I have no emotional investment in the US presidential race. My interest in this contest rests mainly in the pop cultural references made by late-night punch lines and parodies—the punking of Sarah Palin by a fake Nicolas Sarkozy, the Saturday Night Live skits, The Daily Show send-ups and the comments in the Huffington Post. The specific issues that weigh on the mind of the American voter have nothing to do with me. Right now I am far more concerned about the intricacies of HSM3 (that’s “High School Musical 3â€) so that I can explain to my nephews where I stand on the issue of Zac Efron’s hair. When HSM2 came out and I could not name the East High School’s basketball team my nephews expressed doubt over my ability and judgment to be an effective uncle. But a short stay in Baler, Aurora Province, has given me occasion to revisit and re-think Barack Obama’s positioning of himself as the agent of a “Change You Can Trust.â€

Obama’s soaring rhetoric about changing the world—repudiating the Cheney-Bush legacy—is inspiring legions of Americans who’ve grown tired (and poorer) after eight years of Cheney-Bush. On the eve of election Obama told a crowd of supporters that they are “on the verge of a new era†as the fired-up audience yelled back, “We Want Change!†Is this a good thing for us? Does Obama’s promise of a more humane America extend to us who continually have to suffer the fallout of US foreign policy decisions? Or is it a hollow promise, based on the same ideology that the US has pursued for the last hundred years beginning when it built itself into the world’s leading industrialized nation? What has our history taught us?

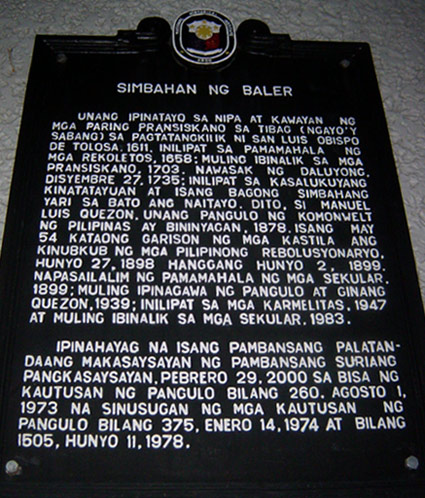

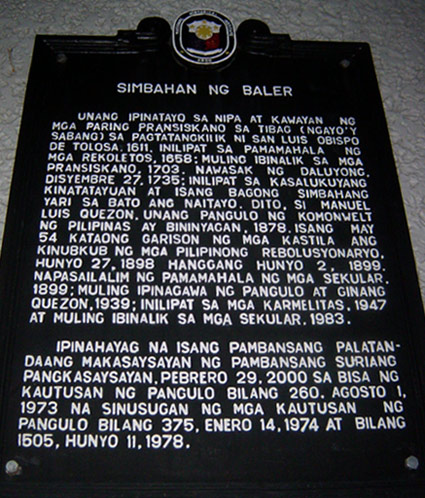

In the town square of Baler stands the unassuming Baler Church. Its stone façade doesn’t call attention to itself; the visitor’s gaze, in fact, is drawn more towards the well-landscaped Manuel Luis Quezon monument next to the church where a bronze statue of local boy Manuel sits comfortable and firm in his faith in the Pinoys’ ability to govern themselves—a belief we may not share in our more cynical moments—but that is why Quezon was a visionary and I am a grown man watching a (hit!) Disney musical. Despite its plain appearance, the Baler Church has a colorful story: It was the last piece of Philippine territory held by the Spanish empire. A commemorative plaque traces the church’s history back to 1611, and in one sentence sums up the historic Siege of Baler which signaled a momentous event in world history—the fall of the once-mighty Spanish empire and the rise of a brash, young American one:

“…Isang may 54 kataong garison ng mga Kastila ang kinubkob ng mga Pilipinong rebolusyonaryo, Hunyo 27, 1898 hanggang Hunyo 2, 1899…†

The Siege of Baler lasted an incredible 11 months, with the 54-man Spanish force barricaded inside the church surrounded by about 800 Filipino militiamen. Unknown to the isolated Spanish, forces under Emilio Aguinaldo and the Katipunan had taken possession of most of the Philippines, except for Manila whose entry points the Americans controlled after Commodore George Dewey’s Manila Bay victory in May 1, 1898. The Spanish stragglers in Baler dug in and waited for the nonexistent reinforcements to arrive. In spite of efforts by the Filipinos to inform the holed-up Spanish that their empire has quit the islands, the poor, bewildered soldiers did not believe them and hung on, wracked by diseases and hunger. Meanwhile, skirmishes occurred between Filipino and American forces in and around Manila as the Spanish empire limped away and Filipino insurgents became increasingly suspicious of American motives. Heated debates erupted in the US Senate between the anti-imperialists and those who viewed the annexation of the “uncivilized†Philippines as a God-given duty (“The White Man’s Burdenâ€). One of the two senators who opposed the Treaty of Paris was a Republican named George Frisbie Hoar who argued: “This Treaty will make us a vulgar, commonplace empire, controlling subject races and vassal states, in which one class must forever rule and other classes must forever obey.†On the opposing side an imperialist senator, Knute Nelson of Minnesota was quoted as saying: “Providence has given the United States the duty of extending Christian civilization. We come as ministering angels, not despots.†The imperialists won and in December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris sent the Spanish empire packing and the US made its debut as a colonial power (albeit a “benevolent†one, in the eyes of its leadership). The US annexed Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines (after paying $20 million). As American colonial designs became clearer under the banner of “Manifest Destiny†and buoyed by an economy on overdrive, its military became more and more adventurous in targeting enemies on foreign soil—something that Obama has vowed to continue, in Pakistan, for example, if its leadership does not do anything about Islamic extremists. A rescue party was sent by the Americans to relieve the Spanish stragglers inside Baler Church. A plaque to commemorate this event can be seen a few meters from the church. It reads: “Lieutenant-commander James C. Gilmore, U.S.N., commanding the U.S.S. gunboat Yorktown, was captured, together with all his command, save two, who were instantly killed and two mortally wounded, by insurgent forces, when he came to Baler in April 1899 to relieve the half-famished Spanish garrison that had been besieged in the town church for nearly a year. Lt. Gilmore and the survivors were taken to Nueva Ecija, and then to northern Luzon. They were later rescued by American forces and taken to Manila.†Thus the American experiment in “benevolent assimilation†or “making the world safe for democracy†began (its legacy can be seen in Iraq where more than 13,000 civilians have died). The imperialist American leadership of 1898, giddy from defeating the crumbling Spanish empire saw themselves as a kind of God-sent force, a beacon of hope for the “uncivilized†parts of the world. Ever since 1898, the new superpower has “pursued a strategy of remaking the world in its image, through free trade, military dominance, and globalization,†in the words of Boston University professor and historian Andrew J. Bacevich in his book “The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism.†How does this relate to present events? In a 2007 speech to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, Senator Obama proclaimed: â€I reject the notion that the American moment has passed. I dismiss the cynics who say that this new century cannot be another when, in the words of President Franklin Roosevelt, we lead the world in battling immediate evils and promoting the ultimate good. “I still believe that America is the last, best hope of Earth. We just have to show the world why this is so. This President [Bush] may occupy the White House, but for the last six years the position of leader of the free world has remained open. And it’s time to fill that role once more.†Is this what constitutes a repudiation of the past, a break from the misbegotten policies of the Cheney-Bush years? Isn’t this a recasting of the imperialist Senator Nelson’s words of 1898, shorn of Biblical imagery and updated for the 21st century sound bite?

“Providence has given the United States the duty of extending Christian civilization. We come as ministering angels, not despots.†

The Siege of Baler ended in June 2, 1899 when the survivors surrendered to the Filipino force, who, perhaps sensing that they were on the verge of a new era which required charitable acts, let the remaining soldiers return unharmed to Spain as heroes. Unfortunately, that era’s change agents, the “ministering angels†who landed in the Philippines full of good intentions, stayed for forty years of occupation in which an estimated half a million Filipinos were ultimately killed and injured in the guise of pacification. Justifying his decision to annex the Philippines, President McKinley crowed: “There was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them.†So, as the US election campaign reaches fever pitch and Obama’s “Vote for Change†is on the verge of closing the deal, I cringe a little bit as I look on the plaques in Baler town which serve as silent reminders on how such good intentions by the American empire can turn hope into grief for us in the receiving end of American foreign policy since 1898.