ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Topstories

News

Dispatches from post-Yolanda Tacloban

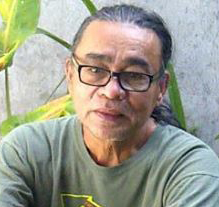

By RAYMUND L.FERNANDEZ

Dispatch 204, Tacloban

Raymund L. Fernandez

December 31, 2013

It was a rainy morning in Tacloban when he woke up to find they had brought no sugar-free coffee with their rations. And so he resolved to walk as far as he might to find a cup. Four people, loosely related, drove overland from Cebu to Tacloban to comfort themselves by looking up old friends and seeing how they were doing. Two of his women companions grew up here. He was only their driver. But he too had old friends. It was a difficult drive made dismal by the roadside vista of absolute destruction that they had never seen before, though none were strangers to typhoons.

They had spent the night comfortably in Rosvinil Pension at Burgos St., one of the few hotels that hadn't closed since Yolanda. It was here where a major TV network was headquartered and took most of its footages of the killer-typhoon. Even so, he woke up quite groggy. He didn't walk far to find the object of his search. Over the sidewalk at the street corner he found a small stall of two tables sheltered by tarps and a beach umbrella serving bread and drinks. Behind it, the remains of what might have been an old wooden house now almost completely demolished. Its absent owner, a foreigner, had allowed a few families to set up makeshift shelters here.

The rain picked up but he found his coffee, not sugar-free but regular three-in-1. He allowed this compromise. It was served by Lucia Lacaba and her companion, Danny Mojica. With his coffee came the privilege of sharing their story of survival.

They were a family of seven who operated a small store near the coastal area where the public market once stood. They had been evacuated to the Day Care Center nearby when Yolanda made landfall. Danny remembers counting the waves. The first one, not so big. The second one demolished the center and swept them all away. He took his grandson Mathew under his arm and clung to a barrel floating in the water. He thought they were going to die. But the water swept the both of them to a concrete building blocks away, just meters from where they now have their stall at Real St. and within sight of the now iconic unroofed belfry of the Tacloban Cathedral. He held on to a ledge and lifted himself and his grandson from the water. He stayed here until the water receded.

He had no way of finding out what happened to the rest of his family. While Yolanda blew its fury, he could hardly see in front of him. Debris was flying and floating everywhere. He thought they were all dead. He would later learn how all were carried by the waves through different inundated streets until they found some structure to climb up to. Unbelievably, all survived. It helped, perhaps, that they had grown up all their lives near water. They proved themselves good swimmers.

But Lucia lost four from her side of the family. Over the course of this interview he saw her slowly begin to cry as she listened from the far end of the stall. She must have felt at a loss reducing this mix of emotions into such a scale as the heart might reasonably contain. He could not do it for himself. And he was only a stranger here.

But Tacloban is growing back, just like the new growth of leaves on trees which had been stripped absolutely bare by the onslaught of wind and water just four weeks ago.

As he drank his coffee her heard Danny deliberate with Lucia if they should construct a small sitting bench for their stall. Wood was everywhere. But they were also waiting for government to appoint them their "bunkhouses."

A foreign volunteer dressed as Santa Claus distributes goodies on Christmas Day to young survivors of Typhoon Yolanda in Tacloban City on December 25. Survivors from the Philippines' deadliest typhoon spent a gloomy Christmas surrounded by mud as heavy rain drove many inside their flimsy shelters. (Photo: AFP/ Ted Aljibe)

As he drank his coffee her heard Danny deliberate with Lucia if they should construct a small sitting bench for their stall. Wood was everywhere. But they were also waiting for government to appoint them their "bunkhouses."

Just like before all this, they are at the mercy of government. It is a government they cannot fully trust. This was the same tradition of government that made this disaster something just waiting to happen.

In the time of martial law, it was tradition to cover the slum areas with temporary walls to hide the poverty from the former First Lady's foreign friends. Any development here was mostly more cosmetic than actual. Imagine a beautiful city set like a jewel amidst such a huge swathe of poverty living in flimsy hovels at the coastlines. How can anyone not help but ask: how did we allow them to live this way for so long?

Dispatch 205, The Mask

January 5, 2013

It took Yolanda to unmask not just Tacloban, but all of us. For we too have our own marginalized poor living in slums near the coastline, and we might as well rid ourselves of the notion that a typhoon does not select its victims. The poor are the first to die and suffer the most after everything falls apart.

It is not just the simple fact their flimsy houses are more vulnerable. There is also the fact they have little potential to store the most basic human needs, food, water, medicine, etc. Thus, "looting" became inevitable a few hours after the typhoon struck. Many business establishments chose to open their stores to the public. Rice, canned goods, even pharmaceuticals were available for free to those who walked through the wreckage in the streets in the short hours before darkness came. Most businesses hoped that, though they might lose their stock, their buildings would at least be safe.

Police and other officials of government were victims themselves. It is possible a number of them joined in the looting, but there should be a distinction made between those who looted for survival and those who looted for profit, "professional looters" who carted away appliances in trucks. It was clear the typhoon had brought about a breakdown of everything.

The survivors communicated with each other only by word of mouth. Other forms of communication became quickly inoperable. The local government structures completely fell apart. As was predicted by international media, Tacloban became "uninhabitable." And so the exodus of everyone who could, happened. Yet, only the rich and the middle-class had the option of escape. The poor had nowhere to go.

The poor of Tacloban are still there along with a few local heroes who, though they are well-off, chose to stay. If we ask whom we should listen to when we determine how Tacloban should recover, these are the people to ask. Not the government. The task of recovery starts by retelling their stories or allowing them to tell their story themselves. It is not a simple story. We would all learn a lot.

We must not forget that Tacloban after Yolanda is the story of all Filipinos. The same universal history of quarreling political dynasties, the same torn out fabric of governance, the same social stratification, the same topography of human misery, the same slums, the same poverty, exactly the same vulnerabilities just waiting to be unmasked by the next cataclysm.

And in the middle of all these, a small layer of well-educated people, civil society, who see all sides of their city. They are middle class professionals, people who own businesses but are not as well-entrenched in politics as the local politicians.

The politicians have a long history of failure here. They continue to play the game of Manila-centered politics. They plot their political trajectories along lines of a particular reasoning: is the choice of Panfilo Lacson for rehabilitation czar the result of a decision made to appease the Chinese communities? Is he making a play for the presidency? Will he succeed in rehabilitating Tacloban?

PNoy administers the oath of office to Presidential Assistant for Rehabilitation and Recovery Panfilo Lacson at Malacañang on December 10.

But how should we define success? Even now, Tacloban is slowly being cleared of garbage which, earlier, covered everything. The typhoon buried the downtown area under many feet of muck which looked, and smelled, like greasy sewage, the very same sewage the city had been dumping into the sea from time immemorial has now returned to it within a few short hours of the storm. This muck is gone. The streets have become passable again, but just barely so. There is still debris and refuse by the roadside. There is a smell in them which suggests they might still contain buried dead, but this will all be cleared eventually. The people are moving.

There is a resolve not to allow the poor to build in the coastal areas. It is now close to four weeks since Yolanda made landfall here. There are makeshift shelters everywhere. They are the poor's alternative to the tent cities which have also grown where slum houses used to be. But if former residents are not allowed to rebuild their houses here, where will they go? So far, there is no talk of resettlement areas. The work of rehabilitation has not yet gone that far.

Who finally decides these things? What precisely is the process of decision making? It will be a sad thing if this will be left entirely up to Tacloban's traditional politicians. They would all be content to return Tacloban to a semblance of what it was. That after all was the Tacloban who elected them.

A better goal would be to make Tacloban a better city than it ever was, to make it a city where the most essential things are in their right places and there will be less of the old inequalities which exacerbated this tragedy, a model, perhaps, for other Philippine cities.

In the story of Tacloban's recovery we could find the true logic of how a city can improve itself. And this might give us all exactly the thing Tacloban needs for herself: hope. — KDM, GMA News

Raymund L. Fernandez is a columnist for the Cebu Daily News where "Tacloban" and "The Mask" were originally printed. We are re-posting it here with permission.

More Videos

Most Popular