ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Topstories

News

In “waterless” Tawi-Tawi, water is nobody’s priority

BY JAKE SORIANO, GMA NEWS RESEARCH WITH THE GMA NEWS SPECIAL ASSIGNMENTS TEAM

(First of two parts) Living in the southernmost province of the Philippines, Radgma Papa has mastered the art of telling when rainwater is dirty and when it is safe for drinking. Looking at the overcast sky, she says, “Madumi pa yan. May dust pa. Kita naman sa tubig kung malinis na. [Water from the first few minutes of rain is still dirty. It still has dust. You can tell if it is safe for drinking when the water turns clear.]”

A few minutes later, heavy rain starts to pour in Barangay Lakit Lakit in Bongao, the capital of the province of Tawi-Tawi. May is a summer month. But while it does get hot in Bongao during certain times of day, that particular week in May, it kept raining.

Radgma waits. After some 10 minutes has passed, she sets up her blue water container beneath a gutter where rainwater flows from the roof of her house. She, like most residents of Tawi-Tawi, relies on collected rainwater for drinking.

The province, closer to Sabah in Malaysia than to the Philippine capital of Manila, is composed of 11 island municipalities: all are tagged waterless by the National Anti-Poverty Commission (NAPC).

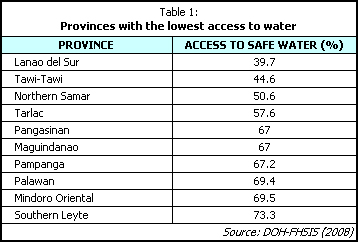

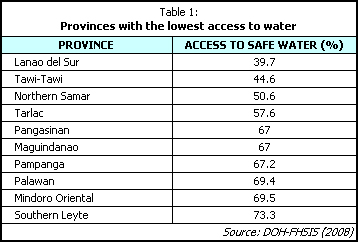

In fact, Tawi-tawi is among the provinces with the lowest access to safe water.

— ELR, GMA News

In 2010, the United Nations declared safe and clean drinking water a human right "essential to the full enjoyment of life and all other human rights."

The Philippines, in the age of wifi connection, does not even target 100 percent access to safe water – the commitment is merely to halve the number of those without access by 2015, aiming for an access rate of 86.5%.

Tawi-Tawi Representative Nur Jaafar admits that water is the most urgent need of the province. “Para sa akin eh yun ang number one, [For me, access to water is the number one problem,]” he says.

Water supply projects are identified as among the priority infrastructure in the pork menu – a list of projects that could be implemented and funded by legislators’ pork funds.

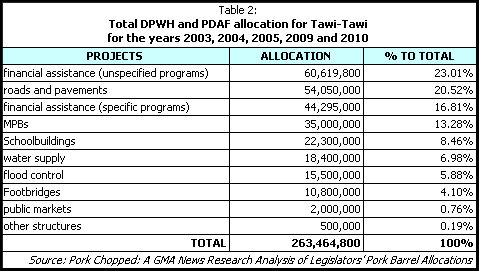

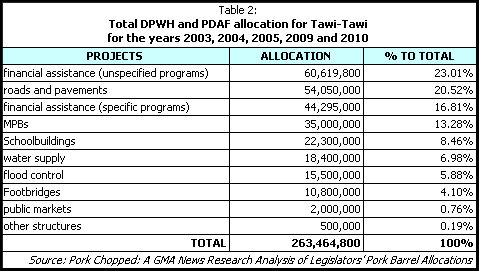

Yet in Tawi-Tawi, legislators allocated only Php 18.4 million -- a mere 7 percent-- for water supply projects in five years.

The said amount funded 13 projects: seven concrete water tanks, three elevated steel tanks, a PDAF allocation for the installation of water tanks and two other unspecified water supply projects.

The top allocation for the province went to financial assistance to projects that were not specified in the budget department’s pork data.

These were among the findings of a study on five years of pork allocations: “PORK CHOPPED: A GMA News Research Analysis of Legislators’ Pork Barrel Allocations.”

Nationwide, water supply projects were allocated Php 3.2 billion in pork funds for the years 2003, 2004, 2005, 2009 and 2010.

The amount chipped off 4 percent from the Php 83.27 billion pork allocations made in those five years.

Compared with the other provinces with little access to safe water, Tawi-Tawi’s 7 percent of water projects from pork already may seem a downpour.

Northern Samar, the province with the third worst access to safe water rate in 2008, received only 1 percent of pork funds for water supply in the same five years.

Lanao del Sur, least access

Lanao del Sur, tagged as having the least access to safe water in 2008, got an allocation of P25 million for water supply projects in the five years covered by the study.

That’s a mere 4 percent of the total pork the province received in those years.

Like Tawi-Tawi, Lanao del Sur’s top pork item is financial assistance for programs that were unspecified in the available data.

GMA News Research tried to get an interview with Representative Pangalian Balindong, one of the two district representatives of Lanao. Rep Balindong was serving his term in the 2nd district in the two years of the study sample.

Instead of an interview, Balindong sent a four-page letter to explain the allocation of pork funds in his province.

“There are too many projects, and too few resources for conducting these projects,” Balindong says, “while prioritization is a political process (we continuously consult our people through local leaders and officials), I have always abided by a simple rule: to choose those projects that – given the constraint on the budget – create the greatest possible benefits for the most number of poor people.”

He says his office has “centered [its] priorities on school buildings, flood control, rehabilitating critically-situated roads, providing barangay-based peace patrol and anti-crime vehicles and equipment, small farm reservoir irrigation projects and potable water development, and rural electrification.”

Balindong notes that he has allocated Php 1.5 Million for water supply projects in 2010.

In his letter, Balindong says, “GMA- 7’s research about access to water in my district is a little erroneous.

“In the 2nd District of Lanao del Sur, the problem is not access to clean water per se, but rather low household access to piped-in water supply (or in water system development terms, Level III systems),” he says, noting that Lake Lanao is an ample source for ground water and potable water.

The data on the access rates to safe water used in the study are not generated by GMA News Research.

The access rates are based on the official figures from the Department of Health’s Field Health Service Information System which reports precisely the proportion of households with access to safe water supply to the total number of households in a province.

This same data is used as among the references of the monitoring team of the country’s Millennium Development Goals.

GMA News Research sent interview requests as well to the office of Lanao del Sur 1st District Representative Mohammed Hussein Pangandaman but has not received an answer as of press time.

Least sustainable, least safe

Like Radgma Papa, Imelda Ibrahim also collects rainwater for drinking. She lives in Mandulan, a neighboring barangay of Lakit Lakit, also in Bongao. The rain has always been her source of drinking water. This has been the case since she was a child. “Meron na ako apo ngayon, [I have a grandchild now,]” she says.

A pork-funded tank stands beside Imelda’s house. It stores water from a dug well. Imelda says the water tank has helped ease her water supply problems.

But, she says, water from this source is useful only for washing clothes and bathing: the water is salty because the source is near the sea, and therefore is not fit for drinking or even for cooking.

Reviewing the pork allocations, GMA News Research finds that the pork-funded Tawi-Tawi water projects are classified as Level 1 projects: these are communal sources without a distribution system and include protected wells and developed springs from which people fetch water.

More Videos

Most Popular