ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Topstories

News

College editors in the years of living dangerously

By PING GALANG

Among the most active in the opposition to Ferdinand Marcos’s design to stay in power beyond his term were the young editors of campus newspapers in colleges and universities across the country. As early as 1969, years before martial law was imposed in 1972, the college editors had already suspected the plan and worried about the harm it would do to democratic institutions and to the Filipino society in general.  The campus journalists, belonging to the League of Editors for a Democratic Society-College Editors Guild of the Philippines (LEADS-CEGP) at the time, also became activists, taking lead roles in demonstrations aimed at dissuading Marcos from pursuing dictatorial tendencies.

The campus journalists, belonging to the League of Editors for a Democratic Society-College Editors Guild of the Philippines (LEADS-CEGP) at the time, also became activists, taking lead roles in demonstrations aimed at dissuading Marcos from pursuing dictatorial tendencies.

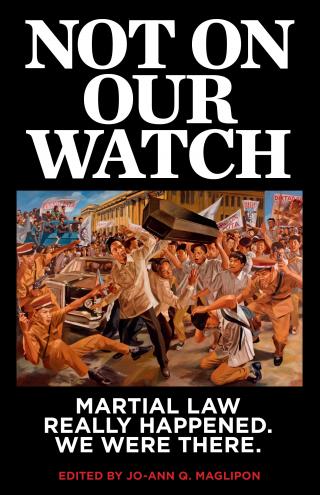

Many of them suffered for that, but imbued with purposeful idealism and courage—combined with a firm belief that the pen was mightier than the sword—kept them sustaining the flame of the student protest movement then just taking roots in the country. Many of them would later, when martial law did come, join clandestine resistance groups producing literature that exposed the deceptions of the so-called “benevolent dictatorship.” A number opted to take to the hills, some of them ending up martyred in the hands of the dictatorship’s forces. A few of them, widely admired in campuses for their sharp prose and intellect, got vanquished in the fighting fields without a trace, never heard from again. Two years ago, small gatherings among them led to a “10.10.10 Reunion” on October 10, 2010 that was attended by a sizeable number of the surviving campus editors. The reunion gave birth to “LEADS-CEGP 6972” that in 2011 was formally incorporated ahead of a second reunion. During those reunions, an idea for a book that would compile their stories emerged. The stories that were shared during the reunions were mostly about the sufferings they went through during the campaign against martial law as well as about families, careers, business ventures, exiles, and journalistic pursuits. Their stories now form a new book, “Not On Our Watch: Martial Law Really Happened; We Were There”, that will be launched this week (May 10) in a ceremony at the Metropolitan Museum on Roxas Bloulevard. The program starts at 5 p.m. Vicente Wenceslao and Elso Cabangon, of LEADS-CEGP 6972, introduce the book as an anthology of 14 stories that “illustrate how, when sacrifices were required of us, we did not let our country down and how, when our civil liberties and human rights were violently violated, we manned the barricades and defiantly shouted, Not on our watch!” Theirs are stories about “true-to-life harrowing events, as well as light—even funny—moments amidst the dangerous situations that some of the writers faced.” Authors featured in the compilation are: Jose “Butch” Dalisay Jr., Manuel Dayrit (former health secretary), Roberto “Obet” Verzola (UP Math instructor and pro-farmers advocate), Diwa Guinigundo (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas deputy governor), Jaime FlorCruz (CNN Beijing bureau chief), Calixto Chikiamco (economist and columnist), Al Mendoza and Soledad Juvida (Palanca Awards winners), Jack Teotico (Contemporary Arts Philippines publisher), Jay Valencia-Glorioso (Repertory Philippines stage actress, opera singer and recent Aliw Awardee) , Vic Manarang, Angie Tocong Castillo, and Vic Wenceslao (businessmen/entrepreneurs). Edd Aragon (artist/cartoonist) provided illustrations. One of the stories, “Lest We Forget” by Obet Verzola, tells of “memories [that] are painful to recall.” Verzola writes: “For years, I had nightmares about those events. These bad dreams usually involved getting the house I was staying in raided by the military, finding myself in prison again for some kind of political offense, or running from my military pursuers with my legs struggling in frustratingly slow motion. In my forties and fifties, the bad dreams came less often, though I still had them occasionally.” After experiencing the “first stirrings of an activist political consciousness” during a 1970 exposure trip to a Nueva Ecija village at the lower foothills of the Sierra Madre mountains, Verzola later became “a writer for the movement.” Obet Verzola writes about friends and colleagues in CEGP and other campus groups who were arrested or had “disappeared” during trips to the provinces. His own arrest—and torture at the hands of his captors—is a gripping narrative that will be long remembered for its harrowing details. But there are more revelations in Obet’s story that are bound to stir animated discussions about the martial law era and the myriad conflicts which have become tied to that regime, including the Plaza Miranda bombing. The death of a young recruit of a student organization—hit in the head by a “pillbox” bomb thrown from a window of a building along the route of a protest march—and the difficult soul-searching it caused on the group leader, is another memorable story in “Not On Our Watch”. Penned by Butch Dalisay, “The First of Our Dead” captures in spectacular fashion the impact of a casualty suffered by a secret organization and the chain of events that followed. There were others who were not as unfortunate, however. Al Mendoza, picked up by policemen in his sleep at his hometown (Mangatarem, Pangasinan), escaped a cruel reception in jail only after the local judge, an acquaintance of his parents, intervened and warned the cops against hurting the young student from Philippine College of Commerce. His crime: being “a communist” for leading his playmates in some “peryodikit” operations at the town plaza. The variety of the stories in the compilation makes it a very good read. Indeed the collection was the result of a simple question asked by the incredulous children of a CEGP member upon learning that she had been editor-in-chief of her college newspaper: “You, an editor?” Hearing her story during the reunion, the others felt that perhaps it was time to tell their children and the world their stories. Thus, the book was born. (This early a sequel is already being discussed.) Jo-Ann Maglipon, editor-in-chief of Yes magazine (she was herself an activist-journalist in those times), edited the book. The prologue was written by newspaper columnist Conrad de Quiros. Copies may be ordered at telephone (02) 919-0264, or by emailing Elso Cabangon at kasoels@yahoo.com. @yahoo.com>

More Videos

Most Popular