ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Topstories

News

Safe water is a human right, but costly in waterless town in Northern Samar

By JAKE SORIANO, GMA News Research

Last of two parts

Close to half of the entire population of Northern Samar is poor.

Data from the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) reveal that four in every ten households in the province live below the poverty threshold.

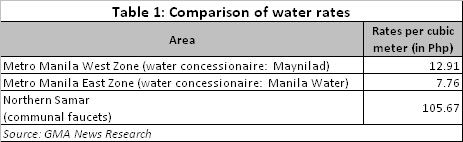

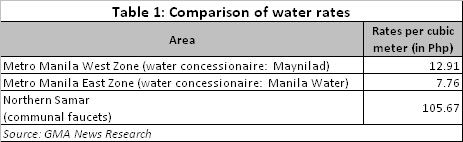

Yet the people of Northern Samar pay more for their supply of water, an essential human right explicitly recognized by the United Nations, than residents of Metro Manila where the Philippine capital is located.

They pay ten times more.

In the municipality of Catubig, whose name ironically sounds very much like the Filipino word for water, residents line their water containers up at tap stands located in designated areas.

The most common container used in fetching water is a black plastic galon which could carry roughly five gallons of water. Each galon of water costs two pesos.

Even Catubig Mayor Fredicanda Dy complains this is too expensive.

“Kahit sa akin, gumagastos ako more than Php 3,000 a month. Eh kung ordinaryo ka lang, marami kang anak, so malaki yan sa pamilya. Samantala kung may water system, malaki na ang babayaran na Php 500 sa isang pamilya. Malaking savings yun [I myself spend more than Php 3,000 a month for water. If you’re an ordinary citizen and have a big family, that amount is simply too much. If there’s a reliable water system here, we’d be spending less than Php 500 a month for water. The difference translates to huge savings for everyone],” she says.

For about three hours every morning and every afternoon, water flows from communal faucets.

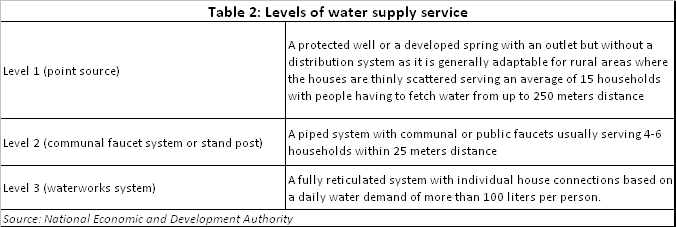

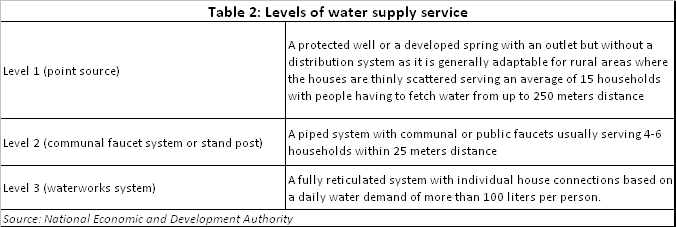

“Ang water system namin is level two. Meron kaming water system streets [We have communal faucets in the streets,]” says Dr Sylvia Pacle, health officer of Catubig.

"Ang water source namin is from the spring to reservoir, from reservoir to streets. Wala pa sya sa kitchen. Dito walang gripo pa sa mga kusina [Water from a spring source is collected in a reservoir. From the reservoir, water goes to the communal faucets. No individual water connections in households]," she explains.

Purified drinking water is available but only for residents who can afford Php 30 or more for every container. This is already a luxury. Boiling water from the public faucets is enough for most.

Those who cannot afford even the water from the faucets turn to other risky sources like rivers, brooks and springs.

“Hahalo kami sa kalabaw at baboy [We bathe with water buffalos and swine,]” says Emelita Ronato of Barangay Hiparayan, describing bathing in a body of water in her village. She pauses and then adds, “at sa basura [with garbage as well.]” She laughs at the memory.

Five barangays in the Catubig poblacion (town center) are considered waterless by the National Anti-Poverty Commission. They are only five among the 1,353 waterless villages in the country.

NAPC, the government agency in charge of programs to address basic inequities in the Philippines, determines that a barangay is waterless when more than half of its total population does not have access to safe water.

“Yun ang number one na kailangan namin. Tubig [That’s the main thing we need. Water],” says Mayor Dy.

“Pumunta ako kaagad sa LWUA. So nag-create kami ng Catubig water district. Nag-apply kami ng loan. Pero malas lang. Hindi na natuloy yung loan namin [First thing I did to address the water problem was apply for a loan from LWUA. We’d already built a water district but the loan unfortunately was not granted],” she narrates.

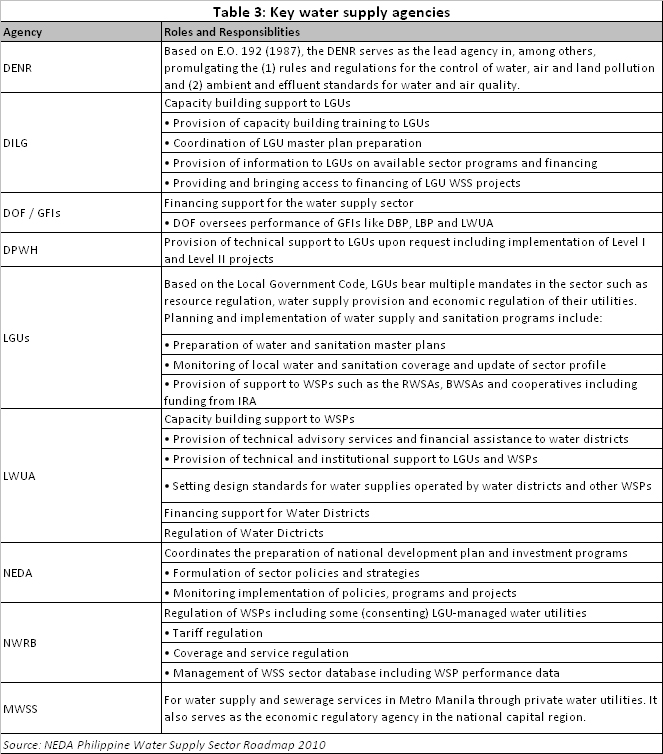

LWUA, or the Local Water Utilities Administration, is in charge of financing and regulating water districts outside Metro Manila. It has under its jurisdiction 859 water districts as of December 2010.

“Lumapit din ako sa DOH (Department of Health), through NAPC, sumulat ako, nagsubmit ako ng program of work pero hanggang ngayon wala pa [I also asked DOH through NAPC for help. I’d already submitted my program of work but I got no response until now],” she continues. “Si Governor Paul Daza may mga company na nag-offer sa kanya na tutulong. Pero hanggang ngayon wala pa naman. Pero... naghihintay pa rin ako sa magandang resulta [Private companies also offered help to Governor Paul Daza. I’m still waiting and I hope it goes well].”

A fragmented government model

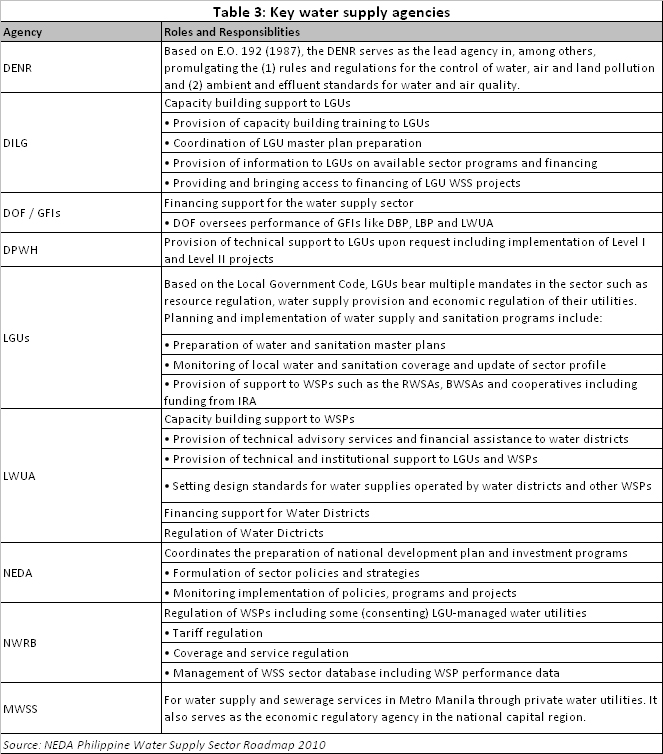

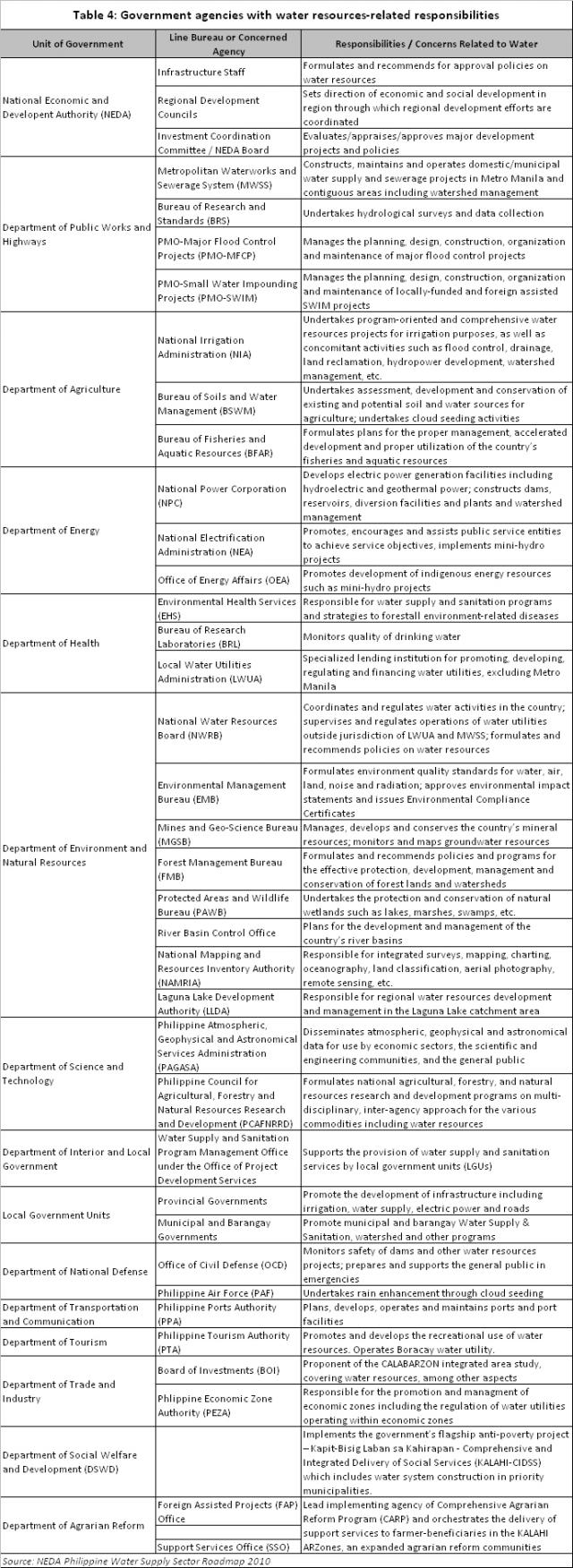

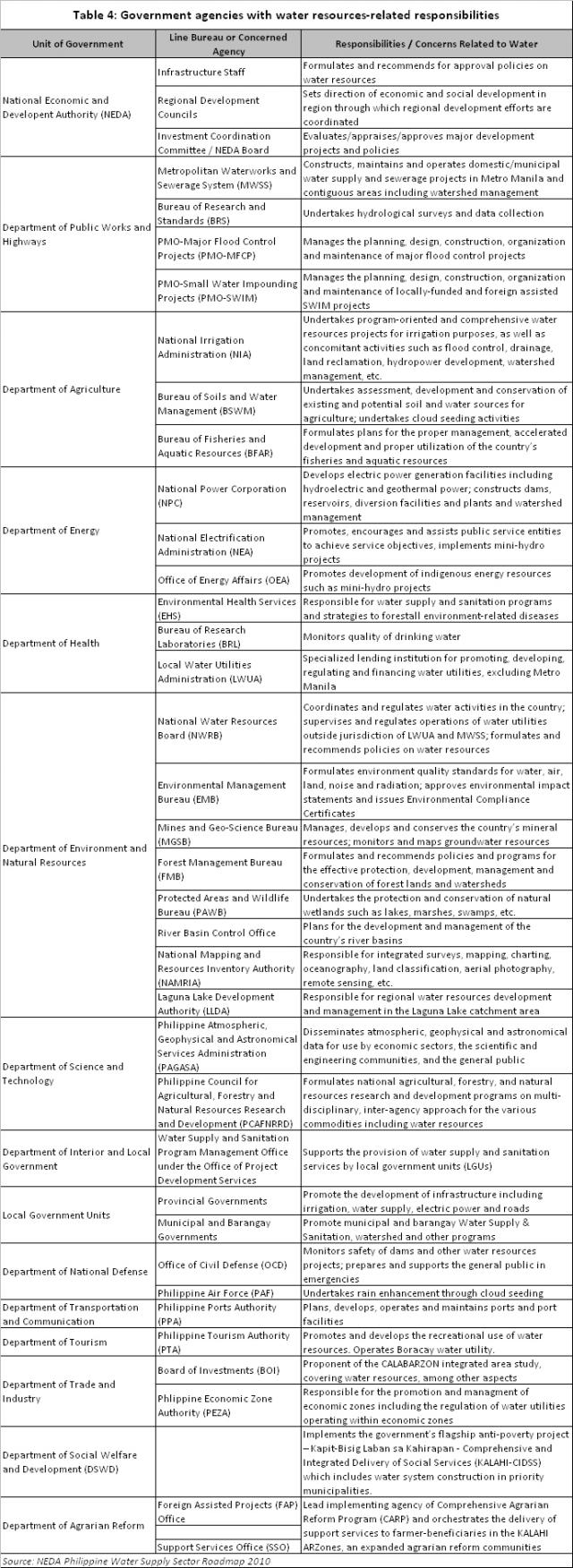

The agencies mentioned by Mayor Dy are just three of the many government arms, too many in fact, in charge of the water situation in the entire country.

In its water supply roadmap report in 2010, the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) has identified more than 30 agencies, with the observation that the “existing structures have different regulatory practices, processes and fees with cases of overlapping functions or jurisdictions. This environment suggests a fragmented regulatory framework and lack of coordination."

NEDA formulates and recommends, as well as evaluates and approves, government projects and policies on water resources.

The National Water Resources Board (NWRB), regulates water utilities not under LWUA. As of December 2011, it has granted permits to operate to 433 utilities outside Metro Manila.

While the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS) serves the Metro, there still are 136 water utilities under NWRB within the region.

Other water service providers in the country include cooperatives and community-based organizations.

NEDA estimates there are about 5,400 providers, most of them “reportedly not performing well in service delivery.”

Bittersweet

Barangay Hiparayan enjoys adequate and clean water and is nowhere in the NAPC list of waterless barangays, no thanks to the government.

PLAN Philippines, a non-government organization which funds projects to help poor children in communities nationwide, donated the village’s water system.

PLAN Philippines Northern Samar coordinating manager Boots Rebueno explains that a supply of clean water is extremely important in his organization’s advocacies for children.

“Yung mga bata kasi, ang vision ng PLAN is for them to realize their full potential [The vision of PLAN Philippines is for children to realize their full potential,]” he says. “Papano mo matutupad yun kung two years old patay ka na dahil na-diarrhea ka dahil wala kang access sa tubig na malinis. Wala na. Yung full potential mo hanggang two years old lang [How would they realize their full potential if they perish at two years old because of diarrhea and other waterborne diseases. That potential is gone].”

Ancient water pipes that pass through the rice fields used to provide water to the village. The water that came out was suspect at best.

“May lumalangoy na itim [Black organisms are swimming in the water],” Emelita remembers her experience fetching water one time. “May linta sa tubig [Our water had leeches]!”

The days of slimy surprises in their water are over.

Yet today's clean water conjures bittersweet emotions to Annabelle Perez.

“Nung wala pang tubig, mahirap ang buhay namin. Ang iniigiban namin, malayo. Doon pa sa bundok [Those were days when life here was hard. We have to walk miles just to fetch water. Up there in the mountains],” she says.

She then tells the story of the son she lost.

“Yung anak ko nagka-ano yan, nagtae ba, tapos nagsuka [My son had diarrhea and started throwing up],” she says. “Siguro, nakainom ng tubig na hindi malinis. Kasi wala pa man tubig na malinis [It may have been the unclean water. Back then we didn’t have clean water].” Her voice starts shaking. “Tapos hindi ko nadala sa hospital namatay agad sya. Mga ilang oras lang [I wasn’t able to bring him to the hospital. He died only after a few hours].” She breaks down.

“Mamamatay ang tao pag walang tubig [People die without water],” she says.

Immediate versus long-term

Boots Rebueno of PLAN Philippines notes that water system infrastructure is not everything.

“Yung paggawa ng water system, hindi sya as easy as magconstruct ng structure [Building a water system is not as easy as building the structure],” he explains. “Merong capacity building. Critical yun [Capacity building is important],” he says.

PLAN invested on leadership and other training programs so Hiparayan residents could keep the water system working even after the organization leaves the village.

“Two years, three years from now, we will go to another province na poor. Doon na naman kami magsisimula ng development activities [Two or three years from now, we will leave this village to start development activities in another poor village],” Rebueno says, adding that he believes the trainings PLAN Philippines has provided will help sustain the water system.

Dr. Melodia Nerida, chief of the Catubig hospital, summarizes one essential problem in the water sector, based on her personal experience in Northern Samar: It ultimately boils down to the immediate needs of a community versus its long-term needs.

“Hindi pa matugunan yung problema namin sa water, meron na naman kaming immediate na problema [before we could even fix our water system, other more immediate problems come up],” she says.

Working in a hospital with leaky roofs and defective electrical wires, she says facilities for water are pushed down in the priority list.

Leaky roofs could cause flooding in the hospital, she explains. Faulty electrical wires could blow up any moment and cause fires.

“Government should solve all problems,” says Northern Samar Governor Paul Daza, but again “depending on its financial capabilities,” he adds.

Governor Daza is in his first term as governor of the province after serving a term as representative of Northern Samar’s first district. He replaces his father, now Representative Raul Daza, who was the province’s governor from 2001 to 2010. The older Daza currently holds his son’s former post in the House of Representatives.

The younger Daza believes that government partnerships with the private sector are key to the water problem in his province.

“Ako, palagay ko yung magandang model, government pondohan yung infrastructure. Private to operate and maintain [I think the best model is for the government to fund the infrastructure and for the private sector to take charge of operations and maintenance],” he says.

The reality is much more complex with the present fragmented nature of the government bodies in charge of water.

The NEDA water roadmap provides a striking example: In 2009, the national government subsidized waterless barangays by giving LWUA some Php 1.5 billion in funds to support the revival and creation of new water districts.

“Although it may be argued that these invest¬ments contributed to service expansion, still the public resources were not used for the top priority areas,” the roadmap reads. “If these new districts do not achieve technical and financial viability, then the investments would have been put to waste.”

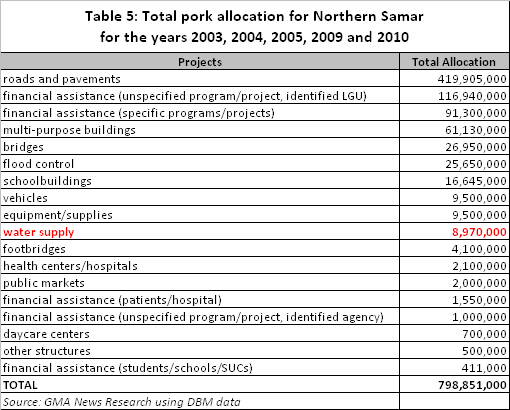

Funding water infrastructure projects also is highly subject to the discretion of government leaders.

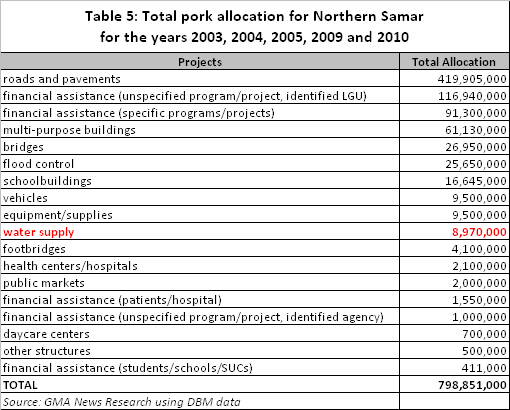

A GMA News Research study finds that pork barrel funds (both the Priority Development Assistance Fund and the Department of Public Works and Highways fund of legislators) allocated to Northern Samar in five years amount to less than nine million — just 1 percent of the total pork allocation for the province in those five years.

Policy changes

To address the fragmentation, President Benigno Aquino III issued in October last year Executive Order 62 which, among others, creates an inter-agency committee on the water sector with the DPWH secretary as head.

The committee is tasked to “design and recommend to the president a water sector master plan which will effectively address all the issues and concerns of the water sector.”

A bill in the Senate introduced by Senator Edgardo Angara notes that this is laudable but “it may only result in adding another layer into the bureaucracy to complicate an already confused system.”

In the House of Representatives, at least 26 bills connected to water have been filed in the 15th Congress. They concern amendments to the Clean Water Act and other laws, local bills designating watershed areas, and bills rationalizing financial and economic regulation of water utilities.

“Maganda yan. Maganda yang pakinggan [That’s good in theory,]” Boots Rebueno of PLAN says. “Pero ang laging challenge dyan kung paano magti-trickle down doon sa pinaka-ibaba. Hanggang sa barangay [But the real challenge is how these policies and laws trickle down and affect the lives of the people down to the level of the villages].” — RSJ, GMA News

Tags: worldwaterday, northernsamar

More Videos

Most Popular