Filtered by: Topstories

News

Group notes hard task of sending children out of pit mines and into schools

By RIE TAKUMI, GMA News

In small mining communities in Masbate, Camarines Norte, and other ore-rich areas, children as young as nine years old stay underwater in mining shafts for hours to mine gold and other minerals, breathing only through the aid of small tubes.

Other children, meanwhile, refine these ores by using mercury, a chemical that damages their nervous system over time and may even lead to their death.

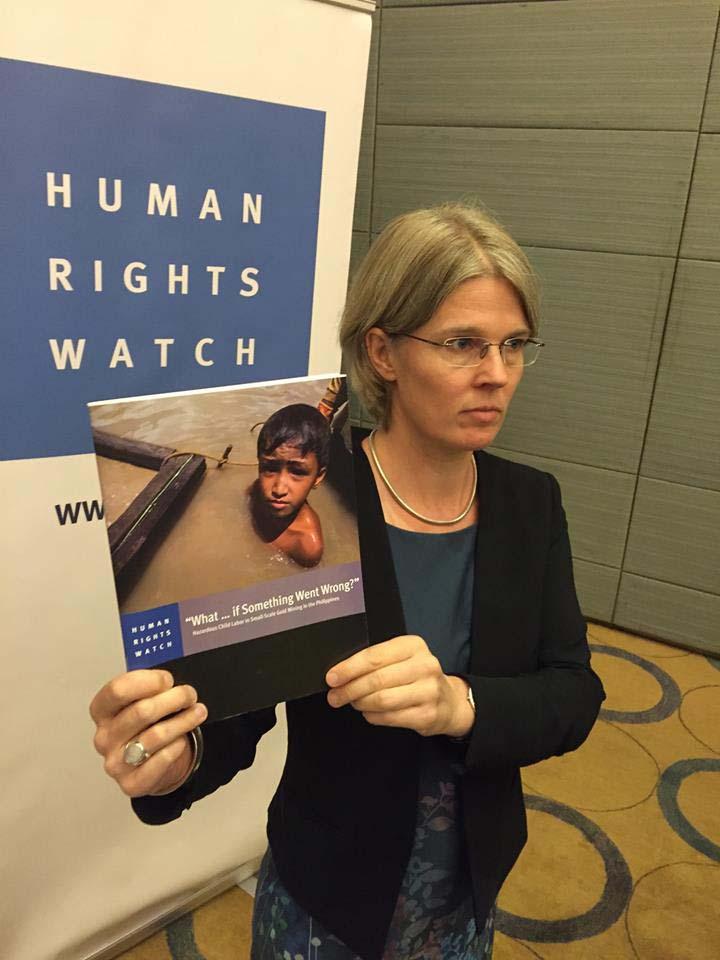

Juliane Kippenberg, associate director of Human Rights Watch's Children's Rights Division. Rie Takumi

"The main cause of this situation is poverty at the house level," said Juliane Kippenberg, HRW Children's Rights Division associate director. "There is no simple, easy answer to this."

She added: "Children from very poor families [who] go into the mines to work there have extremely little chance to break out of that cycle of poverty and get proper education, and get a safer, better-paid job."

Most of the 75,000 child laborers profiled by the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) in mining communities between 2014 and 2015 have parents who also grew up mining for gold. Because of poverty, these parents were forced to allow their children to follow in their footsteps instead of sending them to school.

"A child would need to pay P200 to ride a habal-habal to go to the barangay elementary school. With a very meager income, how can a family support their children?" asked Anna Leah Escresa, executive director of the Ecumenical Institute for Labor Education and Research, Inc. (EILER).

Escresa said one out of five households in these communities had a child working in mining pits, while 84 percent of these homes earned below P5,000.

Jobs for parents, school for kids

Livelihood intervention programs were launched by DOLE to augment the income of poor families and relieve the need to have children work in dangerous circumstances for little money.

The children, meanwhile, are rehabilitated by organizations like EILER through programs like Bata Balik-Eskwela.

Under the program, children are put in transitional schools for five months to assess their capabilities. Graduates are either put into the appropriate grade level or vocational schools.

Out of 337 students who passed through the European Union-backed program, 20 were able to pass the Alternative Learning System (ALS) Accreditation and Equivalency Test while 90 were able to successfully adjust to formal schooling.

Escresa said the number could be higher, but most students are hindered from schooling due to their experiences.

"Grabe rin 'yung adjustments ng mga bata na ilang taon na—two to six years na nagtatrabaho tapos ibabalik sila sa classroom kasi 'yung psyche nila naka-gear na na 'we're earning already'," she said.

Ingrained concern for their parents also swayed students from their studies. To circumvent this, parents send their children to board in EILER's teaching facilities.

"Majority nung aming na-reintegrate sa formal school, we decided to put them in a boarding school. Kasi 'pag nandun sila sa mining communities, 'yung temptation to go back to work would be daily," Escrasa said.

The separation works as most children who transition from their program find coursework easier and understandable in formal schools.

"May confidence na na-build kasi nag-undergo sila ng catch-up lessons. Sabi nila, madaling naintindihan yung mga turo ni teacher kasi na-review na nila dati," Escrasa said.

The HRW interviewed 135 people, including 65 children aged 9 to 17, in Camarines Norte and Masbate from 2014 to 2015 for their field report. —KBK, GMA News

Tags: childminers, humanrightswatch

Find out your candidates' profile

Find the latest news

Find out individual candidate platforms

Choose your candidates and print out your selection.

Voter Demographics

More Videos

Most Popular