats have taken their money and high-tailed it to Moscow. But some say the P9 million is on budget and a lawful cash allotment for official uses and departments and all that, etcetera etcetera. I know, but no matter how you cook it, it still smells rotten though. Next week promises more desultory tales of malfeasance with a former undersecretary who had fled abroad to avoid prickly questions about allegations over another money scam. This man seemed determined not to spend another winter in a US jail so he’s decided to come home to soak up our beautiful sunshine (some senators have promised instead to have him raked over the coals). Where’s a role model when you need one? Thank goodness then that TIME Magazine was found one beacon of hope—a single bright spot in the current crop of dubious Pinoy celebrities. TIME has hailed scientist Dr. Jurgenne Primavera as one of its “Heroes of the Environment in 2008.†It’s good to see a person who’s done something productive lauded for her life’s work. While TIME did a bang-up job with her story and how she’s trying to strike a balance between saving mangroves and the demands of tiger-prawn farming (shrimp farms destroy a big chunk of the country’s remaining mangroves), TIME didn’t mention Dr. Primavera’s excellent handbook on Philippine mangrove species.

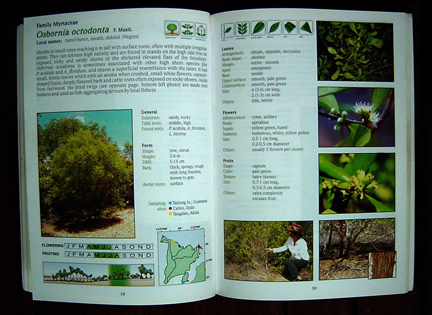

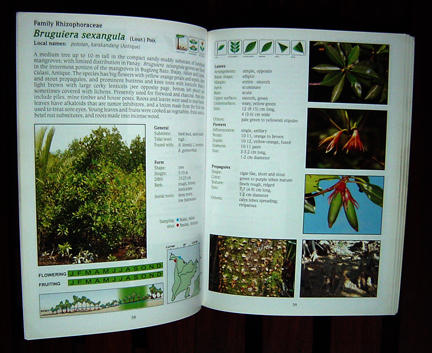

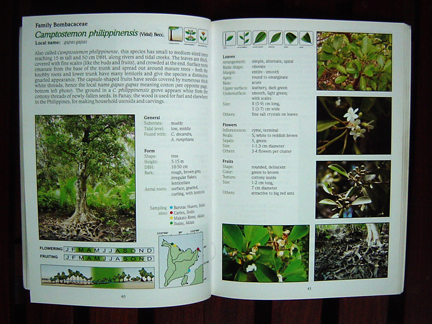

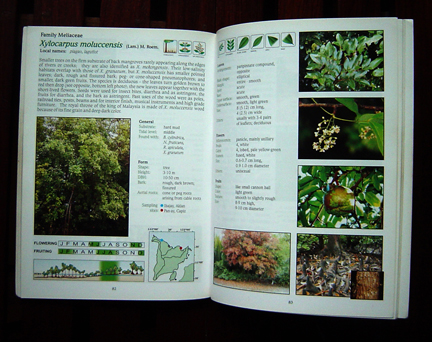

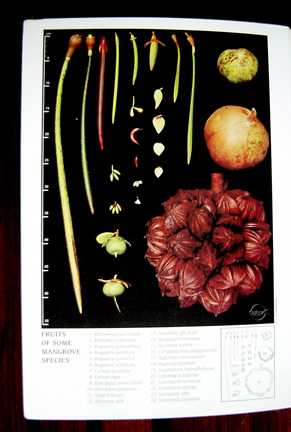

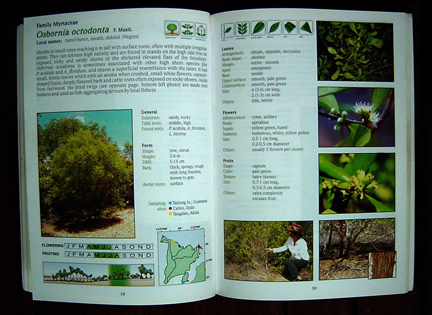

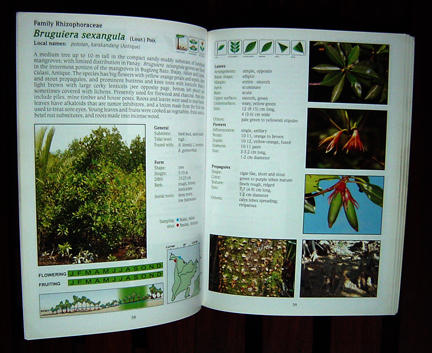

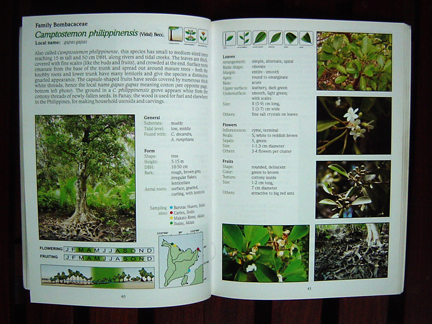

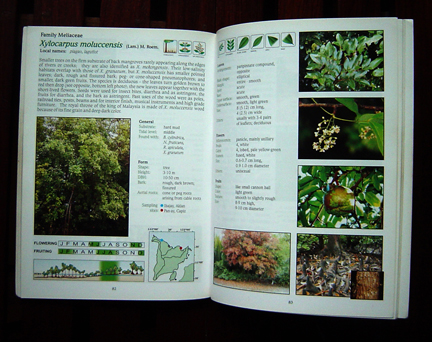

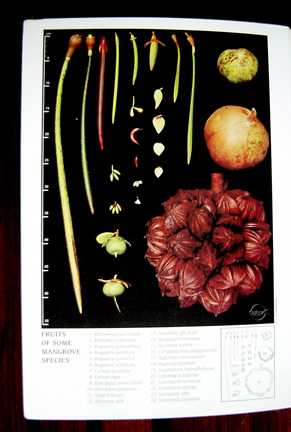

Published in 2004 by UNESCO, Dr. Primavera etal.’s “Handbook of Mangroves in the Philippines – Panay†is a product of more than a decade of fieldwork by the doctor and her collaborators Resurrecion B. Sadaba, Ma. Junemie H.L. Lebata and Jon P. Altamirano. Despite the “Panay†in the title, one can use this handbook to identify mangrove species anywhere in the Philippines and in Southeast Asia. Ah, mangroves. The under-appreciated and hard-to-understand sister of the marine ecosystems family. They’re so hard to understand and appreciate that we are bulldozing them wholesale to make way for shrimp and fish farms (shrimp cocktails are easier to appreciate). Compared to the glamorous and oh-so-chic coral reefs with their supermodel denizens of Disney and Pixar appeal, mangroves are like Ugly Betty—they are no eye-candy but they do have a quirky appeal for geeks. Everyone wants to save Little Nemo and his cute little anemone house in the coral reefs, but what of the yucky worms that live inside mangrove stands? Don’t they deserve the same care and protection (and TV time) given their coral-living cousins? It’s easy to say yes when you’re staring at your monitor at home feeling righteous indignation, but try saying yes when a sumptuous lemon-grilled tiger-prawn cocktail is dripping sweet-chili lime sauce right in front of your eyes and you’ll realize the decision is not so clear-cut.. Are we willing to destroy our few remaining mangroves so the fat-cats among us can enjoy more spicy shrimp cocktails with spiced pistachio chutney? Dr. Primavera says there’s a middle way; to save both mangroves and maintain a steady supply of tiger prawns. There’s no getting around the fact that mangroves are muddy, smelly and full of mosquitoes. But they do have an important function in nature. We have heard about how mangroves act as a buffer to prevent effluents from reaching the coral reefs. Or how mangroves act as a nursery for many marine and terrestrial animals. Or how mangroves help lessen coastal erosion. Or how supermodel Petra Nemcova was saved by a mangrove tree she clung to during the great tsunami a few years back. Or was that a coconut tree Nemcova hung on to?

It’s weird but there’s a saying about galaxies that remind me about mangroves:

Galaxies are like people: the better you get to know them, the more peculiar they often seem. The same is true about mangroves: They get more interesting the better you know them. Manila got its name from

Scyphiphora hydrophyllacea, also known as nilad in Tagalog and

sagasa,

bolaling, or

hanbulali in Ilonggo. This mangrove species was said to be so abundant along Manila Bay and the Pasig River in pre-Hispanic times that the natives, according to lore, called the area “May-nilad.†Imagine if the Spanish explorers who landed on the mouth of Pasig had asked an Ilonggo-speaking trader who happened to be in Manila at the time. Maybe instead of “Metro Manila†we would have had “Metro Ma-Sagasaâ€? “Metro Ma-Bolalingâ€? It must be noted, too, that there are historians who dispute that this mangrove’s local name was ever nilad. Interestingly, nila is from the Sanskrit for “indigo tree†(where this trivia leaves us, I have no idea, but it’s interesting for “Jeopardy Nights.â€)

But what I learned after reading Dr. Primavera’s very interesting field guide, “Handbook of Mangroves in the Philippines – Panay†is that the pre-Hispanic

balanghai which was discovered in Agusan del Norte was made from mangrove wood called

dungon. This mangrove species has wood so strong, waterproofed and salt-tolerant that it was used to make bridges, cart axles, ships, and entire wharves. As someone who usually sees mangrove plants as knee-high saplings during mangrove tree-planting press releases, this was a revelation. Mangroves big enough to make ships! According to Dr. Primavera, various kinds of mangrove trees including

pototan,

bantigi,

bungalon and

piagao were known by early Pinoys for their strength and were used to make houses, rice mortars and pestles.

Pototan or

busain were used to make foundation pilings, house posts, flooring and cabinet work.

Pototan was the source of the popular dark-red dye used for fish nets, ropes and sails. According to Dr. Primavera’s book, the Malaysian king’s throne is made from a mangrove wood known as

piagao known for its “fine grain and deep-dark color.â€

A mangrove wood called

kawilan, was a favorite for carvers of knife handles in some areas in the Philippines. Another,

pagatpat, was a popular wood to make musical instruments. Curiously, there is a local bird also called

pagatpat whose noisy and grating call can politely be described as “nonmusical.†A kind of

bungalon was highly prized for firewood because it produces new branches quickly after cutting. The smoke of its dried branches acts as mosquito repellant and its leaves can be fed to livestock.

Bungalon was also valuable to traditional salt makers: its ashes were used to line a funnel through which seawater was poured. The resulting filtrate was sun-dried to produce salt. The original

taku of Efren “Bata†Reyes, was said to be made of a kind of tough mangrove wood,

bakhaw (which is also the catchall name for all mangrove trees) which, when it was still abundant in the Philippines was the preferred timber for railroad ties, mine posts, beams and joists.

The powdered bark or

baluk of special mangrove trees is the source of the traditional dye that gives

tuba its dark-red color.

Tungog (also known as

tangal and

tagasa) reportedly gave the best

baluk powder used in making

tuba,

bahalina and

basi. If the preferred

tungog baluk was not available, then other mangrove bark—

bakhaw baluk—can be used as substitute to prepare

tuba. I suppose if you could taste the difference, then you’re a true

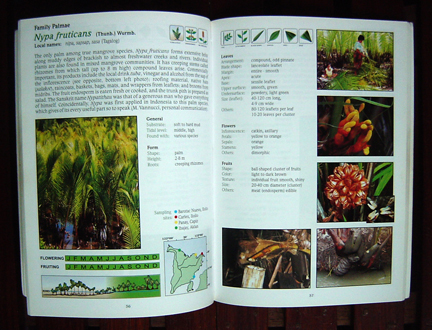

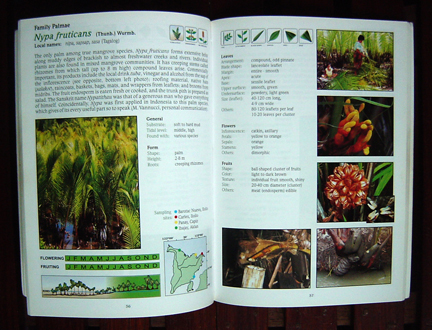

tuba connoisseur? Dr. Primavera’s book is a field guide to mangroves but the trivia parts are fascinating. Take for instance the facts about Nypa fruticans also known as

nipa,

sapsap and

sasa.

According to the ever-interesting Dr. Primavera, the word Nypatithau comes from Sanskrit which means “a man who gives everything.†No kidding, this remarkable mangrove plant literally gives everything of itself to people. Its uses include: roofing material, baskets, bags, hats, brooms, mats, vinegar and alcohol. The inside of its fruit, as well as its pith, is edible. One can imagine this plant, after giving itself to help humans (sniff sniff), asking “What more do you want?†as the bulldozers cut it down to make way for shrimp farms.

So if you can find Dr. Primavera’s Handbook, it would be a nice addition to a collection about Pinoy marine life, next to Genevieve Broad’s “Fishes of the Philippines,†Alan White’s “Philippine Coral Reefs, A Natural History Guide,†and Gutsy Tuason and Eduardo Cu Unjieng’s “Anilao.†Unless you seriously plan to identify mangroves in the wild, I suppose this handbook has a very limited practical use, but it’s cool that such a book exists anyway. It’ll probably make a nice present for that geeky teenager who dreams of becoming a marine biologist. If you know of any other uses of mangrove wood and plant parts, post them here.