Most of what Siotico “Tikoy” Agayan has called home for years was swept away by furious floods in February. His house now stands like a mouth wide open, caught by surprise by the waters that carried it away. Only one side of the nipa wall is left, the roof is partly gone, the bamboo slats that served as flooring are scattered like dominoes. Mang Tikoy scans the muddy swirls that had settled under the remains of his home. “Mag-ingat po kayo[Be careful,l] ma’am,” he says. “Baka may pako pa dyan[You might get hurt.]” His eyes rest on a pile of muddy clothes. They’re no good, the old man says, shaking his head. He and his wife had tried washing them but the mud has matted and refuses to come off.

Almost P200 million in pork barrel funds were spent for this sports complex at the Jose Rizal Memorial State University in Dapitan City, Zamboanga del Norte. GMA Special Assignments Team

“Ang mga damit namo.. mga plato, mga pinggan, naubos gyud. Ang mga kawali, na..ra ma’am ang mga kawali kay…[Our clothes.. plates, nothing was left. The frying pan…]” his voice trails off as he recalls what they lost in the flood. Mang Tikoy of Barangay Burgos is among the 13 thousand residents from the different barangays in Dapitan City, Zamboanga del Norte who suffered from the floods in February this year. The disaster council’s final report says the continuous rain submerged parts of Dapitan City in the worst floods the residents could remember. Dapitan City is composed of 50 barangays; one in three is identified as wholly or partly at high risk to flooding based on geohazard mapping. In public works, as a rule, roads and bridges are the priority, says Romeo Momo, Public Works undersecretary in charge of supervision and control of all regional operations. But for Zamboanga del Norte, Usec. Momo says, the priority is, “roads and flood control.” Any infrastructure funds in Zamboanga del Norte should first go to these two crucial projects, says the public works expert. A GMA News Research study of five years of pork barrel allocations finds that almost P200 million of pork infrastructure funds in Dapitan City were allotted not for roads, not for flood control but for the construction of a sports complex. “I am not surprised na bumabaha pa rin doon [I am not surprised that the place still gets flooded,]” Momo says when asked about the flooding in Dapitan City early this year. Of course, he says, the Department of Public Works and Highways has earmarked funds for flood control, but not nearly enough, always not enough. “Most of our releases to Zamboanga del Norte, may na-allocate for flood control,” the undersecretary says, “but a large portion is for the improvement of roads – upgrading of national highways kasi may mga gravel portions pa dyan….” Any available infrastructure funds for the province, including and especially pork barrel funds, he says, will be wisely spent on flood control. More than 10 percent of the DPWH budget is earmarked for the pet infrastructure projects of legislators for what is commonly known as the pork barrel funds. “Sana yung pera nila (pork funds), dun sana nai-complement sa flood control [It would be better if their (pork funds) will complement flood control,]” Momo says.

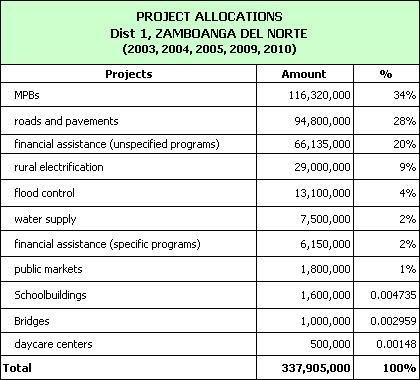

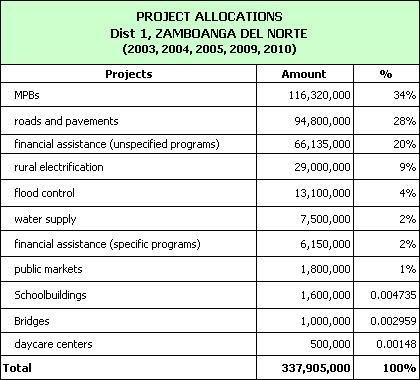

Top pork projects In Zamboanga del Norte, there is no shortage of needs where money could be spent on. It was the poorest province in 2003 and 2009 based on data from the National Statistical Coordination Board. Thus, every centavo counts, including the pork barrel earmarked for the province and its districts. The pork database of GMA News Research culled from the DBM website shows P83.2 billion were allocated nationwide for legislators projects in five years (2003-2005, 2009-2010.) Roads and pavements topped pork infrastructure projects in the country with P22.77 billion allocations. This makes up 27 percent of the pork-funded projects. Multi-purpose buildings (MPBs) rank second with P14.24 billion in allocations, nearly a fifth of the P83-billion pork pie. Flood control comes a far third with P5.2 billion. But in the First District of Zamboang del Norte, where Dapitan City belongs, the top pork project within the time frame of the study was not roads nor flood control; it was MPBs. In fact, the biggest allocation for an MPB project nationwide in the five years of pork allocations studied was in Dapitan City -- at least P92 million for an MPB in the Jose Rizal Memorial State University. In total, Zamboanga del Norte’s First District got an allocation worth at least P337.9 Million from the pork barrel in five years. More than a third of these funds went to MPBs amounting to P116.3 million. Roads and pavement followed with an earmark of 28 percent amounting to P94.8 milllion. Allocations for flood control were only at 4 percent, worth P13.1 million.

Nationwide, roads are the legislators favored projects. This is just fine with the DPWH. Building roads and bridges is after all the mandate of the public works department. MPBs, however, are not in the immediate priorities of the DPWH. “It’s not even complementary to roads, to national highways,” Usec Momo says. “But again, just the same, it’s public infra and because we are mandated to construct, as the implementing office, we have to do it.” DPWH is not consulted in the identification of pork infrastructure projects. Legislators simply identify their pet projects which more often are not in the list of priorities of the local public works; these are usually the MPBs. But Usec. Momo concedes MPBs may be important to the communities, too. “Kelangan din sila sa mga barangays as barangay hall, health centers, daycares,” he says. It would help, he adds, if the use of the MPB would be stated clearly from the beginning, whether for education, health or something else. “Para at least you’ll know where our money goes,” he says.

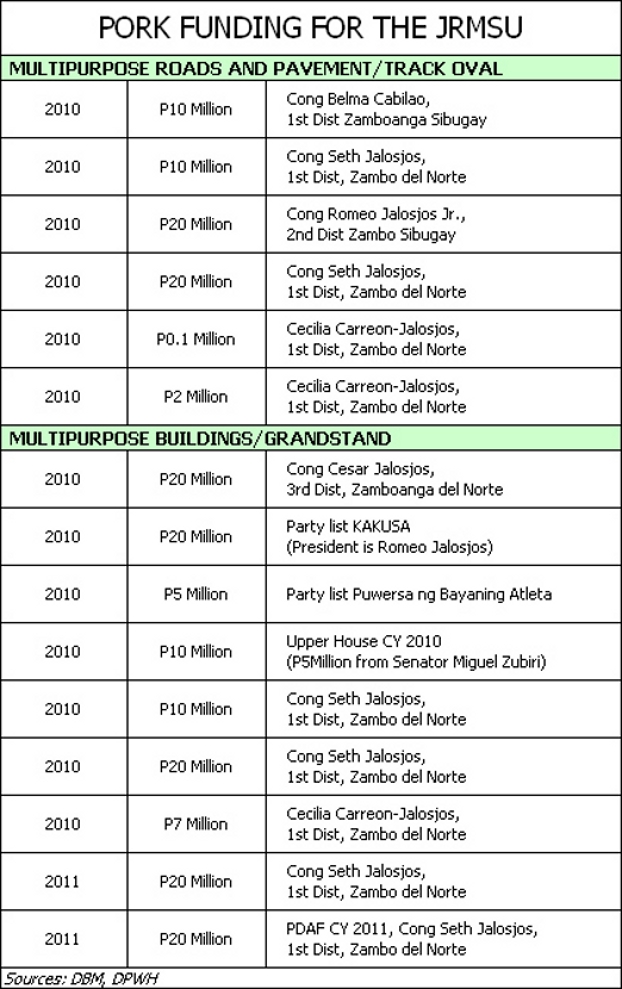

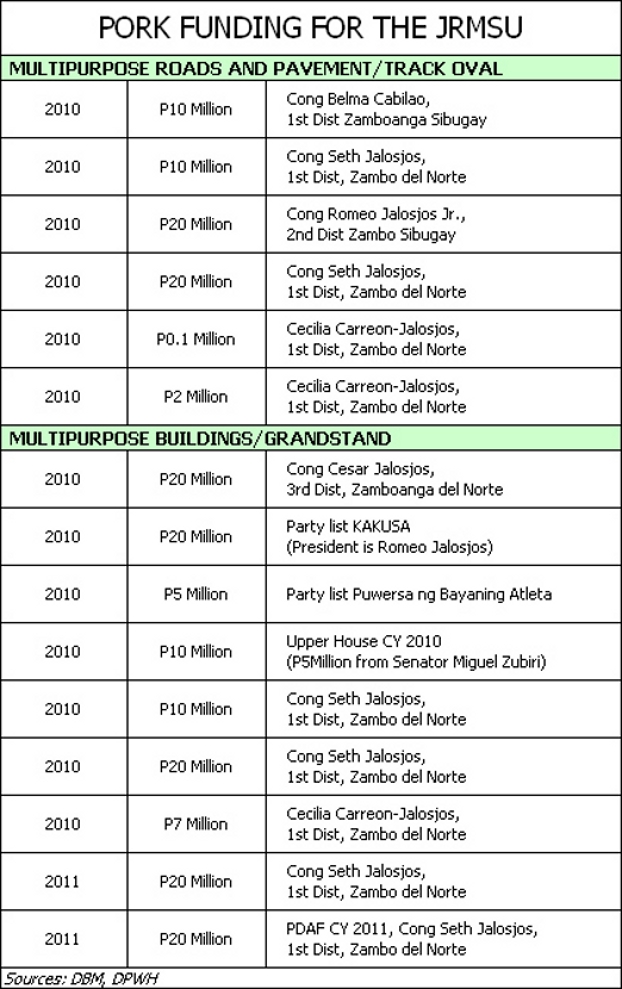

Pork for the sports complex At the JRMSU in Dapitan City, Rep. Seth Jalosjos has the goodwill of both students and faculty. DPWH and DBM records show that Rep. Jalosjos gave the most pork funds to the JRMSU sports complex among all the legislators who contributed, at least P100 million. The rest of the P194-million pork allocation for the project was made by other representatives and a senator. The amount does not yet include funds donated by the different local government units and other government agencies. In the pork database culled from DBM and DPWH records, at least P132 million was earmarked for an “MPB” inside the state university. The “MPBs” constructed were, in fact, grandstands for the sports complex. The P62.1-million pork allocation for “multi-purpose pavement” turns out to be for the track oval of the sports complex. Rep. Cesar Jalosjos of the third district of Zamboanga del Norte, uncle of Seth, gave at least P20 million of his pork to the sports complex. Rep. Cecilia Jalosjos, Cesar’s sister and Seth’s aunt, contributed almost P10 million from her pork barrel. Seth succeeded Cecilia as first district representative in 2010. “This is now the pride of Zamboanga del Norte. To have a national level of arena for competition, hosting Palarong Pambansa or athletics nationwide,” Rep. Cesar Jalosjos says in an interview with GMA News.

Rep. Cesar Jalosjos notes that many officials came together to fund the sports complex: senators, local officials even from neighboring provinces, and the Department of Education. Dapitan City Mayor Patri Chan says the sports complex was the initiative of former mayor Dominador “Jun” Jalosjos Jr., brother of Cesar and Cecilia and the uncle of Seth. “It was a success. Even Secretary [Armin] Luistro cannot believe that we finished that [the sports complex.] Kasi we started from nothing, we started from scratch,” Cesar says. “If not for the concerted effort from all these leaders, hindi namin magagawa yun [we couldn’t have done it,] we cannot host the Palarong Pambansa.” The JRMSU sports complex hosted the 2011 Palarong Pambansa.

Unimaginable sum To JRMSU officials, the almost P200 million of pork barrel funds allotted for their sports complex is an unimaginable sum. They say the total cost to complete the project may even reach P500 million. Based on the agreement signed between the school and the city, the sports facilities include a grandstand, an all-weather track oval, a warm-up track, an Olympic-sized swimming pool, a warm-up pool, a covered badminton court and a tennis court. Dr. Cecilia Saguin, vice president for academic affairs, smiles. “We welcome it. It will never come to our hands at any time in our lives…We are very thankful.” The school could never have afforded such project with its own funds, she says. The sentiment may not be an exaggeration: In the 2013 national budget, JRMSU gets P183 million—far, far less than the total cost of the sports complex. JRMSU had to let go of several buildings, including its College of Education and the College of Arts and Sciences to make way for the new sports facility. The school had agreed with the former mayor that the demolished buildings will be rebuilt and relocated in another part of the campus. Asked if the sports facility was what the state university would have spent for if they had the same amount of money at their disposal, Dr. Saguin says, “It’s nice to have…” If the university will ever have extra funds, she says, “May iba kaming kailangan [We have other needs as well.] Before nagput-up ng sports complex yung swimming namin sa marine, doon sa dagat [we go to the sea.] So we have alternatives. Kung magbabasketball, punta kami sa labas [For basketball, we play outside.] We utilize other areas.” The priority projects would have been more buildings for classrooms and equipment. “We are forced to offer evening classes because of the growing population,” Dr. Saguin says. Equipment comes next. “Ang technology mahal [Technology is expensive,]” she says. “Gusto naming ma-provide yun sa students [We would have liked to provide that to the students.]” More than a year after the Palarong Pambansa, the JRMSU sports complex stands unfinished and in disrepair. The multimillion track oval looks like an old, red carpet rolled out unevenly. The rubber has warped and cracked in many places. Rainwater has seeped underneath and puddles have formed over the cracks. In many parts, the rubber is torn, like big, red pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Only the main grandstand has taken form and shape. Most of the bleachers around the oval have yet to be completed. The steel frames are exposed and pieces of lumber are stacked soaking up the sun and rain. GMA News Research asks Usec. Momo to comment on the infrastructure projects funded by the pork barrel. Weighing his words carefully, he says, “Sana kung hard infra (ang project), it should be geared towards projects na talagang kakailanganin ng isang lugar [that the place really needs.]” Over the years of implementing pork-funded infra projects, were there times when he thought the money could have been spent elsewhere? He is quick to reply: “In many instances, yes.” In flood-prone Dapitan City, it was clear to Usec. Momo that the money could have been better spent. “It should not have been a priority,” he says of the multimillion sports complex. GMA News notes as well that the province of Zamboanga del Norte does not exactly lack for sports or convention venues. In fact, it has at least four, including the still-unfinished JRMSU sports complex. In the capital city, the sprawling multimillion-peso Dipolog Sports Arena is still under construction. There is also the newly constructed Zanorte Convention and Sports Center, which is almost adjacent to the Zanorte Convention and Exhibition Center. When asked if the construction of the multimillion peso JRMSU sports complex is aligned with the plans and priorities of the local government, local officials are quick to say yes. “Kasama sya sa tourism program,” Gov. Rolando Yebes says. Dapitan City Mayor Chan says the same thing: “We want to develop the city as sports tourism [destination.]” Says Rep. Cesar Jalosjos, “Mababalik rin ng tourism eh [The gains will be in tourism.] Babalik rin, so may mga sports activities kami dyan, may pupunta, so kikita rin yung mga yung mga bahay, hotels [When tourists come, the houses for rent and hotels will earn.]” Rep. Seth Jalosjos has declined all repeated requests of GMA News for an interview.

Living with the floods Tourism, however, may be the farthest thing in Mang Tikoy’s mind as he squats before the debris that was his house. Buried in the muck left by the flood are bottles of all shapes and sizes and colors, one red baby shoe, mismatched children’s slippers. When the waters came, five kids were in the house, including a baby. “Hindi kaya, ma’am, kay nagka-kwan mi, nag-ana man ang mga, kay nagtulong-tulungan man ang ..baha dito… [The flood current was too strong, we could not stay…] ” Mang Tikoy gestures with his hands, words failing to describe the force of the waters that took his house away. Looking at the damage, one could not help but think the worst: Did anybody get hurt? A slow smile breaks into Mang Tikoy’s somber face, “Wala naman po, salamat sa Dyos [Nobody got hurt, thank God,]” he says. Based on the findings of the Mines and Geosciences Bureau, Barangay Burgos is prone to localized flooding. This comes as no surprise to its residents; they have learned to live with the floods. Barangay Secretary Amelita Dagpin says, “Nasanay na kami sa baha [We’re used to the floods.]” Burgos gets flooded three or four times a year, with waters reaching knee-deep or waist deep. In 2006, MGB had recommended that infrastructures in Burgos be elevated to more than a meter. But that would not have helped them with the February floods. Barangay Captain Augusto Galanido stands on a bench and reaches as far up as he can to point to the top of one of the columns of the barangay hall. That was how high the water reached in February. “Lampas tao [Over our heads,]” the Kapitan says. The Dapitan-Oroquieta national highway in the area of Barangays Burgos and Sulangon becomes impassable when the water rises, isolating the two barangays. During the February floods, provincial buses were lined up, stranded on the highway, waiting for the water to go down. Residents say it took more than 12 hours for the water to subside. “Tubig ang problema namin. Kapag tag-ulan, baha. Kapag tag-tuyo, inumin [Water is our problem. When it rains, the floods. In the dry season, potable water,]” Kapitan Galanido says. What is more worrisome to them, Burgos Kagawad Gil Quimiguing says, is how the floods have severely affected their main source of livelihood, farming. Based on the reports, the damage to agriculture left by the February floods reached nearly P8 million for the affected barangays in Dapitan City and the municipality of Sibutad. In Burgos, the damage is not just in that one-time, big-time flood. The regular and constant flooding throughout the year has wrought havoc with the planting season. Already, cropping has been failing, and harvest has been reduced to once a year. But Burgos residents seem resigned to their lot. When asked about their immediate need, they simply wish for an evacuation center on a higher terrain, high enough to keep them dry and safe from the floods.

— with Aedrianne Acar, GMA News Research; Alaysa Escandor, GMA Special Assignments Team/RSJ, GMA News